Immigration Detention in Malta (2019 Report): Malta’s heavy-handed response to irregular maritime arrivals—including refusing to allow rescue ships to dock and assisting Libyan authorities in intercepting asylum boats—has placed the country at the centre of a bitter EU-wide debate concerning search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean. This restrictive approach is also reflected in its detention policies. Despite having made important changes to its laws, including eliminating mandatory detention provisions, Malta continues to have controversial policies on summary detention and detention without specified time limits. View the Malta Immigration Detention Profile.

________

Introduction to the 2019 Report

The Republic of Malta, an archipelago located in the southern Mediterranean, is the most densely populated country in the European Union (EU). When Malta joined the European Union in 2004 it became the EU’s southernmost border and an important entry point for migrants and asylum seekers attempting to reach Europe. Today, the country has one of highest concentrations of refugees in the world, although the overall number remains comparatively small, totalling approximately 8,000 as of 2017. Until recently, Malta received more than 2,000 irregular boat arrivals annually. This situation led officials to characterise unauthorised migration to the country as an “emergency” and a “national crisis.”

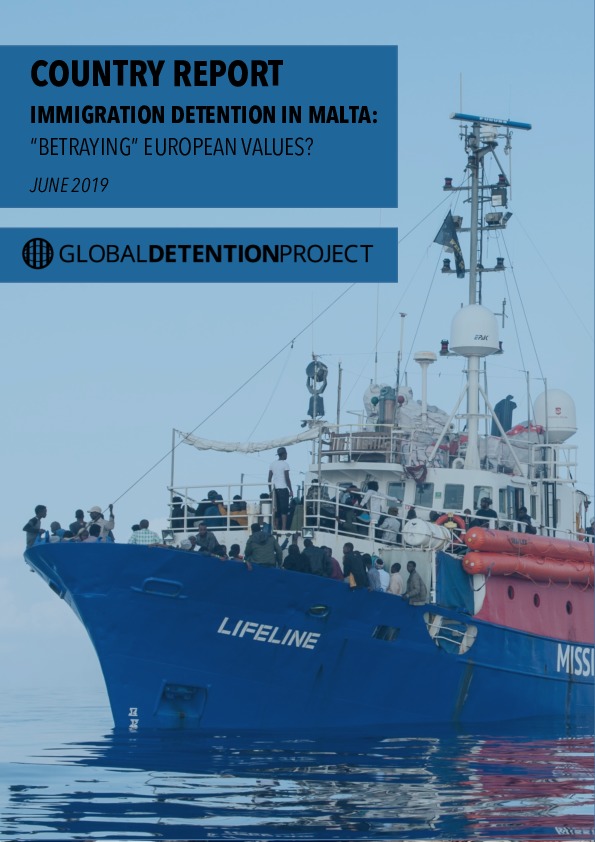

The country is at the centre of a divisive debate in Europe over search and rescue (SAR) missions in the Mediterranean and how to ensure proper care and treatment for migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. In mid-2018, for instance, Malta and Italy repeatedly refused to allow the migrant-rescue ship Aquarius to dock, leaving hundreds of men, women, and children in limbo on the high seas. After one such incident in June 2018, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) accused the two countries of “betraying” European values.

In a separate case that same month, the captain of the charity rescue ship MV Lifeline was charged with operating a ship without proper registration after disembarking 234 people in Malta who had been rescued off Libya. Although the captain was eventually found to have violated registration procedures in a May 2019 ruling, the magistrate in the case denounced the expressions of “racism, intolerance and animosity toward people who are humans like us” that the case had spurred.

A number of more recent events have kept a spotlight on Malta’s heavy-handed response to migrant and refugee arrivals. In May 2019, the captain of the NGO rescue ship More Jonio accused the Maltese air force of assisting Libyan coastguard vessels in intercepting asylum boats located offshore of Malta. Arguing that the asylum seekers would be taken to detention centres in Libya, the captain said: “We denounce this repatriation to an unsafe port, where human rights are not respected.”

Also in May 2019, Malta came under fire from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights for its decision to charge three migrants—two of whom children—with terrorism charges stemming from an incident on a commercial ship carrying 100 rescued people. When the ship announced that it would return the people to Libya, a protest broke out on board, forcing the ship to dock in Malta, where the three teenagers were accused of hijacking the ship. The UN High Commissioner chastised the government for its treatment of the migrants: “In spite of the fact that two of them are minors, all three of the accused were held in the high-security division of an adult prison after they were reportedly interrogated by the authorities without being appointed legal guardians or placed in the care of independent child protection officials.”

In 2015, Malta revised its legal and policy framework regarding the reception of asylum seekers. One critical change was ending the practice of automatically detaining individuals who enter the state irregularly, a practice that had set Malta apart from other EU countries—and brought it more closely in line with Australia and its controversial mandatory detention policies. Today, irregular arrivals are supposed to be transferred to an “Initial Reception Centre,” where immigration officers are to assess on a case-by-case basis whether there are grounds for longer-term detention. However, civil society groups including Jesuit Refugee Services (JRS) and Aditus have argued that in practice, those arriving irregularly often do not pass through the Initial Reception Centre and are instead directly placed in detention.

When Malta took over the presidency of the European Council in January 2017 it listed migration as a key priority. Its agenda included strengthening the common European Asylum system by revising the Dublin regulations and improving implementation of the relocation system. Malta also emphasised the EU objective of completing the work of “the European External Investment Plan to promote sustainable investment in Africa and the Neighbourhood and to tackle the root causes of migration.” Another critical focus was the “wide-ranging cooperation” on Libya, as spelled out in the 2017 “Malta Declaration” of the European Council “addressing the Central Mediterranean route.” Cooperation with Libya has included training and equipping the Libyan coast guard to enhance border management capacity and curtail migration to the EU. These efforts have been the subject of intense scrutiny due to the numerous reports of severe human rights abuses that migrants and asylum seekers face in Libya, including in detention centres.