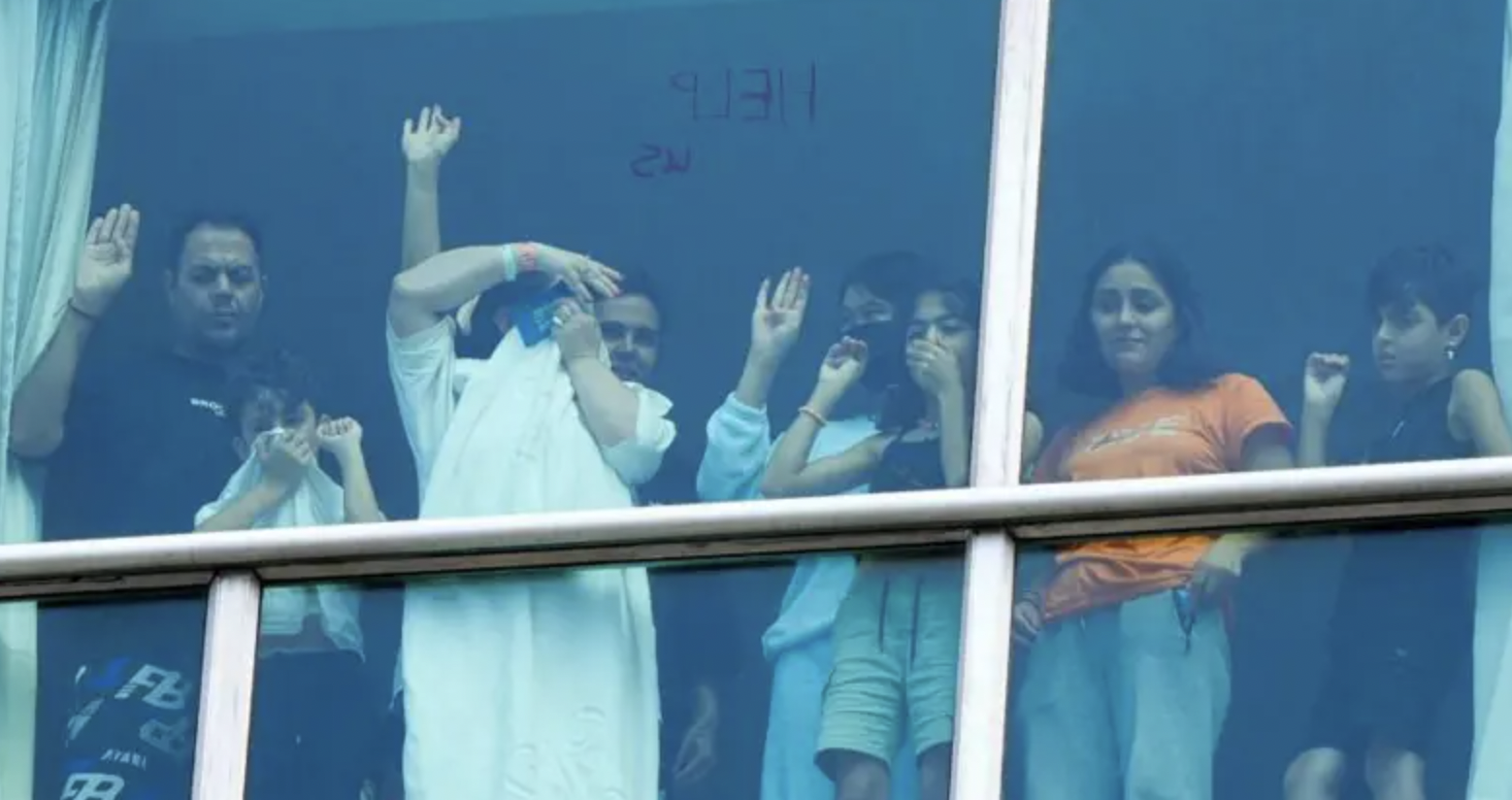

The US has deported hundreds of people to countries like Panama, Costa Rica, and El Salvador as part of the Trump administration’s plan to deport “millions.” On arrival in Panama, deportees have been detained in several ad hoc facilities where reports highlight a serious disregard for fundamental human rights. […]

Panama Plans to Deport Irregular Migrants with Financial Support from the US

Panama’s government is planning to ramp up deportations of migrants who reach the country irregularly through the Darién Gap at the border between Colombia and Panama. The jungle trek is a highly dangerous route which sees hundreds of thousands of migrants, including children, crossing every year, while also making many vulnerable to violence, sexual abuse, […]

Panama: Covid-19 and Detention

Responding to the Global Detention Project’s Covid-19 survey, the director of the Panamanian section of “Fe y Alegria” an NGO part of the Jesuit Migration Network, reported that a moratorium on new immigration detention orders had been established until 8 June 2020, but that no immigration detainees were released and that those who were in […]

Panama: Covid-19 and Detention

As reported previously on this platform (see the 1 June Panama update), Panama has shifted many undocumented migrants to the border with Costa Rica. The two countries have an agreement regarding migrant mobility, but the agreement cannot be enforced as Nicaragua has closed its borders. The director of the immigration authority in Costa Rica, Raquel […]

Panama: Covid-19 and Detention

Responding to the Global Detention Project’s Covid-19 Survey, the UN human rights regional office in Panama (ROCA) reported that Panama has not established a moratorium on new immigration detention orders and that the country is not contemplating the measure. ROCA also explained that no immigration detainees have been released and that there are no “alternatives […]

Last updated: July 2015

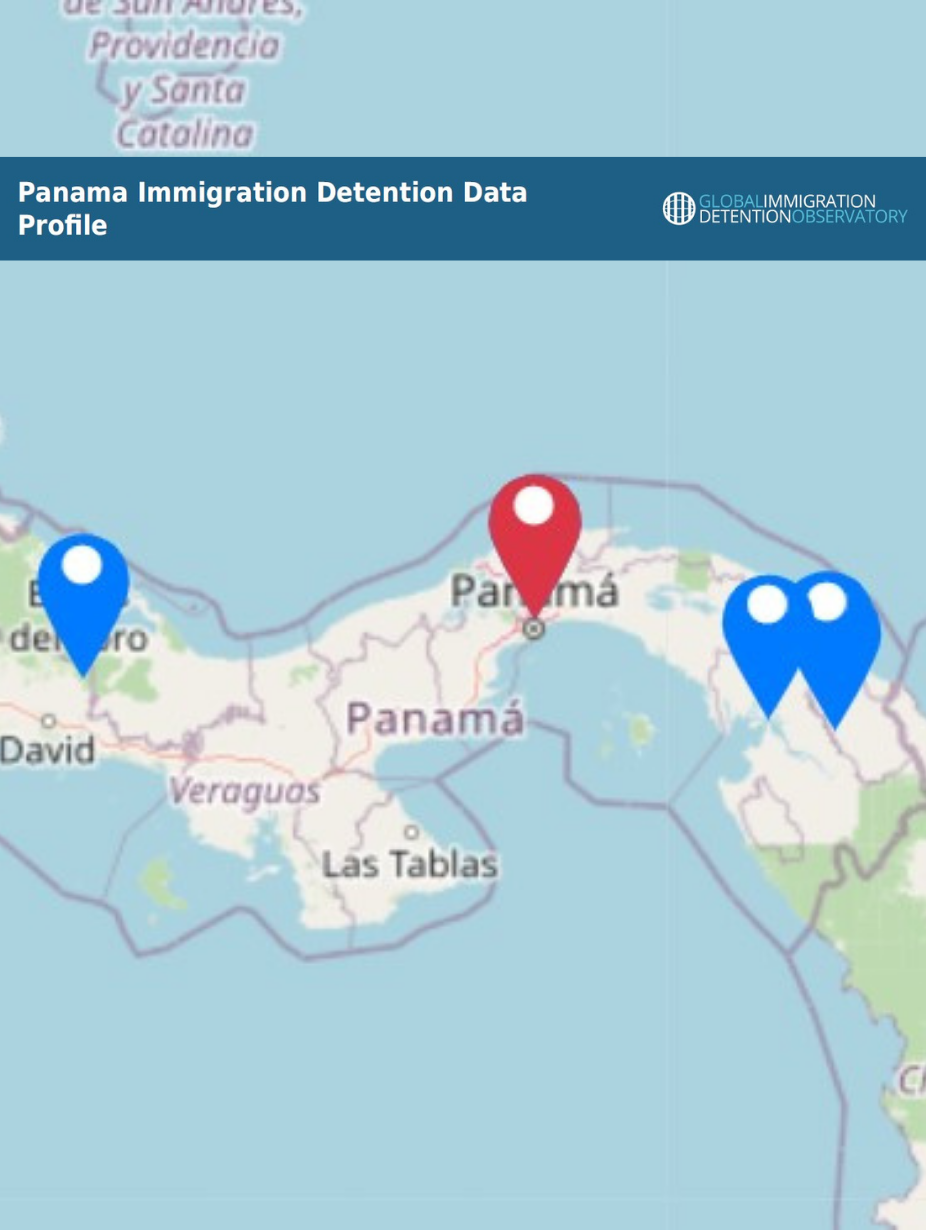

Panama Immigration Detention Profile

Economic growth and geography have helped transform Panama into one of Central America’s most important immigration destination countries as well as a key transit state for people migrating north.[1] In 2013, the country’s migrant population numbered 158,400, or 4.1 percent of the country’s total population. This is four times the average ratio of foreign-born residents in the region.[2] In contrast to other receiving countries in Central America, including Costa Rica and Belize, Panama’s foreign-born population is comprised of people from Latin America and Caribbean countries, as well as various countries in Asia.[3]

In 2008 the country adopted Law Decree No. 3 and Executive Decree No. 320, which overhauled existing migration policy. Law Decree No. 3 establishes the National Migration Service and regulates visas, border control, as well as deportation and detention. Executive Decree No. 320 details the provisions of Law Decree No. 3.

Articles 65 and 66 of Law Decree No. 3 provide that the National Migration Service is to order deportation of any non-citizen who enters the country irregularly; remains undocumented; engages in conduct contrary to good morals; threatens public security, national defence, or public safety; or has served a prison sentence. Before ordering deportation, the National Migration Service is required to issue a detention order. This provision appears to resemble mandatory detention measures observed in other parts of the globe, including Malta. However, the GDP was not able to verify whether detention is systematically applied. Some reports indicate that immigration detention in the country is discretionary.[4] The maximum period of detention is 18 months (Executive Decree No. 320, article 2).

Article 66 of the Law Decree provides that detention orders are to be presented to the person in question. However, according to information provided by the Jesuit Refugees Services-Panama, in practice this information is provided only in Spanish and linguistic assistance is not generally ensured.[5] Immigration detainees have the right to communicate with legal counsel, families, and consulates (Law Decree article 94). The state does not provide legal aid and very few immigration detainees have their own legal counsel. The only legal advice is provided by NGOs (Jesuit Refugees Services and Centro de Asistencia Legal Popular) but due to their limited resources aid is not systematic or sufficient.[6]

There is no judicial review of detention. The Law Decree provides for the possibility for an appeal against deportation. It is an administrative appeal to be addressed to the General Director of the National Migration Service (articles 67 and 96). The only judicial avenue to challenge detention is habeas corpus under the constitution (article 23). However, there are very few appeals because of the lack of a proper information and legal service.[7]

Children are not placed in immigration detention. The Law Decree provides that persons below the age of 18 cannot be detained; they are placed under the responsibility of the Ministry of Social Development (article 93). In practice they are accommodated either with their relatives or in foster homes.[8]

Comprehensive statistics on the number of persons placed in immigration detention do not appear to be available. The only statistics that the GDP is aware of concern people from countries outside Latin America, so-called extracontinentales. According to official statistics, in 2009 317 non-citizens coming from other continents were detained; 503 in 2010; and 147 in 2011. The major countries of origin included China, Bangladesh, Eritrea, Somalia, Nepal, and India.[9]

Panama operates two immigration detention facilities, one for men (Albergue Masculino de Detencion) and another for women (Albergue Femenino de Detencion).[10] Both facilities are run by the National Migration Service and are located in Panama City.

The centre for men is a dedicated immigration detention centre. It has an approximate capacity of 70 but confines on average 130 people at a time. Until 2013 detainees were forced to sleep on mattresses on the floor. The facility has a yard and telephone, which detainees are allowed to use upon request. Following his September 2013 visit, the country’s Ombudsman noted positive changes such as increased visiting time up to one hour and installation of fans and TV. During his visit, 107 persons were detained at the centre.[11]

The centre for women is located inside a police station. It has a capacity of 20 and consists of a single room. The room does not have a window but has air conditioning and a TV. Detainees do not have an access to a yard and no recreational activities are provided.[12]

In 2013, the Inter-American Court on Human Rights issued a resolution on Panama’s compliance with the court’s 2010 judgement in the case of Vélez Loor. In that landmark case Panama was found to have violated several rights of the petitioner, an undocumented migrant from Ecuador. In its 2013 resolution the court found that the country failed to explain what happens to people detained outside of Panama City.[13] In fact, persons apprehended in the border areas (such as province of Darién) are detained in provisional facilities during some days before being transferred to centres in Panama City.[14]

One of the aspects of the Panama’s migration policy addressed in the Velez Loor was criminalisation of migration related offences. Panama's previous migration law (article 678 of the 1960 Law Decree No. 16) provided for prison sentences of up to 2 years for irregular re-entry. The Court ruled that criminalization of irregular entry went beyond the states’ legitimate interest in controlling irregular migration and that detention for non-compliance with migration laws should never involve punitive purposes. According to the Court, a punitive measure applied to a migrant who has re-entered the country in an irregular manner subsequent to a deportation order was not compatible with the American Convention on Human Rights. In particular, the Court ruled that article 67 did not pursue a legitimate purpose and was disproportionate, given that it established a punitive penalty for foreigners who evade previous orders for deportation and, therefore, resulted in arbitrary detentions.[15]

With the new 2008 law, which was adopted before the ruling in Velez Loor was rendered, Panama decriminalized unauthorized entry and re-entry. A similar legal trend can be observed in other countries in various regions, such as Hungary, Malta and Mexico.

[1] International Organization for Migration (IOM). Website. “Missions of the Region: Panama.” http://costarica.iom.int/en/panama/mission_more_information/ (24 June 2015).

[2] UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). International Migration 2013 Wall Chart. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/migration/migration-wallchart-2013.shtml

[3] O’Neil, Kevin, Kimberly Hamilton, and Demetrios Papademetriou (Migration Policy Institute). Migration in the Americas. September 2005. https://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/site/myjahiasite/shared/shared/mainsite/policy_and_research/gcim/rs/RS1.pdf

[4] International Detention Coalition (IDC). 2014. INFORME REGIONAL DETENCIÓN MIGRATORIA Y ALTERNATIVAS A LA DETENCIÓN EN LAS AMÉRICAS. October 2014.

[5] Appel, Carolina (Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados Panama). Global Detention Project Questionnaire. January 2014.

[6] Appel, Carolina (Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados Panama). Global Detention Project Questionnaire. January 2014.

[7] Appel, Carolina (Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados Panama). Global Detention Project Questionnaire. January 2014.

[8] Appel, Carolina (Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados Panama). Global Detention Project Questionnaire. January 2014.

[9] Servicio Nacional de Migración. Flujo Migratorio de Extracontinentales tránsito por las Américas. 2012. scm.oas.org/pdfs/2012/CP28856T.ppt

[10] Appel, Carolina (Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados Panama). Global Detention Project Questionnaire. January 2014. International Detention Coalition (IDC). 2014. INFORME REGIONAL DETENCIÓN MIGRATORIA Y ALTERNATIVAS A LA DETENCIÓN EN LAS AMÉRICAS. October 2014.

[11] Federacion Iberoamericana del Ombudsman. PANAMÁ: Defensoría del Pueblo inspecciona albergue masculino del Servicio Nacional de Migración. 2013. http://www.portalfio.org/inicio/noticias/item/13082-panam%C3%A1-defensor%C3%ADa-del-pueblo-inspecciona-albergue-masculino-del-servicio-nacional-de-migraci%C3%B3n.html

[12] Appel, Carolina (Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados Panama). Global Detention Project Questionnaire. January 2014.

[13] Inter-American Court on Human Rights. RESOLUCIÓN DE LA CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS DE 13 DE FEBRERO DE 2013; CASO VÉLEZ LOOR VS. PANAMÁ SUPERVISIÓN DE CUMPLIMIENTO DE SENTENCIA. 2013. http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/supervisiones/Velez_13_02_13.pdf

[14] Appel, Carolina (Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados Panama). Global Detention Project Questionnaire. January 2014.

[15] INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS. VÉLEZ LOOR v. PANAMA. 23 NOVEMBER 2010. http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_218_ing.pdf. Para. 167, 169, 171, and 172.

DETENTION STATISTICS

DETAINEE DATA

DETENTION CAPACITY

ALTERNATIVES TO DETENTION

ADDITIONAL ENFORCEMENT DATA

PRISON DATA

POPULATION DATA

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DATA & POLLS

LEGAL & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

Does the Country Have Specific Laws that Provide for Migration-Related Detention?

GROUNDS FOR DETENTION

Immigration-Status-Related Grounds

Non-Immigration-Status-Related Grounds in Immigration Legislation

Has the Country Decriminalised Immigration-Related Violations?

Children & Other Vulnerable Groups

DETENTION INSTITUTIONS

Custodial Authorities

PROCEDURAL STANDARDS & SAFEGUARDS

Procedural Standards

COSTS & OUTSOURCING

COVID-19 DATA

TRANSPARENCY

MONITORING

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MONITORING BODIES

NATIONAL PREVENTIVE MECHANISMS (OPTIONAL PROTOCOL TO UN CONVENTION AGAINST TORTURE)

NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS (NGOS)

GOVERNMENTAL MONITORING BODIES

INTERNATIONAL DETENTION MONITORING

INTERNATIONAL TREATIES & TREATY BODIES

International Treaties Ratified

Ratio of relevant international treaties ratified

Individual Complaints Procedures

Relevant Recommendations or Observations Issued by Treaty Bodies

(a) Adopt the protection measures necessary to safeguard the life and ensure

the safety of migrants crossing the Darién Gap and to effectively prevent and combat

all forms of violence against them;

(b) Step up its efforts to investigate allegations of murders, disappearances,

kidnappings, sexual violence, trafficking, assaults, robberies, intimidation and threats

against migrants; prosecute and punish those responsible; and provide comprehensive

reparation to victims and their families;

(c) Fully respect the human rights of migrants housed in migrant reception

centres, in particular the right not to be deprived of their liberty, and ensure that they

have access to effective remedies against any violation of their rights;

(d) Increase efforts to improve living conditions in migrant reception centres

and ensure access to basic services; and, in this connection, the State party is

encouraged to give effect to the recommendations made in February 2023 by the

Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights;14

(e) Ensure in practice the protection of persons seeking asylum or refugee

status, in accordance with the Covenant and international standards, and strengthen

the capacity of the National Office of Refugee Affairs by providing it with sufficient

financial and human resources so that it can process applications for refugee status in

a timely manner.

(a) Ensure the effective participation of migrant, asylum-seeking and refugee children in all decisions that concern them;

(b) Take all necessary measures to avoid immigration detention of children and guarantee that the best interests of the child are taken as a primary consideration in immigration law, in the planning, implementation and assessment of migration policies, and in decision-making in individual cases, in particular with respect to non-refoulement obligations;

(c) Expedite the adoption and implementation of protocols establishing a child-sensitive inter-institutional refugee status determination procedure which includes specific safeguards for unaccompanied asylum-seeking and refugee children, especially in border areas;

(d)Take measures to ensure that asylum-seeking and refugee children have access to education, in line with article 91 of the Constitution of the State party, including by granting them access to the Beca Universal;

(e) Develop campaigns to counter hate speech against asylum seekers and refugees, particularly children."...

> UN Special Procedures

> UN Universal Periodic Review

Relevant Recommendations or Observations from the UN Universal Periodic Review

REGIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MECHANISMS

Regional Legal Instruments

HEALTH CARE PROVISION

HEALTH IMPACTS

COVID-19

Country Updates

Government Agencies

National Service of Migration: http://www.migracion.gob.pa/

Ombudsman: http://www.defensoriadelpueblo.gob.pa/

Directorate General of the Penitentiary System: http://www.sistemapenitenciario.gob.pa/

International Organisations

UNHCR Panama Country Profile: http://www.unhcr.org/panama.html

IOM Panama Country Profile: https://www.iom.int/countries/panama

NGO & Research Institutions