In October, the European Commission opened asylum-related infringement procedures against Hungary. According to ECRE, this is the fifth time such a procedure has been opened against the country since 2015. In a letter of formal notice, the commission says that new asylum procedures that were introduced in response to the coronavirus pandemic are in breach […]

Hungary: Covid-19 and Detention

Following the CJEU’s ruling on 14 May, (see our 15 April update on Hungary) in which the Court held that Hungary had been illegally detaining asylum-seekers as “the placing of asylum seekers or third-country nationals… in the Rözke transit zone… must be classified as ‘detention,’” the government announced it will be closing transit zone camps. […]

Hungary: Covid-19 and Detention

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled on 14 May that “the placing of asylum seekers or third-country nationals who are the subject of a return decision in the Rözke transit zone at the Serbian-Hungarian border must be classified as ‘detention’.” The Court came to that conclusion as “the conditions prevailing in […]

Hungary: Covid-19 and Detention

Among the initial cases of confirmed Covid-19 infections in Hungary were a group of Iranian students studying in Budapest. This spurred Hungarian authorities to capiltiaze on the pandemic to stoke xenophobia, blaming migrants and refugees for the spread of the virus. Prime Minister Viktor Orban said there was a “clear link” between illegal immigration and […]

Last updated: June 2020

Hungary Immigration Detention Profile

- Key Findings

- Introduction

- Laws, Policies, Practices

- Detention Infrastructure

- PDF Version of 2020 Profile

- PDF Version of 2016 Profile

- PDF Version of 2014 Profile

KEY FINDINGS

- Hungarian legislation provides that asylum seekers must stay in designated “transit zones” for the duration of their asylum procedures.

- In May 2020, the European Court of Justice ruled that Hungary was unlawfully detaining asylum seekers at transit sites located on the border with Serbia, prompting the country to close these sites.

- After the closure of the transit sites, Hungary announced that it would only accept asylum applications submitted at its consulates in neighbouring countries, a move that observers said effectively ended asylum procedures in the country.

- Unauthorised entry into Hungary can be subject to criminal prosecution and individuals face up to three years’ imprisonment.

- Hungarian law allows for the detention of families with children and 2017 amendments to the Asylum Act provided for the confinement of unaccompanied children over the age of 14 in transit zones.

- Human rights advocates say that courts systematically fail to conduct individualised assessments of the necessity and proportionality of detention.

1. INTRODUCTION

An important country of transit for migrants and refugees attempting to reach western Europe, Hungary experienced significant increases in arrivals during the 2015 “refugee crisis.” Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has made anti-migrant hostility a hallmark of his administration,[1] spurring the country to become increasingly antipathetic towards asylum seekers and making it a leading bastion of European xenophobia.[2] In the wake of the “refugee crisis,” the country adopted a number of controversial laws and policies, including the construction of fences along its borders with Serbia and Croatia. However, despite the number of arrivals dropping, the “state of crisis” which was declared in 2016 due to “mass immigration” has remained in effect.[3] In March 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic began to accelerate, the government extended the crisis situation for the eighth time since 2015.[4]

In 2015, authorities amended the country’s asylum laws and Criminal Code, punishing unauthorised entry with lengthy prison sentences.[5] Border agents began forcibly pushing people back across the border, at times using tear gas and water cannons to block their entry.[6] While paramilitary groups began to privately patrol border areas,[7] the government also recruited thousands of private individuals to join the police and armed forces in patrolling the borders.[8] The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights vocally criticised such measures, stating that they were “incompatible with the human rights commitments binding on Hungary … and is an entirely unacceptable infringement of the human rights of refugees and migrants. Seeking asylum is not a crime, and neither is entering a country irregularly.”[9]

The government has also undertaken controversial campaigns aimed at influencing public perceptions. In 2015, it sponsored a nationwide billboard campaign promoting slogans such as “If you come to Hungary, you mustn’t take work away from the Hungarians!” However, these were written in Hungarian, indicating that the campaign targeted the Hungarian public rather than non-citizens.[10] The following year, the government spent some 16 million EUR on a campaign to persuade voters to reject EU migrant quotas in a referendum.[11]

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), detention has become “a key element in the Government’s policy of deterrence.” According to the refugee agency, “The Hungarian government uses administrative detention as a deterrent for irregular migrants as well as for those who try to leave Hungary without waiting for the outcome of the asylum procedure.”[12]

Between 2013 and 2015, the number of apprehensions skyrocketed, from 8,255 to 424,055.[13] Until recently, asylum seekers were de facto detained in border “transit zones” with almost no procedural safeguards. Hungarian authorities, however, rejected that people were detained at these sites, saying that they were free to walk back across the border, even as a growing body of evidence indicated otherwise. In 2018, the country blocked the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention from visiting the sites, which they had determined met conditions to be considered sites of deprivation of liberty.[14] Then, in May 2020, the European Court of Justice (ECJ), in a case involving the detention of two Iranian and two Afghan nationals, ruled that the individuals should be released as the conditions of their confinement amounted “to a deprivation of liberty because the persons concerned cannot lawfully leave that zone of their own free will in any direction whatsoever.”[15] The case, which was brought by the crusading NGO the Hungarian Helsinki Society (HHC) on behalf of the detainees, spurred the country to close its transit zones[16]—a move that the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants called “an important step to advance the protection of the human rights of all migrants, especially asylum seekers.”[17]

The country’s detention and asylum practices have resulted in numerous other legal challenges. In a series of rulings, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) found that the country’s immigration detention practices violated Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). In April 2020, the European Court of Justice also ruled that Hungary—as well as the Czech Republic and Poland—had breached their obligations under EU law by shirking responsibility to accept refugees as part of mandatory EU relocation quotas.[18] Hungary—like Poland—had refused to take a single refugee.

The ECtHR has also granted interim measures in various cases concerning the denial of food to rejected asylum seekers detained in transit zones.[19] "The deliberate starvation of detained persons is an unprecedented human rights violation in 21st Century Europe,” stated the Hungarian Helsinki Committee. With the entry into force of amendments to the criminal code, NGOs and individuals who assist asylum seekers during the process of applying for international protection can be prosecuted and face up to one year of prison. A so-called Stop-Soros law criminalised provision of aid to refugees and asylum seekers.[20]

Hungary effectively suspended access to asylum procedures during the Covid-19 crisis when it banned new entries into transit zones.[21] Citing fears that Iranian asylum seekers would bring the virus into the facilities, authorities prevented anyone from entering. Even before this crisis however, Hungary had severely limited the numbers allowed in. Upon opening, authorities were able to register 100 applicants per day in each zone, but steadily this number was arbitrarily reduced until, by January 2018, just one person per zone was permitted entry each day.[22]

In the wake of the May 2020 ECJ ruling, the Hungarian government announced that going forward it would only accept asylum applications submitted outside the country, at its consulates in neighbouring countries. Observers denounced the move as effectively ending the country’s asylum procedures.[23]

2. LAWS, POLICIES, PRACTICES

2.1 Key norms. Legal norms relevant to immigration-related detention are provided in several sources:

- Act II of 2007 on the Admission and Right of Residence of Third-Country Nationals (Third-Country Nationals Act or TCN Act) (2007. évi II. törvény a harmadik országbeli állampolgárok beutazásáról és tartózkodásáról) and its accompanying Government Decree 114/2007 on the Implementation of Third-Country Nationals Act (TCN) constitute the main pieces of immigration legislation in Hungary.

- Act LXXX of 2007 on Asylum (Asylum Act) (2007. évi LXXX Törvény a menedékjogról), which has been amended several times—most recently in January 2019—as well as in the accompanying Government Decree 301/2007 (Asylum Decree) on the Implementation of the Asylum Act regulate asylum proceedings. Amended several times, both the Third-Country Nationals Act and the Asylum Act provide for the detention of non-citizens.

On 5 July 2016 the Asylum Act and the State Border Act were amended so as to legalise the push back of any irregular migrant apprehended within eight kilometres of the Hungarian border with Croatia or Serbia.

In March 2017, Act XX of 2017 was enforced, amending certain acts in order to tighten border procedures (2017. évi XX. törvény a határőrizeti területen lefolytatott eljárás szigorításával kapcsolatos egyes törvények módosításáról). The Asylum Act was amended by new provisions that apply in a “State of Crisis Caused by Mass Immigration,”—a state that can be declared by a governmental decree.[24] Pursuant to these changes, Hungary’s law now prescribes that asylum seekers must stay in designated areas within a transit zone for the entire duration of their asylum procedures, including the time required to enforce Dublin orders. (On 21 May however, these facilities were ordered to be closed – for more, see 2.5 Asylum seekers.) Despite a drastic decrease in the number of asylum seekers, as of May 2020 the “state of crisis” was still in force. Act XX of 2017 also suspended the eight-kilometre territorial limitation of push-backs, empowering the police to apprehend irregular migrants anywhere in Hungary and to automatically escort them through the border.

On 20 June 2018, Act VI of 2018 (in its draft form known as the “Stop Soros” package) was adopted by Parliament. Not only did this act extend police competence to prevent “unlawful migration” and to cover asylum issues[25] but it also introduced the concept of “inadmissibility” in regards to asylum claims. Specifically, it provides for the automatic rejection of claims filed by individuals who have transited through a country classified as a “safe transit country” in which they were not exposed to persecution or serious harm, or if an adequate level of protection was available.[26] The act also introduced new provisions under the Seventh Amendment to the Fundamental Law of Hungary (the Hungarian Constitution)—with Article XIV(1) now stating that “No alien population shall be settled in Hungary.” It is now also constitutionally established that “any non-Hungarian citizen arriving to the territory of Hungary through a country where he or she was not exposed to persecution or a direct risk of persecution shall not be entitled to asylum.”

Many of these legal amendments have been the subject of fierce criticism. Following its March 2017 visit, the UN Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture stated that it had expressed “serious concerns” to the government “regarding the law recently adopted that would allow Hungary to detain all asylum seekers in closed facilities for an extended period of time. We will make recommendations concerning this in our confidential report to the authorities.”[27] Similarly, in July 2018 the European Commission launched an infringement procedure concerning the new inadmissibility ground. According to the commission, the “non-admissibility ground for asylum applications … is a violation of the EU Asylum Procedures Directive.”[28] In 2018 the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC) also expressed concerns over the negative impact of the major legislative reforms adopted over the past few years. It recommended that the Hungarian government ensure that its legislation and practices related to the treatment of migrants and asylum seekers are brought into line with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[29] In 2019, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights urged the Hungarian government to repeal the decreed “crisis situation” and to bring the country’s asylum legislation in line with its human rights obligations.[30] More recently, in March 2020, the ECJ found the “safe transit country” inadmissibility concept to be incompatible with EU law and held that it cannot be applied.[31]

2.2 Covid-19 response. After the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, authorities sought to link the virus to migration, characterising migrants and asylum seekers as potential virus-carriers. As the Chairman of the Parliamentary Defence Committee stated on 13 March, “There are around 130,000 people stranded on the Balkan route who would like to enter the EU. Most of the migrants are not from Syria but from Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. They are economic migrants coming from unsafe sanitary conditions.”[32] Prime Minister Viktor Orbán meanwhile, was even more explicit, stating that there is a “clear link” between immigration and the virus.[33]

In early March, before any cases had yet been confirmed within the country, authorities banned entry to transit zones.[34] With asylum applicants only able to lodge applications within such zones (see 2.5 Asylum seekers), this move effectively suspended access to asylum procedures. Authorities later justified this move by claiming that new arrivals from Iran would pose a health threat to those already inside. Fuelling this anti-Iranian narrative was the fact that among the initial cases of confirmed Covid-19 infections in the country were a group of Iranian students studying in Budapest. Since then, authorities have taken steps to forcefully expel some of these students, stating that they had violated quarantine measures.[35] However according to the HHC, many of the students slated for expulsion had strictly followed quarantine measures, and authorities had instead issued a blanket decision with no attention paid to the conditions the students may face in Iran.

Hungary also received significant international criticism following its adoption of an emergency law allowing the government to rule by decree indefinitely. On 6 April, the government introduced a new decree on internal and administrative rules applicable during the emergency. According to the decree, a third country national issued with an expulsion order—due to their violating Article 361 of the Criminal Code (violating the rules of epidemic control) or based on an assessment that concludes they pose a risk to national security, public security, or public order—may not apply for immediate legal protection during the administrative proceedings instituted against the decision.[36]

2.3 Grounds for detention. The Third-Country Nationals Act sanctions two types of migration-related detention (őrizet): “alien policing detention,” which is meant to ensure deportation or a transfer based on the EU Dublin Regulation, and “detention prior to expulsion.”[37]

Section 54(1) of the Third-Country Nationals Act provides five grounds for “alien policing detention”: when a non-citizen (1) hides from the authorities or seeks to obstruct the enforcement of an expulsion or transfer order; (2) has refused to leave the country, or is delaying or preventing the enforcement of expulsion (risk of absconding); (3) has seriously or repeatedly violated the code of conduct of the place of compulsory confinement; (4) has failed to report to the authorities as ordered; (5) is released from imprisonment to which they were sentenced for committing a deliberate crime.

Despite these grounds, the HHC has reported that in practice, asylum seekers whose asylum applications have been declared inadmissible and rejected have been placed under the aliens policing procedure and have subsequently remained detained in transit centres until their removal—and it remains unclear under what grounds detention is ordered. Almost every single asylum application which has been lodged since the inadmissibility concept entered into force in July 2018 has been declared inadmissible.[38]

By virtue of Section 55(1) of the Third-Country Nationals Act, “detention prior to expulsion” may be imposed in order to secure the conclusion of pending immigration proceedings if: (1) the non-citizen’s identity or the legal grounds of their residence are not conclusively established; or (2) the person’s return under the bilateral readmission agreement to another EU Member State is pending.

2.4 Criminalisation. In September 2015, Hungary amended its Criminal Code, introducing three new crimes related to crossing the border with Serbia, including: unauthorised entry into the territory “protected by the border closure,” which is punishable by up to three years’ imprisonment; damaging the border closure, which is punishable by up to five years’ imprisonment; and obstructing the construction or maintenance of the border fence, which is punishable by up to three years’ imprisonment.[39] Although the legislation provides that persons convicted for irregular border crossing could serve prison terms, Human Rights Watch (HRW) observed that most of them are instead confined in immigration detention.[40]

If an individual submits an asylum application, criminal procedures are not suspended by the court. According to UNHCR, “This stands at variance with obligations under Article 31 of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, to which Hungary is a State party.”[41] The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) has also expressed concern regarding the pursuance of criminal investigations in cases of irregular border crossings. In particular, the CPT notes that Article 31 of the Refugee Convention stipulates that states should not impose penalties, on account of illegal entry or presence, on refugees coming directly from a territory where their life or freedom was threatened.[42]

Act XX of 2017 amended Section 353/A of the Criminal Code, introducing “supporting and facilitating illegal migration” as a criminal offence. The new provisions criminalise all those who engage in, or provide material resources for, activities that facilitate asylum applications—including the preparation or distribution of information materials, which are, at a later stage, declared inadmissible. Individual offenders may be sentenced with between five and 90 days in prison. However, sentences can be extended to one year if the offence is committed for financial gain, if support is provided to more than one person, or if the offence is committed in the border zone. Associations committing the offence can be fined and even dissolved.[43]

2.5 Asylum seekers. In recent years, amendments to Hungarian legislation have steadily made it harder for asylum seekers to lodge applications for protection. Until the May 2020 ECJ ruling ordering the end of unlawful detention at Hungary’s transit zones, asylum seekers were obliged to submit their asylum applicants while confined at these sites. While the case was an important victory for asylum seekers and NGOs like the Hungarian Helsinki Society that supported detainees, the closure of the facilities immediately raised questions about the future of asylum procedures in the country. Shortly after the ECJ ruling, the government announced that it would only accept asylum applications submitted outside the country, at its consulates in neighbouring countries. Observers denounced the move as effectively ending the country’s asylum procedures,[44] while the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants urged Hungary to “take this opportunity to review its asylum procedures and practices to ensure individuals seeking protection under international human rights and refugee law have access to territory and asylum in Hungary.”[45]

With the July 2013 amendment to the Asylum Act, which partially transposed the EU (Recast) Reception Conditions Directive, Hungary established grounds for detention that were specific to asylum seekers. As in Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, the EU Reception Conditions Directive led to the introduction, or expansion, of the justification for detaining persons seeking international protection.

Under Section 31/A(1) of the Asylum Act, persons seeking international protection can be detained for the following reasons: (a) in order to establish their identity or nationality; (b) if there is a well-founded reason to presume that they are applying for asylum exclusively to delay or frustrate their expulsion; (c) in order to obtain the information necessary for processing the asylum claim, where there are well-founded grounds for presuming that the applicant is delaying or frustrating the asylum procedure or presents a risk of absconding; (d) to protect public order, national security, or public safety, or in the event of serious or repeated violations of the designated place of stay; (e) if the asylum application has been submitted at the airport; or (f) if it is necessary to carry out the Dublin procedure and the applicant poses a serious risk of absconding. These grounds apply only to asylum seekers who have submitted one application. Persons who file subsequent asylum requests are subject to detention on the grounds spelled out in the Third-Country Nationals Act.[46]

Pursuant to Article 31/A(1a), authorities may place a non-citizen in asylum detention if they have not submitted an asylum application but nonetheless qualify for a Dublin transfer.

Observers have highlighted a number of concerns regarding the Asylum Act’s detention-related provisions. In particular, they point to the first ground—verification of the applicant’s identity and nationality—which could be applied in most cases given that more than 95 percent of asylum seekers arrive in Hungary without documents. Moreover, the HHC points out that the detention provisions are vaguely formulated, leaving discretion to the authorities to interpret them broadly, which could lead to a sharp increase in the number of detained asylum seekers.[47] In a similar vein, UNHCR has recommended that the country develop specific criteria for each detention ground that could be used by law enforcement authorities when assessing the necessity of detention.[48]

According to the HHC, the most common ground to be used in Hungary has been the risk of absconding, which is sometimes applied alongside the need to identify the person. Section 36/E of Decree 301/2007 defines a risk of absconding as the non-citizen’s failure to cooperate with authorities, and thus is deemed likely if the person a) refuses to make a statement or sign documents, (b) supplies false information in relation to their personal data, or (c) based on their statements, it is probable that they will leave for an unknown destination and it can thus be reasonably assumed that they will undermine the purpose of asylum proceedings, including Dublin procedures. The HHC reports that assessments are often conducted in an arbitrary manner. For instance, in 2014 the HHC came across detention orders that found persons at risk of absconding because they had stated that their destination was the EU, without explicitly mentioning Hungary.[49]

Both UNHCR[50] and the Council of Europe Human Rights Commissioner[51] have expressed concern regarding Hungary’s failure to individually assess the necessity and proportionality of detention. HHC similarly reports that detention orders are schematic and do not individually assess the necessity and proportionality of detention, while alternatives to detention are not regularly and properly examined (see 2.10 Non-custodial measures (“alternatives to detention”)).[52] Meanwhile, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance has pointed to arbitrariness in detention orders.[53]

Following the 2017 amendments to the Asylum Act, transit zones became the only places where it was possible to apply for asylum. Asylum seekers, including those in a Dublin procedure, could not leave the zones before their procedures were complete. Consequently, almost all asylum seekers were confined in transit zones. While the Hungarian government argued that transit zones were designated “places of accommodation,”–pointing to the fact that no detention orders are issued, and that asylum seekers are free to leave the facility (albeit only if they leave for Serbia)—rights observers including the HHC[54] considered confinement in transit zones as constituting de facto detention. According to the Commission for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, the confinement of asylum seekers in transit zones qualified as detention, given that leaving the transit zone deprived asylum seekers of their right to apply for international protection. The commissioner further argued that the lack of legal basis for this deprivation of liberty raised serious questions on the arbitrary nature of detention.[55]

A non-citizen could only apply for asylum if they were detained in a transit zone, and as the statistics above highlight, the number of persons “allowed” to be detained in transit zones—and thus apply for international protection—has decreased in recent years. While authorities were initially able to process 100 entries a day, by 2016 only 20 to 30 persons were permitted into Hungary's two transit zones each day. By November 2016, this had decreased to 10 persons a day, and in 2017 it further decreased to five persons per day. From 23 January 2018, only one person was allowed into each transit zone per day and during the first 10 days of July 2018, no asylum seekers were allowed into transit zones, thus meaning that no asylum seeker was able to apply for protection.[56] At the start of the Covid-19 crisis, transit zones were effectively sealed off, with no asylum seekers permitted entry (see 2.2 Covid-19).

The National Directorate-General for Aliens Policing (NDGAP) was responsible for deciding who could enter the transit zone each day. Since March 2016, a growing number of migrants and asylum seekers have gathered in “pre-transit zones.” Located partly on Hungarian territory, they are sealed off from the transit zones, and are considered by Hungarian authorities to be in “no man’s land,” seemingly justifying authorities’ refusal to meet the basic needs of those inside.[57]

With the entry into force of the new inadmissibility ground, it has become almost impossible for asylum seekers to obtain protection. Out of all applications lodged between July 2018 and July 2019, the HHC is only aware of three positive decisions.[58] Asylum seekers whose applications have been declared inadmissible, and thus rejected, have been placed under the alien policing procedure and detained in transit zones pending their deportation.[59]

In May 2020 however, after the ECJ ruling, the situation dramatically changed when Hungary announced the closure of its transit zones. Prime Minister Orbán’s Chief of Staff said, “the Hungarian government disagrees with the ruling, we consider it a risk with regard to European security, but as an EU member state, we will adhere to all court rulings.”[60] Non-nationals who had been confined inside were reportedly moved to reception centres inside Hungary while their asylum applications are conducted.

The situation in transit zones had long been subject to considerable scrutiny. In April 2017, following the introduction of mandatory detention for asylum seekers, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi called for a temporary suspension of all Dublin transfers of asylum seekers to Hungary “until the Hungarian authorities bring their practices and policies in line with European and International law.”[61]

In 2018, the HRC expressed concerns over the use of restrictions on personal liberty as a deterrent to unlawful entry and not in response to an individual examination of risk. The committee therefore recommended that Hungary “refrain from automatically removing all asylum applicants to the transit areas, thereby restricting their liberty, and conduct individual assessments of the need to transfer them, on a case-by-case basis.”[62] Similarly, in 2019 the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) recommended that Hungary ensure that the detention of asylum seekers is used only as a measure of last resort.[63]

2.6 Children. Hungarian law allows for the detention of families with children, and following the 2017 amendments to the Asylum Act, unaccompanied children can also be held in transit zones—a fact that has attracted considerable international scrutiny.

Pursuant to the Third-Country Nationals Act and the Asylum Act, families with children can be detained as a measure of last resort for a period of no more than 30 days and shall be provided with separate accommodation that guarantees adequate privacy (Asylum Act, Sections 31/A(7), 31/B(3) and 31/F(1)(b); TCN Act, Sections 56(3) and 61(2)). Minors must be provided with leisure activities, including play and recreation that is appropriate to their age. They must also have access to education either in the detention centre or at an outside institution (TCN Act, Section 61(3)(i)-(j); Government Decree 114/2007, Section 129).

Under both the Third-Country Nationals Act and the Asylum Act, unaccompanied children cannot be detained (Asylum Act, Section 31/B(2); TCN Act, Section 56(2)). Unaccompanied children are transferred to special child protection centres such as those in Fót and Hódmezővásárhely.[64]

However, following the introduction of the 2017 amendments to the Asylum Act, unaccompanied asylum seekers aged 14 and above could be held in transit zones at times of “crisis situations.” (This changed in May 2020, when Hungary announced the closure of its two transit zones, see 2.5 Asylum seekers.) During a visit to the transit zones in October 2017, the CPT found that minors above the age of 14 who were detained were appointed a guardian who was required to attend all stages of their asylum procedure.[65]

According to the information provided by Hungary’s Immigration and Asylum Office (IAO), 91 unaccompanied minors were detained in transit zones in 2017.[66] No child was placed in asylum detention in 2018, but 24 accompanied minors were placed in asylum detention in 2017.[67] According to data collected by UNHCR 190 children were detained in 2015.[68] Meanwhile, according to the HHC, approximately one third of asylum seekers waiting in “pre-transit zones” are children (for more on “pre-transit zones,” see 2.5 Asylum Seekers).[69]

Both HHC and UNHCR have reported that some unaccompanied children have been detained due to inaccurate age assessments. Conducted by police-employed physicians, age assessments are based simply on physical appearance.[70] In 2014 and 2015, UNHCR observed that children with disputed ages were systematically detained and that age-assessment procedures were frequently delayed, leaving them in detention for even longer.[71] During its October 2015 monitoring visit to detention facilities, Human Rights Watch (HRW) heard from nine unaccompanied children who, despite being under the age of 18, had had either no age assessment or only a cursory one.[72] In August 2016 UNHCR observed a new practice, whereby applicants for international protection who disagree with their age as registered in the asylum procedure are required by the Office of Immigration and Nationality (OIN) to cover the costs of a medical age assessment procedure. Due to a lack of sufficient financial resources, many applicants are unable to cover these costs.[73] Following its visit to transit centres in February 2017, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) also expressed concerns regarding the manner in which age assessments were performed. According to the committee, age assessments were performed by military doctors who had no formal training to perform such a task, and were ultimately based on an estimation based on physical appearance.[74]

As the HHC has noted, since the 2017 amendment to the asylum act, age assessments have become even more important given that the law differentiates between unaccompanied children above and below 14—and yet, the margin of error in age assessments tends to be broadest at around 15 years of age. “The military doctor does not possess any specific professional knowledge that would make him appropriate to assess the age of asylum seekers, let alone differentiate between a 14 and 15-year-old.”[75]

Hungary’s detention of children has been the subject of international scrutiny. In 2014 the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recommended that Hungary ensure that unaccompanied asylum seeking and migrant children are not detained “under any circumstances” and that age assessments take into account all aspects, including psychological and environmental, of the person under assessment.[76] That same year, UNHCR recommended that Hungary delete the provisions of the Asylum Act and Third-Country Nationals Act, which permit the detention of families with children. Despite the emphasis of these provisions upon last resort, UNHCR noted that since September 2014, asylum-seeking families with children had been routinely detained in Hungary.[77]

In 2018, the HRC urged Hungary to ensure that unaccompanied and accompanied minors are not detained, except as a measure of last resort, and that the decision should always be made in the best interest of the child.[78] Most recently in early 2020, the CRC noted a plethora of concerns in its concluding observations on Hungary. Amongst these, the Committee noted the detention of children over the age of 14 in transit zones—and the inadequate nutrition provided to them; violence inflicted by border police on children and their families during interception and removal operations; and the fact that children and their families found staying irregularly may be expelled without the possibility of applying for asylum. The committee thus urged Hungary to amend asylum law to prohibit the expulsion of children – and ensure that the law conforms with the Convention, repeal the 2017 amendments to the to the Asylum Act, and conduct training for border police on the rights of the child and of asylum seekers.[79]

2.7 Other vulnerable groups. According to the Asylum Act, persons in need of special treatment include: unaccompanied children, elderly persons, disabled persons, pregnant women, single parents with a minor child, and any person who has suffered torture, rape, or any other form of psychological, physical, or sexual violence. However, while legislation refers to this group of persons, it does not provide any additional guidance and no mechanisms are in place to identity such individuals.[80]

As a result, vulnerable people are regularly detained in Hungary. The country has been repeatedly criticised for these practices and UN bodies have urged authorities to adopt reforms. In October 2015, HRW documented cases in which pregnant women, accompanied and unaccompanied children, and people with disabilities were detained for prolonged periods. Additionally, reports have highlighted that women and families with young children who were accommodated at the Bekescsaba Asylum Detention Facility had to share common facilities—such as the laundry room, dining hall, and courtyard—with unrelated men.[81] In 2018, the Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (GRETA) expressed concerns at the lack of mechanisms in place to identify victims of trafficking. The GRETA delegation found that most staff working in the transit zones could not explain what procedures would be followed or name the competent authorities for decisions on victim identification and referral. The report further noted that “the transit zones themselves do not create an atmosphere of trust, which would make it possible for victims of trafficking to come forward and discuss their situation.”[82] The U.S. State Department’s 2019 Trafficking in Persons report similarly noted the country’s failure to adequately screen for trafficking indicators amongst vulnerable populations.[83]

2.8 Length of detention. The Third-Country Nationals Act provides that non-citizens held on grounds provided for “alien policing detention” can be kept in custody for an initial period of 72 hours. Within 24 hours of arrest, the immigration authority must file a request for extending detention beyond this initial period with the local court. The court may extend detention for consecutive 60-day periods, but for no longer than six months in total (TCN Act, Section 54(4)-(5) and 58(1)-(2)).

Once this six-month period ends, the court may extend aliens policing detention for an additional six months under two circumstances: 1) if the execution of the expulsion order lasts longer than six months because the detainee fails to cooperate with the competent authorities; or 2) if there are delays in obtaining the necessary documentation to carry out a removal due to circumstances attributable to the authorities in the country of origin, or another state with whom a readmission agreement has been established (TCN Act, Section 54(4)-(5)).

Hungary increased the maximum permissible period of detention when transposing the EU Returns Directive. Prior to the amendment of the Third-Country Nationals Act, the maximum limit of “aliens policing detention” was six months.[84]

Non-citizens held in “detention prior to expulsion” may also be initially held in custody for an initial period of 72 hours, which may be extended by the court until the non-national’s identity or the legal grounds of their residence has been conclusively established. The duration of detention prior to expulsion is included in the total duration of detention under the Third-Country Nationals Act (TCN Act, Section 54(7) and 55(3)).

Likewise, the Asylum Act sanctions an initial 72-hour detention period based on the refugee authority’s order. A court can order an additional stay in asylum detention for up to six months (Asylum Act, Section 31/A(6)).

Until 2017, non-citizens could be held in transit zones for up to 28 days.[85] However, the March 2017 amendments to the Asylum Act removed legal limits to detention length and since then, asylum seekers have been detained until their procedure is completed.[86] During a fact-finding mission in June 2017, the Hungarian authorities informed the Council of Europe’s Special Representative of the Secretary General on Migration and Refugees that the average duration of stay was 33 days.[87] The CPT received similar information in October 2017: while asylum seekers’ length of stay varied between a few days and more than six months, the average was 30 days.[88] The average detention duration for unaccompanied children in transit zones amounted to 47 days in 2017.[89] According to information provided to the HHC by the NDGAP, the average length of detention in Röszke transit zone in 2019 was 121 days, while the average length in Tompa was 154 days.[90]

The length of time a person has spent in asylum detention is not counted towards the maximum permissible length of detention permitted under the Third-Country Nationals Act (Section 54(7)).[91] In addition, if a person who was previously detained is placed in immigration proceedings on the basis of new facts, the duration of their previous detention is not counted in the permissible length of their new detention (Third-Country Nationals Act, Section 56(4)).

Non-citizens who are refused entry to Hungary can be held in a designated place located in the border zone for a maximum period of 72 hours. Those who arrive by plane can be held in a designated place at the airport for up to eight days (TCN Act, Section 41(1)(b)).

Under both the Third Country Nationals Act and the Asylum Act families with children can be detained for a maximum period of 30 days (Asylum Act, Section 31/A(7); TCN Act, Section 56(3)).

2.9 Procedural standards. Although some procedural guarantees exist, they are not always adhered to. Moreover, they do not apply to non-citizens held in transit zones given that authorities do not regard such persons as officially detained.

Immigration detention sanctioned under the Third-Country Nationals Act is to be ordered by the issuance of a “formal resolution.” This “resolution,” along with the court’s initial detention decision and decisions extending detention, are to be communicated verbally to the detainee in a language that they can understand (TCN Act, Section 89(2)). Immigration detainees should also be informed of their rights and duties in their native language or another language they can understand (TCN Act, Section 60(1)).

According to the HHC, in practice while detention orders are usually translated orally to detainees, decisions extending detention are rarely communicated in the same way.[92] In 2012, the UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism recommended that authorities ensure that immigration detainees receive the assistance of a competent interpreter.[93]

Detention orders cannot be appealed (Asylum Act, Section 31/C(2); TCN Act, Section 57(2)).[94] The main legal remedy against detention is judicial review. Judicial review of immigration detention takes places in the form of the court’s validation of the initial detention order issued by the immigration or asylum authorities (72 hours after arrest) and then subsequent extensions of detention requested by the authorities every 60 days (Asylum Act, Section 31/A(6); TCN Act, Section 54(4)).[95] The HHC observed that in practice, automatic judicial review of immigration detention is a mere formality. The courts systematically fail to conduct an individualised assessment of the necessity and proportionality of detention.[96] The district courts’ decisions tend to be very brief and lack proper assessment of the factual basis for decisions. Reportedly, courts sometimes issue more than a dozen decisions within a span of 30 minutes. According to a survey conducted by Hungary’s Supreme Court, of the approximately 5,000 decisions issued in 2011 and 2012, only three discontinued detention.[97]

The Third-Country Nationals Act and the Asylum Act provide for a hearing, during which the detainee and the authorities present their evidence in writing and/or verbally. Parties are to be given the opportunity to study the evidence presented. If the detainee is not present but has submitted comments in writing, these will be introduced to the court. Pre-removal detainees should be granted a personal hearing upon request, although in practice this mechanism appears to lack transparency and consistency. With limited access to legal aid, it is difficult for detainees to request an oral hearing. Asylum detainees are also to be granted an obligatory personal hearing during the first extension of detention—that is, during the court’s validation of the initial detention order—while hearings for subsequent extensions must be requested (Asylum Act, Section 31/D(3)-(8); TCN Act, Section 59(3)-(8)).[98] One source in Hungary described the personal hearing as “15 people … brought together in front of a judge who simply confirms their detention orders, without any individual examination.”[99]

Both the WGAD and the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights expressed concern regarding the lack of effective legal remedy against immigration detention and recommended that courts carry out a more effective judicial review of immigration detention.[100] In 2012, the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism recommended that the country ensure that more administrative judges with relevant knowledge of, and competence in, human rights asylum standards are involved in the judicial review process of immigration detention. The rapporteur also recommended that Hungary ensure that specialised human rights training with a particular focus on the principle of non-discrimination and the human rights of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers is provided to members of the judiciary.[101]

In the 2015 case of Nabil and Others v. Hungary, the ECtHR found that immigration detention violated Article 5(1) of the ECHR. The court’s decisions to extend detention did not pay attention to the specific circumstances of the applicants’ situation. The decisions adduced few reasons, if any, to demonstrate the risk of absconding, the alternatives to detention were not explored, and the impact of the asylum procedure was not assessed.[102] In 2012-2013 the court had also found Hungary’s immigration detention practices incompatible with Article 5(1) of the ECHR in cases such as Lokpo and Touré v. Hungary, Abdelhakim v. Hungary, and Said v. Hungary.[103]

Hungarian legislation also provides that the court must appoint a legal representative for immigration detainees who cannot afford to hire one themselves and who do not understand the language. However, the hearing may be conducted in the place of detention and in the absence of the detainee’s legal representative (Asylum Act, Section 31/D(3)-(6); TCN Act, Section 59(3)-(6)). Moreover, according to the HHC, officially appointed lawyers usually offer ineffective legal assistance to immigration detainees, often failing to meet the detainee ahead of the hearing, inadequately studying case files, and neglecting to issue objections to detention order extensions (HHC 2014). Following its 2013 visit to Hungary, the WGAD stressed that “[effective] legal assistance for [immigration detainees] must be made available,” noting that it was mostly civil society lawyers, rather than the ones officially assigned by the state, who provide free legal aid.[104]

Besides automatic review, asylum seekers are entitled to submit an objection to their detention order (Asylum Act, Section 31/C(3)). However, the relevance of this legal avenue is limited in practice. Indeed, non-citizens may only object to the initial detention order, and they have just three days to submit their objection—during which time they do not have access to state provided legal representation.[105]

Under the Act on Administrative Proceedings, immigration detainees, like all other persons, are entitled to compensation for damages caused by administrative authorities. A claim for compensation for unlawful detention is to be made as a civil proceeding against the relevant authority in court. However, there have reportedly been few civil proceedings for compensation for unlawful immigration.[106]

It is important to note that the existing procedural guarantees for asylum and immigration detention did not apply for non-citizens held in transit zones. Indeed, since individuals in transit zones were not considered to be officially detained, no legal remedy to challenge detention existed. According to the HHC, the only way to challenge the decision of placement in a transit zone was through a judicial review against the subsequent decision on an asylum application. However, the HHC considered that this was not effective for several reasons, including the fact that those who receive a positive decision were released, and persons could not complain about conditions in the transit zones when they were no longer detained there. Even in cases in which the court has reviewed the decision to place an individual in a transit zone, judges did not consider the compliance of these decisions under the Reception Conditions Directive. Moreover, the lack of reformatory power of the court coupled with the non-compliance of the immigration and asylum authority with the rulings made this channel ineffective in challenging placement in transit zones.[107]

The lack of procedural safeguards for those in transit zones was highlighted and criticised by various bodies and observers. In Ilias and Ahmed v. Hungary, the ECtHR found that the placement of the applicants in Röszke transit zone amounted to de facto detention, which was unlawful because of the lack of possibilities to challenge such a decision.

In 2018, the HRC expressed concerns regarding the absence of legal requirements to examine each individual’s specific conditions as well as regarding the lack of procedural safeguards allowing detainees to meaningfully challenge placement in a transit area. Further, the committee urged Hungary to provide a meaningful right to appeal against detention and other restrictions on movement.[108] Similarly, in 2019 the CERD expressed concerns over the lack of sufficient legal safeguards allowing asylum seekers to challenge their removal to transit zones.[109]

2.10 Non-custodial measures (“alternatives to detention”). The Third Country Nationals Act provides three non-custodial options: 1) the seizure of travel documents, 2) compulsory residence (which cannot be a community shelter or reception centre), and 3) regular reporting. The scope of their application is limited because the measures only apply to persons in “alien policing detention.” Moreover, only persons whose alien policing detention is based on grounds set up in the Returns Directive—obstructing removal or risk of absconding—can benefit from these “alternatives to detention” (TCN Act, Sections 54(2), 48(2) and 62(1)-(2)).

The Asylum Act provides three alternative measures to asylum detention: 1) periodic reporting, 2) staying in a designated place (including apartments, reception centres, community shelters, or administrative areas), and 3) bail (Sections 2(la)-(lc), 31/A(4) and 31/H). In 2016, UNHCR observed that in practice only the reporting requirements and release on bail had been used since 2014.[110] On the other hand, according to a 2015 HHC report,[111] the application of bail is only rarely used in practice. Provisions relating to the application of bail are poorly defined. It can vary between 500 and 5,000 EUR, but the conditions of assessment are not clearly defined in law. On average, the amount of bail ordered as of December 2018 was 1,000 EUR.[112]

According to the HHC, alternative measures have often not been fully considered by authorities and its accounting of them can be misleading.[113]

While Hungarian law provides for asylum detention to be applied only if no less coercive means can achieve its purpose, in practice decisions lack both individualised assessments and justifications as to why alternatives are not applied.[114] Thus, in 2018 the HRC urged Hungary to expand the use of alternatives to detention for asylum seekers.[115]

Earlier, in 2013, the HHC observed that in general authorities rarely considered alternatives to detention and detention orders did not address whether alternatives had been considered in each case.[116] After its 2013 visit to Hungary, the WGAD urged “the Government to seriously consider using alternatives to detention, both in the criminal justice system and in relation to asylum seekers and migrants in irregular situations.”[117] According to official statistics, of all immigration detainees, two percent were granted alternatives to detention in 2014 and 10 percent in 2015.[118]

In the Interior Ministry’s view, non-citizens are extremely likely to abscond and detention alternatives are not sufficient to ensure that they do not abscond between reporting appointments. Detention is thus more effective in ensuring forced return and preventing absconding.[119]

In 2016, however, the country officially reported that 54,898 persons were granted alternatives to asylum detention while some 2,621 applicants were detained. But according to civil society groups in Hungary, this is deeply misleading because it implies that all asylum seekers who were not detained at that time were in some form of ATD, which is not correct.[120]

In 2017, 1,176 persons were granted alternatives to detention and 391 persons were placed in asylum detention. In 2018, seven people were granted alternatives and seven were placed in asylum detention. Considering that the majority of asylum seekers are de facto detained in transit zones, and that for this kind of detention no less coercive means are prescribed in law, alternatives have been seldom applied in recent years.[121]

2.11 Detaining authorities and institutions. In July 2019 the Government Decree came into force establishing a National Directorate - General for Alien Policing (Országos Idegenrendészeti Főigazgatóság - NDGAP) under police management, which replaced the Immigration and Asylum Office (IAO). This new organisation is in charge of all matters relating to asylum and immigration.[122]

2.12 Regulation of detention conditions and regimes. According to the Asylum Act, asylum detention is to be conducted in detention centres designated for such a purpose (Section 31/A(10)). Pursuant to the Third-Country Nationals Act, “hostels of restricted access” may not be installed in police detention facilities or in penal institutions (Government Decree 114/2007, Section 129(2)). This rule can be deviated from in emergency situations addressed in Section 61/A, when exceptionally large numbers of non-citizens place a heavy burden on the capacity of detention facilities.

The Third-Country Nationals Act (Section 61(2)-(3)) and Asylum Act (Section 31/F) establish that men and women are to be accommodated separately. Detainees have the right to food as well as emergency and basic medical care; may wear their own clothing; can consult their legal representatives and consular personnel; may be visited by relatives; may send and receive packages and letters; can practice religion; may lodge complaints; and may have at least one hour of outdoor exercise a day. Government Decree 114/2007 (TCN Decree) provides that living quarters should have at least 15 cubic metres of space (and five square metres of floor space) per person (or eight square metres per person in family rooms); detention centres shall have a common area for dining and recreation; separate toilets and washrooms—with hot and cold water—for men and women; there must be a nurse to provide basic medical care; facilities must have space for outdoor activities; and premises should have sufficient lighting and ventilation, as well as room for receiving visits and telephone calls (Section 129(1)). Immigration detainees have the right to file complaints about the conditions of their detention. Any complaint lodged verbally or in writing to the authority ordering or carrying out detention must be forwarded without delay to the competent local court. The court must respond to the complaint within eight days (TCN Act, Section 57(3)-(6); Government Decree 114/2007 (TCN Decree), Section 127).

The Asylum Decree similarly provides that detainees should each enjoy 15 cubic metres of space (and five squared metres of floor space)—although this requirement changes in cases of families or couples detained together. Detained applicants should also enjoy an open-door regime, have the option to spend time outdoors, make phone calls, and use the internet. They should also have access to recreational activities. Articles 36/A to 36/F of the Asylum Decree regulate asylum detention and facility requirements.

2.13 Domestic monitoring. Hungary ratified the UN Convention against Torture and its Optional Protocol (OPCAT) in January 2012 and designated the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights (Hungary’s ombudsman institution) as National Preventive Mechanism (NPM).[123] However, according to the information provided by the ombudsman’s website, no visits have been made to places of immigration detention since before 2015.[124]

For more than 20 years the HHC significantly complemented the monitoring work carried out by the NPM. Between 2015 and October 2017, the HHC carried out six monitoring visits to immigration detention facilities and 21 visits to asylum detention facilities. However, in 2017 Hungarian authorities terminated agreements of cooperation with the HHC. The HHC was thus stripped of permission to visit places of immigration and asylum detention.[125]

2.14 International monitoring. Hungary has sought to limit monitoring of many of its detention practices, including preventing NGOs from making visit to detention centres and blocking access by international monitoring bodies to some sites. Nevertheless, its laws and policies have been repeatedly scrutinised and criticised by authoritative rights agencies.

The CERD,[126] CRC, and HRC[127] have expressed concerns regarding numerous issues relating to the situation of asylum seekers, migrants, and refugees, including issues relating to detention.

Having ratified the OPCAT, the UN Subcommittee on the Prevention of Torture (SPT) can monitor places of detention. The SPT carried out a visit in March 2017 focusing on the functioning of the NPM. Recommendations were made regarding cooperation with civil society organisations, funding, and resources and autonomy.[128]

Hungary has ratified the European Convention on the Prevention of Torture. In this framework it receives monitoring visits from the CPT. In October 2017 the CPT undertook an ad hoc visit to Hungary’s transit zones, following which it expressed numerous concerns and suggested various recommendations.[129]

In November 2018, the WGAD suspended its visit to Hungary when it was denied access to Röszke and Tompa transit zones.[130]

2.15 Trends and statistics. Hungary faced considerable migratory pressures during the height of the “refugee crisis,” with border apprehensions increasing from less than 10,000 in 2013 to 424,055 in 2015. Migratory pressures have fallen considerably since then. For instance, the number of asylum seekers decreased by more than 99 percent from 177,135 in 2015 to 500 in 2019. The country expelled 810 people in 2019; 875 in 2018; 685 in 2017; 780 in 2016; 5,755 in 2015; and 3,440 in 2014.[131] In 2019, Hungary refused entry to 13,570 people; 15,050 people in 2018; 14,010 in 2017; 9,905 in 2016; 11,505 in 2015; and 13,325 in 2014.[132]

In 2019, Hungary detained a total of 473 asylum seekers (40 in asylum detention and 433 in transit zones).[133] However, significant discrepancies appear to exist in reports detailing the numbers to be detained. In 2018 for example, the HHC reported that 565 asylum seekers were detained (seven in asylum detention and 558 in transit zones), however information provided by the IAO reported far lower figures. Specifically: between January and April 2018 only 77 non-citizens were placed in immigration detention: 73 non-citizens were ordered detention by the Aliens Policing Authority and only four by the Asylum Authority.[134]

According to the HHC the total number of immigration detainees in 2017 was 2,953, of which 455 were non-nationals having received a detention order by immigration authorities; 391 were asylum seekers in asylum detention; and 2,107 were asylum seekers held in transit zones.[135] According to the Interior Ministry, the country detained 6,496 non-citizens in 2013; 5,434 in 2012; 5,715 in 2011; 3,509 in 2010; and 1,989 in 2009. According to UNHCR, Hungary detained 8,562 non-citizens in 2015.[136]

According to the Office of Immigration and Nationality (OIN), its Alien Policing Department ordered the detention of 1,545 non-citizens in 2015; 1,280 in 2014; 768 in 2013; 1,424 in 2012; 1,208 in 2011; and 1,397 in 2010. Out of 1,545 non-citizens detained by the Aliens Policing Department in 2015, 452 were from Syria, 271 from Afghanistan, and 245 from Kosovo.[137]

Since the introduction of asylum detention in 2013, the OIN has collected statistics on detained asylum seekers. 2,393 asylum seekers were detained in 2015, 4,829 in 2014, and 1,762 in 2013. In 2015, 622 detained asylum seekers were from Kosovo, 548 from Afghanistan, 261 from Pakistan, and 257 from Syria.[138] Previously, the OIN collected data on the number of persons who applied for asylum from detention. In 2012, 1,266 asylum seekers applied for asylum after being detained; 1,102 in 2011; and 822 in 2010.[139]

3. DETENTION INFRASTRUCTURE

3.1 Summary. At the time of this publication in May 2020, Hungary operated four immigration-related detention facilities. Three of the facilities are pre-removal centres, which are located at Budapest Airport, Győr, and Nyírbátor. The remaining facility, located in Nyírbátor, is an asylum detention centre, which has reportedly remained largely unused.[140] Until May 2020, the country also operated two de facto detention transit zone facilities, located in Röszke and Tompa.

On top of the recent transit zone closures, Hungary also closed three asylum detention facilities in recent years. At the end of December 2015, Debrecen was reportedly shut down, followed by Kiskunhalas, and Békéscsaba. After its closure, Kiskunhalas was transformed into a temporary container camp.[141]

Pre-removal detention under the Third-Country National Act and asylum detention under the Asylum Act are carried out in separate facilities. Until recently, the centres had different management. Immigration detention centres were under the authority of the police, while asylum detention centres were managed by the OIN.[142] However, a government decree that entered into force in 2019 provides that asylum and immigration enforcement are both the purview of the police, which established a new National General Directorate for Immigration.[143]

Although the Interior Ministry has noted that non-citizens cannot be detained in prisons,[144] observers have reported that the provisions in the penal code provide that certain persons charged with irregular entry can be held in administrative immigration detention proceedings (awaiting deportation) yet confined in prisons.[145] Pursuant to Section 61/A(1) of the Third-Country Nationals Act, immigration detention can be carried out in prisons under exceptional conditions if the immigration system of the country is under particular pressure. Large-scale refugee flows in 2015 were thus used as a justification to detain non-citizens in prisons.[146] As of 2016, Hungary had an emergency capacity of 440 in prisons.[147] In 2014, the WGAD recommended that Hungary not detain asylum seekers in penal institutions.[148]

3.2 List of detention facilities. Pre-removal detention centres at Budapest Airport, Győr, and Nyírbátor; Röszke and Tompa transit zones (recently closed); and Nyírbátor asylum detention centre.

3.3 Conditions and regimes in detention centres. Conditions in Hungary’s detention facilities have been subject to intense scrutiny. Advocates have regularly pointed to a variety of problems in the treatment of detainees,

including reports of a lack of protection for vulnerable populations (such as families, trafficking victims, and unaccompanied minors), insufficient facilities and care for the mentally or physically disabled, and the “aggressive behaviour of security guards in all the centres.”[149] Of particular concern have been the conditions inside the now-closed Röszke and Tompa transit zones where, detainees faced conditions deemed unsuitable for prolonged periods

3.3a Immigration and asylum detention centres. According to the HHC, from 2008 to 2013 detainees in most detention facilities (with the exception of Békéscsaba) were confined in conditions akin to maximum security prisons. Except for one hour of outdoor exercise and meal-times, non-citizens were kept in their cells, free movement in the premises was generally not allowed, and there were few community or personal activities.[150]

In 2020, it was reported that open-air access remained guaranteed for just one hour each day.[151]

Connected to Nyírbátor pre-removal detention centre,[152] Nyírbátor asylum detention centre reportedly provides asylum seekers with unlimited access to the open-air during the day. However, the open-air space is problematic because it is covered in sand: a surface that makes certain sports difficult, particularly in rainy or cold conditions. There are no benches or trees to provide shelter. Although detainees can access the internet, there are only a handful of old computers. When asylum detainees are escorted from the facility to court for hearings or other visits (such as to the hospital), they are “handcuffed and escorted on leashes, which are normally used for the accused in criminal proceedings.”[153] On 31 December 2019, the facility was reported to be detaining nine individuals, with a total capacity of 105.[154]

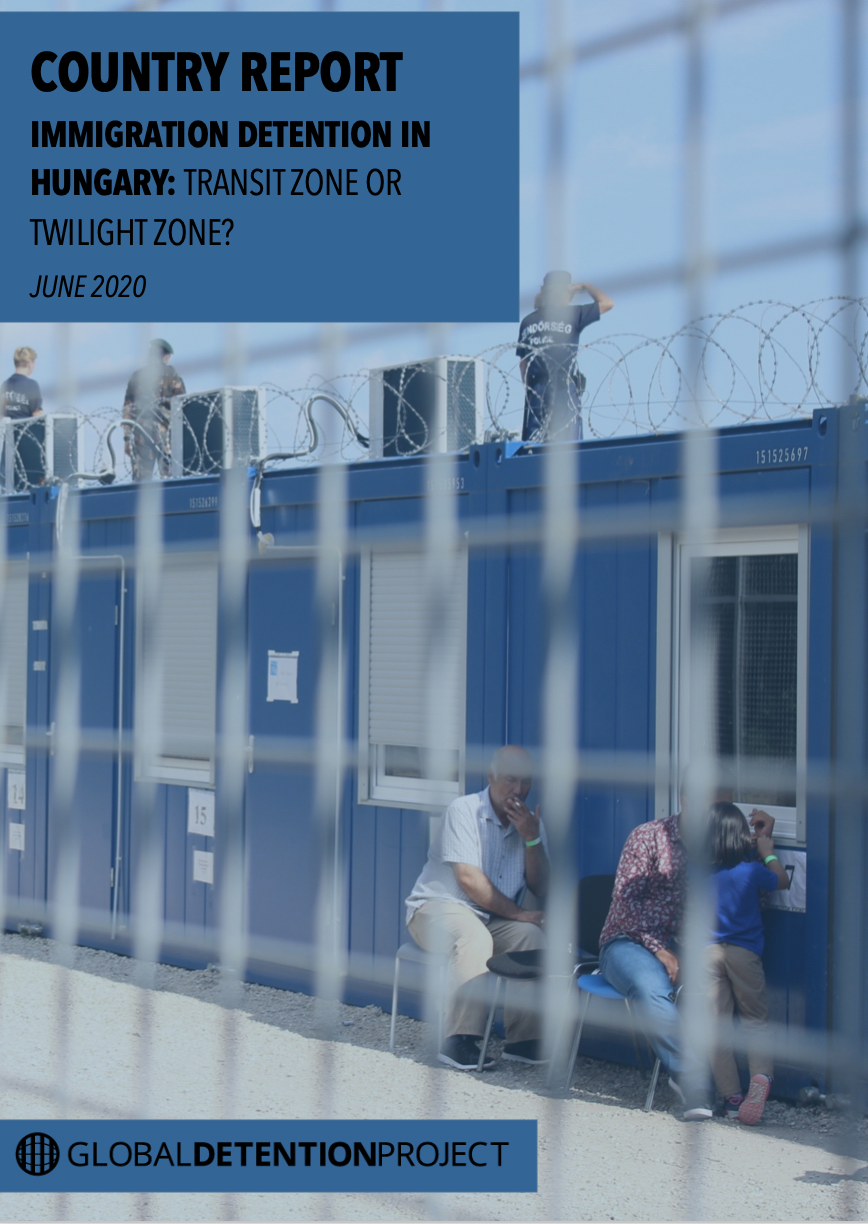

3.3b Transit zones. First established in mid-September 2015, Hungary’s two now-closed transit zones—remotely located and integrated into the country’s border fence—were long the subject of intense criticism. While conditions were reportedly improved following their opening, multiple concerns remained and their closure in May 2020 marked a significant victory for rights activists.

During a visit in October 2017, the CPT noted that the transit zones had been significantly enlarged since their previous visit soon after their opening in 2015, and that while conditions were generally acceptable for a limited period of detention, they were not adequate for prolonged detention.

Foreign nationals were held in rectangular caged areas containing rows of prefabricated accommodation containers. These containers generally measured 13m2 and included two bunk-beds and one bed, as well as five lockers. The committee noted that the accommodation was generally in a good state of repair, had access to natural light and artificial lighting, and included electric heating. As well as accommodation units, the caged areas also included containers serving as an office for social workers, a dining room (featuring chairs, tables, a sink, a fridge, an electric kettle, and a microwave), a laundry room (with a washing machine and tumble dryer), and sanitary facilities.[155]

However, in the CPT’s report, the committee also noted multiple shortcomings. Of particular concern was the carceral nature of both zones, including rolls of razor-blade wire and high wire-mesh fences – not just surrounding the zones, but surrounding the caged accommodation sections. As the committee wrote, “Such an environment cannot be considered adequate for the accommodation of asylum-seekers, even less so where families and children are among them.” (Others, meanwhile, have reported that the facilities were patrolled by police officers and armed security guards, and that with cameras installed in all corners, there was no privacy.) The CPT thus urged Hungarian authorities to revise the design and layout with a view to rendering them less carceral.

In addition, the committee found that conditions inside containers were cramped—despite some units remaining empty, the delegation noted others that were at full capacity. Some detainees also commented on uncomfortable heat in the units during the summer, due to the lack of air-conditioning. The committee also raised concerns that communal outdoor yards did not include shelter apart from a few cloth parasols.

Although foreign nationals could move freely within their sections, had unrestricted access to an outdoor yard and an air-conditioned communal activity room and prayer room, some detainees raised concerns regarding a lack of organised activities. School classes were provided every morning by teachers from the outside community, and some leisure activities were provided by NGOs in the afternoons. This was an important development, as prior to September 2017 no such services were provided. However, the CPT noted that classes were only targeted at kindergarten-age and young school-age children—not for order children. While outdoor yards in accommodation sections for families with children in Röszke included a playground, not of all of Tompa’s outdoor yards featured such equipment.

Others raised similar concerns regarding conditions in transit zones. In 2019, the CERD reported that “the conditions in the transit zones are not adequate for long term stay of individuals, especially women and children,” and noted that detainees face challenges in accessing adequate medical, educational, social and psychological, and legal services.[156] The committee also highlighted reports that food was not provided to failed asylum seekers who remained confined in the transit zones—an issue that Human Rights Watch and others had reported in 2018—and urged authorities to immediately address this.[157] According to the HHC, despite the ECtHR issuing interim measures to provide food, the IAO continued to deny food to some adults.[158]

Following a European Union Court of Justice ruling in May 2020, which held that the confinement of asylum seekers inside the transit zones amounted to illegal detention, Hungary shuttered both facilities (for more, see 2.5 Asylum seekers).

[1] In May 2020, Freedom House noted the failing democratic standards in the country in its “Nations in Transit” report and removed the country’s status as a “semi-consolidated democracy.” Hungary is instead ranked as a “hybrid regime,” placing it alongside states such as Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Ukraine. See: Freedom House, “Nations in Transit 2020: Dropping the Democratic Façade,” 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/05062020_FH_NIT2020_vfinal.pdf

[2] B. Stur, “Hungary MEP Sparks Controversy by Suggesting Pig Heads Could be Used to Deter Refugees,” New Europe, 23 August 2016, https://www.neweurope.eu/article/hungary-mep-sparks-controversy-suggesting-pig-heads-used-deter-refugees/

[3] Hungarian Helsinki Committee (HHC), “One Year After: How Legal Changes Resulted in Blanket Rejections, Refoulement and Systematic Starvation in Detention,” https://www.helsinki.hu/wp-content/uploads/One-year-after-2019.pdf

[4] E. Inotai, “Pandemic-Hit Hungary Harps on About ‘Migrant Crisis,’” Reporting Democracy, 19 March 2020, https://balkaninsight.com/2020/03/19/pandemic-hit-hungary-harps-on-about-migrant-crisis/

[5] M. Pradavi, “How Hungary Systematically Violates European Norms on Refugee Protection,” Social Europe, 31 August 2016, https://www.socialeurope.eu/2016/08/hungary-systematically-violates-european-norms-refugee-protection/

[6] Stuff, “Hungary Turns Water Cannons, Tear Gas on Refugees Breaching Border Fence,” 17 September 2015, http://www.stuff.co.nz/world/europe/72132329/Hungary-turns-water-cannons-tear-gas-on-refugees-breaching-border-fence

[7] Migrant Solidarity Group of Hungary (Migszol), “The Catastrophic Consequences of the 8 km Law and Violence at the Hungarian-Serbian Border,” http://www.migszol.com/blog/the-catastrophic-consequences-of-the-8km-law-and-violence-at-the-hungarian-serbian-border

[8] Human Rights Watch (HRW), “Hungary’s Xenophobic Anti-Migrant Campaign,” 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/09/13/hungarys-xenophobic-anti-migrant-campaign

[9] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “Hungary Violating International Law in Response to Migration Crisis: Zeid,” 2015, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=16449&LangID=E

[10] European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), “Crossing Boundaries: The New Asylum Procedure at the Border and Restrictions to Cccessing Protection in Hungary,” http://www.asylumineurope.org/sites/default/files/resources/crossing_boundaries_october_2015.pdf

[11] Human Rights Watch (HRW), “Hungary’s Xenophobic Anti-Migrant Campaign,” 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/09/13/hungarys-xenophobic-anti-migrant-campaign

[12] UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “UNHCR Global Strategy Beyond Detention: Baseline Reports,” National Action Plan: Hungary, 2015, http://www.unhcr.org/detention.html

[13] Eurostat, “Database: Enforcement of Immigration Legislation,” 2019, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/asylum-and-managed-migration/data/database

[14] Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “UN Human Rights Experts Suspended Hungary Visit After Access Denied,” 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/FR/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23879&LangID=E

[15] Reuters, “EU rules asylum seekers on Hungary border have been 'detained', should be released,” 14 May 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-migration-hungary-ruling/eu-rules-asylum-seekers-on-hungary-border-have-been-detained-should-be-released-idUSKBN22Q2V2

[16] DW, “Hungary to Close Transit Zone Camps for Asylum-Seekers,” 21 May 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/hungary-to-close-transit-zone-camps-for-asylum-seekers/a-53524417

[17] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Closure of “Transit Zones”: an Important Step Forward – Statement by Felipe González Morales, UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants,” 29 May 2020, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25911&LangID=E

[18] Court of Justice of the European Union, “Press Release No 40/20: By Refusing to Comply with the Temporary Mechanism for the Relocation of Applicants for International Protection, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic have Failed to Fulfil their Obligations under European Union Law,” 2 April 2020, https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-04/cp200040en.pdf

[19] Hungarian Helsinki Committee (HHC), “One Year After: How Legal Changes Resulted in Blanket Rejections, Refoulement and Systematic Starvation in Detention,” 2019, https://www.helsinki.hu/wp-content/uploads/One-year-after-2019.pdf

[20] D. Mijatovic, :Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe - Report Following her Visit to Hungary from 4 to 8 February 2019,” 2019, https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=0900001680942f0d

[21] E. Inotai, “Pandemic-Hit Hungary Harps on About ‘Migrant Crisis,’” Reporting Democracy, 19 March 2020, https://balkaninsight.com/2020/03/19/pandemic-hit-hungary-harps-on-about-migrant-crisis/

[22] Heinrich Böll Stiftung, “Deny, Deter, Deprive: The Demolishment of the Asylum System in Hungary,” 19 December 2019, https://cz.boell.org/en/2019/12/19/deny-deter-deprive-demolishment-asylum-system-hungary

[23] Remix, “Hungary effectively ends asylum application process after closing migrant transit zones,” 22 May 2020, https://rmx.news/article/article/hungary-closes-transit-zones-slammed-by-ecj-maintains-strict-border-defense

[24] T. Bocek, “Report of the Fact-Finding Mission by Ambassador Tomáš Boček, Special Representative of the Secretary General on Migration and Refugees to Serbia and Two Transit Zones in Hungary 12–16 June 2017, SG/Inf(2017)33,” 2017, http://bit.ly/2DS9v14; Hungarian Helsinki Committee (HHC), “Country Report: Hungary – 2016 Update,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2017, http://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/hungary

[25] Amendments to Act XXXIV of 1994 of the Police Act in Hungarian Helsinki Committee (HHC), “One Year After: How Legal Changes Resulted in Blanket Rejections, Refoulement and Systematic Starvation in Detention,” 2019, https://www.helsinki.hu/wp-content/uploads/One-year-after-2019.pdf

[26] Amendment to Section 51(2) of the Asylum Act in Hungarian Helsinki Committee (HHC), “One Year After: How Legal Changes Resulted in Blanket Rejections, Refoulement and Systematic Starvation in Detention,” 2019, https://www.helsinki.hu/wp-content/uploads/One-year-after-2019.pdf

[27] Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “UN Torture Prevention Body to Make First Visit to Hungary,” 2017, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21392&LangID=E; Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “Hungary’s Use of Detention in the Spotlight as UN Torture Prevention Body Concludes Visit,” 2017, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21468&LangID=E

[28] European Commission (EC), “Migration and Asylum: Commission Takes Further Steps in Infringement Procedures Against Hungary,” 2018, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-4522_en.htm

[29] UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), “Concluding Observations on the Sixth Periodic Report of Hungary, CCPR/C/HUN/CO/6,” https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2fC%2fHUN%2fCO%2f6&Lang=en

[30] D. Mijatovic, “Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe - Report Following Her Visit to Hungary from 4 to 8 February 2019,” 2019, https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=0900001680942f0d

[31] Hungarian Helsinki Committee, “Asylum Seekers Arriving Through Serbia Cannot be Rejected Automatically,” 24 March 2020, https://www.helsinki.hu/en/asylum-seekers-arriving-through-serbia-cannot-be-rejected-automatically/

[32] E. Inotai, “Pandemic-Hit Hungary Harps on About ‘Migrant Crisis,’” Reporting Democracy, 19 March 2020, https://balkaninsight.com/2020/H03/19/pandemic-hit-hungary-harps-on-about-migrant-crisis/

[33] Hungary Today, “Orbán to EU Counterparts: Clear Link Between Coronavirus and Illegal Migration,” 11 March 2020, https://hungarytoday.hu/orban-to-eu-counterparts-clear-link-between-coronavirus-and-illegal-migration/

[34] E. Inotai, “Pandemic-Hit Hungary Harps on About ‘Migrant Crisis,’” Reporting Democracy, 19 March 2020, https://balkaninsight.com/2020/03/19/pandemic-hit-hungary-harps-on-about-migrant-crisis/

[35] Hungarian Helsinki Committee, “The Rule of Law Quarantined in the Case of the Iranian Student,” 15 April 2020, https://www.helsinki.hu/en/the-rule-of-law-quarantined-in-the-case-of-the-iranian-student/

[36] Hungarian Government, “85/2020. (IV. 5.) Korm. rendelet a veszélyhelyzet során alkalmazandó egyes belügyi és közigazgatási tárgyú szabályokról,” 6 April 2020, https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=A2000085.KOR&dbnum=1