On 7 March, Japan’s cabinet passed a bill amending the country’s immigration and asylum legislation. The bill, which has been slated by rights groups, reinforces the country’s ability to indefinitely detain migrants and asylum seekers. It is now due to be voted on by the country’s parliament. With regards to detention, the amendment bill to […]

Japan: Covid-19 and Detention

Japan’s treatment of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants within its immigration detention estate is again under intense scrutiny after a court ruled that authorities had failed to protect the health of a detainee. The detainee – a 43-year-old Cameroonian asylum seeker – died in detention in 2014. Suffering from diabetes and other health issues, the […]

Japan: Covid-19 and Detention

Japan’s immigration detention system has recently come under renewed scrutiny. In particular, the 6 March death of a 33 year old Sri Lankan woman–Ratnayake Liyanage Wishma Sandamali–who died in the Nagoya Regional Immigration Bureau Detention House following months of health complaints, sparked a wave of criticism and drew international attention. Sandamali had been detained since […]

Japan: Covid-19 and Detention

According to NGO sources, there has been a decrease in arrests and detention orders in Japan during the pandemic. According to the Forum for Refugees Japan (FRJ), the number of detainees had decreased to around 520 by July, compared to 1,054 in April 2020. Additionally, the International Detention Coalition (IDC) reported that 563 asylum seekers […]

Japan: Covid-19 and Detention

According to a lawyer who represents immigration detainees in Japan, to date the Immigration Services Agency has taken no action to safeguard or release detainees. This has prompted NGOs and advocates in the country to issue an appeal on the Immigration Review Task Force Facebook page demanding urgent action by the government. […]

Last updated: March 2013

Japan Immigration Detention Profile

Japan’s foreign-born population has almost doubled in the last two decades, reaching more than two million by 2011 (MoJ, 2012), driven in large measure by labour demands. Most foreign nationals come from Asian countries, notably China, the Koreas, and the Philippines, as well as Latin American descendants of Japanese immigrants (MoJ, 2012).

Despite this surge in foreigners residing in the country, Japan’s international migrant population remains quite small as a percentage of its overall population. According to the OECD, as of 2011, Japan’s percentage was 1.7, compared to 25.8 in Switzerland, 25.4 in Australia, 20.2 in Canada, 15.3 in Austria, and 13.7 in the United States. Nevertheless, the recent influx of foreign nationals in Japan has divided public attitudes. Keidanren, Japan’s business federation, advocates a more favourable environment for importing migrant workers (Keidanren 2010, 2011). Public opinion surveys, however, reveal a more mixed reaction among the general population. In 2004, 60 percent of respondents said that Japan should accept migrant workers while 30 percent were against it, arguing that innovation and full utilization of women and aged labour could make up for shortfalls (Cabinet Office 2004). More recently, a 2010 survey revealed that larger majorities of the public considered having Japanese language skills (94 percent) and understanding Japanese customs (89 percent) as important than having technical skills and knowledge (74 percent) (Cabinet Office 2010).

Foreign nationals face significant difficulties integrating into Japanese society. In 2010, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants reported that “racism and discrimination based on nationality are still common in Japan, including in the workplace, schools, housing, the justice system and private establishments.” He urged Japan to address various challenges in order to meet international human rights standards (SRHRM 2011, paras. 36, 78).

Immigration policy has aimed to reduce the numbers of non-nationals in irregular situations while accelerating immigration of skilled workers. An important tool used for implementing this policy has been mandatory detention of over-stayers and other unauthorized migrants. Many of the country’s detention policies and practices—including the lack of detention time limits, the detention of asylum seekers, poor conditions of detention facilities, and lack of access to health care—have been repeatedly criticized by the international community as well as national civil society (SRHRM 2011; Shoji 2010, 2012; Yamamura 2005).

Pressure from these actors and demonstrations by detainees have helped spur some changes, including reductions in the numbers of child detainees and minor improvements in detention conditions. Nonetheless, operations at detention centres remain at the discretion of the director of each immigration facility (for example, with respect to the length of free time and tolerance of religious events), leading to claims of unequal and arbitrary treatment (Shoji 2012).

Detention Policy

Key norms. The principal norms applicable to the administrative detention of non-nationals are contained in the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, Act No. 319 of 1951 (ICRRA). This law has been reviewed and amended a number of times, including in 1982 and following the ratification in 1990 of theConvention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol.

Grounds for deportation. Article 24 of ICRRA contains a detailed list of persons subject to expulsion from the country. These include persons who have: (1) entered irregularly or overstayed their visas; (2) committed certain crimes; (3) forged documents; (4) been involved in unauthorized income-generating activities; (5) been in involved in migrant trafficking; or (6) been suspected of terrorist activities.

Grounds for detention and mandatory detention. Article 39 provides that an immigration control officer may detain non-nationals suspected of falling into one of the categories outlined in Article 24. Officials of the Immigration Bureau are generally responsible for initiating deportation procedures and issuing detention orders. Although the law makes detention decisions discretionary, the Japanese government and Immigration Bureau apply the principle of Zenken-Shuyo Shugi(literal translation is “detention of all violators,” which signifies mandatory detention) in practice.

Observers confirm that in practice detention is mandatory for all foreign nationals facing deportation, although the Immigration Bureau provides discretionary provisional release. “As a policy, the Immigration Bureau detains all foreigners that it suspects of violating the Immigration Control and Refuge Recognition Act, and allows temporary release only discretionarily. The government says that it tries to avoid detaining minors and that, if it does detain them, it gives consideration to detaining them for the shortest time possible” (JFBA 2009, para 57).

The government of Japan underscored this fact in 2006 correspondence with the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants, stating: “Detention is mandatory throughout this entire [deportation] process unless it its deemed necessary, according to the circumstances of a particular case, to release the detainee” (SRHRM 2006, para. 135).

The Immigration Bureau also clearly mentioned on their website (as of February 2013) the existence and practice of Zenken-Shuyo Shugi (mandatory detention), as well as the fact that exemption from detention is considered only in exceptional cases. “In order to drastically reduce the number of illegal foreign residents, it is necessary to encourage such foreign residents to appear at the regional immigration bureaus voluntarily as well as to establish a system whereby letting them depart from Japan promptly and efficiently through effective use of the limited human resources at the regional immigration bureaus. To achieve this, a departure order system has been established under which, as an exception to the principle of detention of all violators, illegal foreign residents who satisfy certain requirements may depart from Japan without being detained in accordance with simple procedures (enforced since December 2, 2004)” (Immigration Bureau website).

Detention of children. In contrast to international law, Japan defines “minors” as anyone under the age of 20. Minors are subject to administrative immigration detention in Japan. However, the numbers of detained minors appears to have dropped significantly during the last decade.

In 2002, 318 children were held in detention facilities: 135 were under 6; 66 were between 6-12; 26 were between 12-15; 91 were between 15-18. In addition, Japan detained 315 young adults between the ages of 18-20 (House of Representatives 2003). During that year, minors and your adults were generally detained for periods of less than 50 days. Out of 633 individuals under age of 20, some 465 were detained for less than 10 days. However, in a few cases, children were detained for more than 100 days (House of Representatives 2003).

As of November 2012, there were only five minors detained in two detention facilities, namely the Higashi Nihon Detention Centre and the Tokyo Immigration Bureau. All were male (Immigration Bureau 2012). Official statistics do not clarify whether these detainees included anyone under the age of 18. This figure may include the young adults between the ages of 18-20.

In February 2013 email message to the Global Detention Project (GDP), Kimiko Tanaka of Ushiku-no-Kai, an NGO that conducts weekly visit to the Higashi-Nihon detention centre, said that while previously children were detained at that facility, more recently authorities granted provisional release to anyone under the age of 18. However, she also claimed that the detention facility of the Tokyo Immigration Bureau allows small children to be detained alongside their mothers in the same room (Tanaka 2013).

Similarly, a representative of the Japan Association of Refugees told the GDP that “although until very recently Japan did detain minor asylum-seekers in immigration detention,” the practice appears to have ended sometime around 2010. “Currently, in practice, minor asylum seekers (defined in Japanese law as those below the age of 20) do not appear to be detained—at least we are not seeing any applicants of that age who are detained.” He added, “What I am describing is what is happening in practice. There is no clearly stated and publicly available policy from the government that they will not detain children, it is just that statistically and in our experience we have not seen any instances of the detention of minor asylum-seekers in the last two years” (Barbour 2013).

Japan is a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, although it has a reservation with respect to a detention-related provision in the treaty. The reservation states: “In applying paragraph (c) of article 37 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Japan reserves the right not to be bound by the provision in its second sentence, that is, ‘every child deprived of liberty shall be separated from adults unless it is considered in the child's best interest not to do so,’ considering the fact that in Japan as regards persons deprived of liberty, those who are below twenty years of age are to be generally separated from those who are of twenty years of age and over under its national law."

Additionally, Prime Minister Koizumi stated in 2003 about the convention: “It is considered that the article 3-(1) of the convention requests state parties to take into account the best interest of children as one of the main considerations when state parties take administrative measures. It does not exclude other factors such as the interest of parents and public interest. Thus, it is presumed that taking administrative measures, which may have an undesirable effect on interest of children, are not necessarily excluded by taking account those factors. [...] It can be considered that the detention during the deportation procedure is not a violation of article three of the Convention on the Rights of the Child” (House of Representatives 2003).

Numerous domestic and international bodies have criticized Japan’s detention of minors. In the report on his 2010 visit to Japan, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants stated that the detention of minors and their parents should be avoided (UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants 2011, para.82). In 2010, the Japan Bar Association cautioned the Minister of Justice that the detention of children should not be done based on policy of Zenken Shuyo Shugi (“detention of all violators”), and that the necessity of detention should be examined on a case by case basis.

Detention of asylum seekers. Japan has ratified the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. In 1982, the country amended ICRRA to incorporate provisions of the treaties and establish asylum procedures. In 2005, ICCRA was amended to provide that appeals of negative decisions on asylum applications be decided at a hearing before a body constituted by independent experts from outside the Ministry of Justice (For a review of the amendment see the Japan Federation of Bar Associations 2006).

Asylum applications must be filed with the Immigration Bureau and are examined through an administrative procedure of the Ministry of Justice. Applicants do not have access to government-sponsored legal aid but may be aided by pro bono attorneys working with the UNHCR. If an appeal is rejected, asylum seekers can appeal to the regular courts under the Administrative Case Litigation Law (ACLL).

Asylum seekers can be detained during proceedings as provided by Articles 39–43 of the ICRRA. However, in certain cases asylum seekers may be entitled to a temporary permit (ICRRA Article 61-2-4). State-sponsored legal aid is not available to asylum seekers(For a detailed description of the asylum process see Meryll 2006). In 2012, there were 238 asylum seekers detained in detention centres and regional immigration bureau according to Ministry of Bureau (MoJ 2012). However, these figures do not include asylum seekers potentially detained in in departure waiting facilities.

Detention of victims of trafficking. As of 2012, the trafficking of human beings is treated under criminal code and ICRRA. Japan adopted a National Action Plan to Combat Trafficking in Persons in 2004, after being criticized about the human trafficking situation and treatment of victims by Japanese civil society and the international community for many years. A number of measures have been taken in order to combat trafficking, including: the criminalization of human trafficking; the provision of special resident permits to victims of trafficking; and the stricter application of “entertainment visas” (which have been widely used to facilitate trafficking in persons, often bringing Asian females to entertainment industry or even sometimes sex industry in Japan) (Ministerial Meeting Concerning Measures Against Crimes Japan 2004, 2009; Committee Against Torture, Concluding Observations 2007, para. 25; Fujimoto 2006, 2007).

The criminal code was amended in 2005 to criminalize the conduct of buying and selling of persons, and the conduct of transporting, transferring, and the harbouring of victims of kidnapping, abduction, buying, or selling (Criminal Code Arts. 224-229). Additionally, the ICRRA was amended in 2005. It stipulates that victims of trafficking are eligible for special permission for residence and shall not be deported. If the trafficking victims wish to return to their home country, their departure will be facilitated as “a legal resident” (Immigration Bureau 2005).

In 2011, the Immigration Bureau detected 21 victims of trafficking, 13 of whom were from Philippines, the rest from Thailand. Six of these people had regular status, while 15 were in irregular status (mainly over-stayers). All of 15 were accorded special permission to stay from humanitarian perspective (MoJ 2012).

Victims of trafficking are given protection in Women’s Consulting Centre shelters, which hosts mainly Japanese victims of domestic violence, or NGO shelters. In the former, the expenses for medical care is wholly covered by the Japanese government; however, the victims may not receive sufficient support due to limited space, language and counselling capabilities of Women’s Consulting Centre shelters (US Department of State 2012).

Detention at ports of entry. Persons who are stopped at ports of entry without proper documentation are granted a hearing with a Special Inquiry Officer (ICRRA Art.10-11). Such persons may be ordered to stay in designated facilities in the vicinity of the port of entry or departure while awaiting deporation or the conclusion of other immigration-related procedures (ICRRA Art.13-2). In practice, they are placed in what are known as “Landing prevention/Departure waiting facilities.” Article 52-2 of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the ICRRA defines these facilities as “Accommodation facilities near Narita, Haneda, Chubu, and Kansai airport designated by Minister of Justice,” which also include private hotels.

The most recent official information that the Global Detention Project has seen regarding operations of landing prevention facilities comes from a 2007 internal regulation called the “Management Rule of Landing Prevention Facilities.” These facilities are located inside airport buildings (Amnesty 2002, Shoji 2012, JLNR 2006). There is limited information about how those facilities are run; however, a 2006 budget review by the Japan Ministry of Finance revealed that JPY 95,000,000 (USD 1,012,793) were allocated for the management of these landing facilities in FY2007. This included expenses to contact private security companies to provide services at the facilities (MoF 2006).

The Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) argued in 2007 that there were no legal grounds for detaining people in landing prevention facilities and that there was an absence of clear rules concerning the treatment of detainees in such facilities (JFBA 2007, paras. 197-206). A 2009 Amendment of ICRRA included “detention places” in article 61-7, making detainees in landing prevention facilities treated under the same legal ground as other immigration detention centres (ICCRA Art. 61-7). However, information about landing prevention facilities remains limited compared to other immigration detention centres. Thus, for example, statistics about detainees in landing prevention facilities were not included in 2012 Immigration Bureau responses to inquiries from the Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan (Immigration Bureau 20 November, 2012).

ICCRA reforms. An important amendment to ICRRA was adopted in July 2009 (MoJ website 2009). The amendment, which entered into force in 2012, provides for the creation of a system of residence management that includes issuance of a “Residence Card,” replacing the previous alien registration system. Under the previous system, both documented and undocumented non-citizens could obtain an “Alien Registration Certificate.” Under the new system, irregular non-citizens are no longer able to obtain valid identity documents from immigration authorities. Rights groups in Japan have repeatedly expressed concern that this change in policy will lead to social exclusion of immigrants, especially those in an irregular situation, in part because it will limit the ability of migrants to receive social services and subordinate the core functions of local government to immigration control (see, for example, the website of the NGO Committee against the introduction of "Zairyu Card" system).

In response to these concerns, the government adopted supplementary provisions to ICCRA and Residential Basic Book Act in the process of ICCRA reform, which stipulates that irregular migrants who are accorded provisional release can receive administrative services (see supplementary provisions to ICCRA, art. 60, July 15, 2009; supplementary provisions to the Residential Basic Book Act, art. 23, July 15, 2009).

In a statement issued after these reforms were adopted, the Japan Federation of Bar Associations stated: “We request local governments to act based on the premise that implementation of amended ICRRA does not change [human] rights itself, which should be assured to foreign nationals without documentation” (JFBA 2012, website).

Other relevant laws and regulations include the Treatment of Detainee Regulation (Ministerial Ordinance number 59 of 1981, last amended with Ministerial Ordinance 43 of 2011); the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (Ministerial Ordinance number 16 of 1990, last amended with Ministerial Ordinance 37 of 2012); the National Redress Law; the Protection of Personal Liberty Act; and the Administrative Case Litigation Law.

The Treatment of Detainee Regulation provides general guidelines for the treatment of detainees in immigration detention facilities. It includes, inter alia, provisions regarding equipment in detention centres, access to health services, and access to visitors.

The Ordinance for the Enforcement of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act defines administrative details for implementing the ICRRA, such as processes to request landing (Art. 5), the scope of provisional landing (Art. 12), and contents of residence cards (Art.19).

Detainees who wish to contest their deportation order or their detention during deportation procedures can request a judicial review of these orders as per provisions in the Protection of Personal Liberty Act or the Administrative Case Litigation Law. People can request compensation for illegal detention under the National Redress Law (CCPR/C/JPN/5, para 170. (d)(e)).

In 2003, a “Ministerial Meeting Concerning Measures against Crime” adopted an Action Plan to combat crime that included “halving non-citizens in an irregular situation in five years.” The plan spurred authorities to tighten border control, including collection of fingerprints and picture of foreigners, detection of forged documents, and the expansion of detention facilities. During the five-year period covered by the plan, the estimated number of over-stayers was reduced from 220,000 in to 113,000 (MoJ 2010, p.23).

Criminalization. Article 70 of ICCRA provides criminal punishments for violations of a number of immigration related provisions, including illegal entry and overstaying. Punishments include up to three years imprisonment and/or a fine up to JPY3,000,000 (USD 32,000) (ICRRA Art. 70). Officially recognized refugees and asylum-seekers who declared asylum immediately after the entrance or expiration of the permitted period of stay, are exempt from these penalties (ICRRA Art. 70-2).

Length of detention. There is no maximum limit to the duration of administrative immigration detention. Immigration officials can issue a detention order for an initial period of 30 days when there is “reasonable grounds to believe that a suspect falls under any of the items of Article 24.” This can be extended for an additional 30 days (ICRRA Arts. 39, 41). Once a deportation order is issued, there is no limit on the amount of time a person can remain in detention. The detainee may be held “until such time as deportation becomes possible” (ICRRA Article 52.5).

After his visit to the country in 2010, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants stated, “Under no circumstances, detention should be indefinite,” and recommended that Japan set a maximum period of detention pending deportation (A/HRC/17/33/Add.3. para. 83).

During the first 48 hours after being apprehended, the person shall be delivered by an immigration control officer to an immigration inspector in order to determine whether he/she falls under one of categories provided under Article 24 of ICRRA (ICRRA Art.44). If, upon examining the evidence, it is determined that Article 24 is not applicable, the immigration inspector must immediately release the person (ICRRA Art. 48-6).

An immigration control officer can also detain a person without a written detention order if there is a reasonable ground to believe that potential detainee will flee before issuance of a written detention order. In this case, the immigration officer is required to notify supervising immigration inspector and request the issuance of a written detention order immediately after the apprehension (ICRRA Art. 43).

Review of detention decisions. Detention orders are issued by immigration officials and are not subject to control by the judiciary. However, a detainee must be presented within 48 hours from the moment when he or she is taken into custody to an Immigration inspector who will examine the evidence on which the detention is based (ICRRA Art.44). The burden of proof in such procedures is on the detainee (ICRRA Art.46).

Challenging detention and deportation. ICRRA provides that all persons in immigration detention proceedings be given adequate information about their situation, which includes: being shown the detention order containing information about the reasons for the person’s detention (ICRRA Art. 42); being notified of the decision to expel (ICRRA Art. 47.3); and being shown the deportation order at the moment of enforcement (ICRRA Art. 52.3).

The detainee can request a hearing with a Special Inquiry Officer (ICRRA Art. 48). If he or she does not agree with the findings of the Special Inquiry Officer an objection can then be filed with the Minister of Justice (ICRRA Art. 49). When for whatever reason the detainee cannot be immediately deported, he or she may be detained or continue to be held “until such time as deportation becomes possible” (ICRRA Art. 52.5). If it is found that the person is not deportable the director of the centre can release him or her under certain conditions (ICRRA Art. 52.6).

In 2011, Special Inquiry Officers processed 8,577 cases; only three were considered not to have merit. That same year, 8,558 cases were investigated by the Minister of Justice; of these, seven were ruled to be non-violations, 6,879 were given special permission to stay, and 1,600 were issued deportation orders (Statistics bureau e-stat 2012). The large number of special permissions contrasts dramatically with the small number of judgements of non-violations, as well as with the small number of refugee recognition cases (21 in 2011, MoJ 2012).

Deportation orders can be challenged in court pursuant to the Protection of Personal Liberty Act of the Administrative Case Litigation Law (SRHRM 2006, para. 135). In 2011, the Immigration Bureau lost five cases (Immigration Bureau 2012).

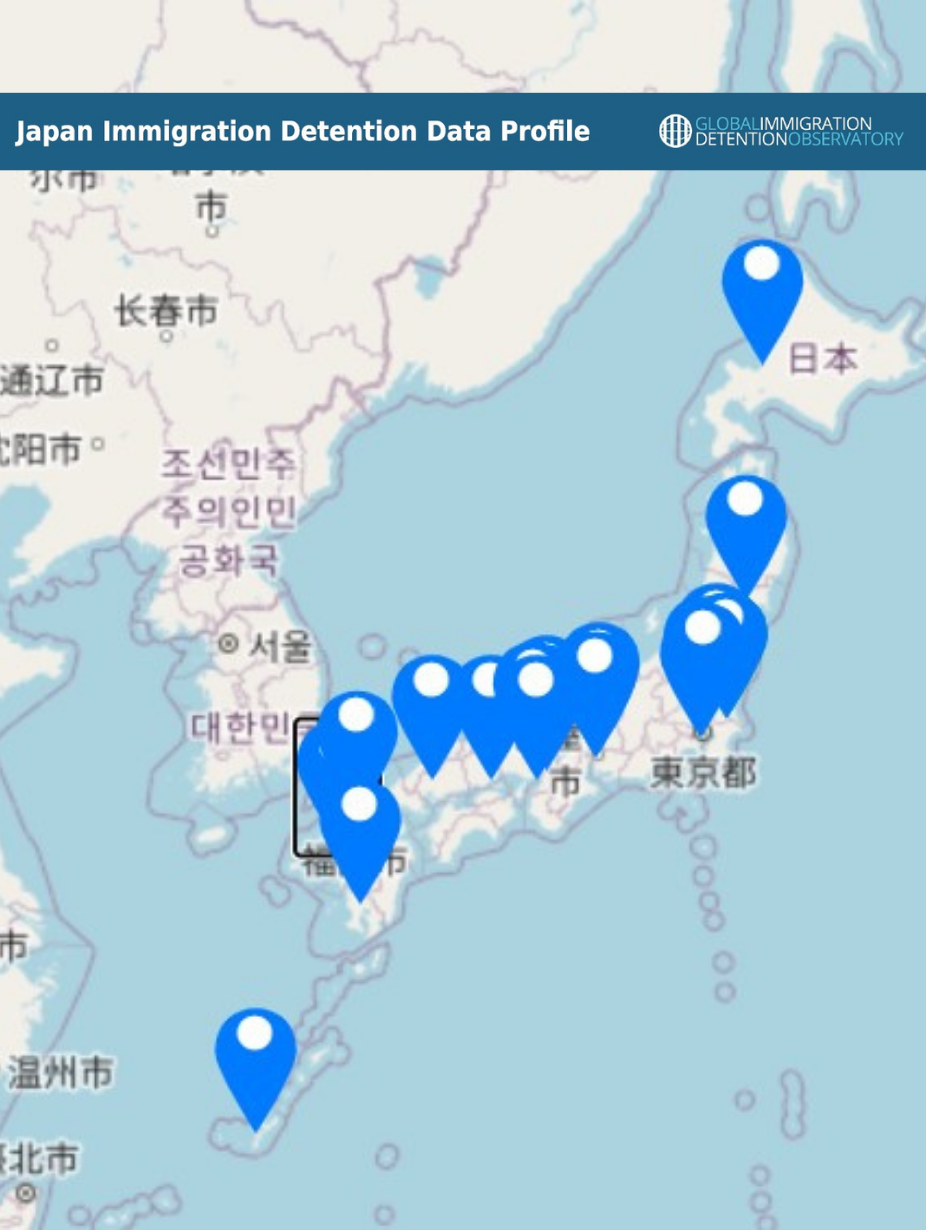

Relevant government agencies. The Immigration Bureau, a branch of the Ministry of Justice, is responsible for the implementation of immigration legislation. The bureau has eight regional bureaus, seven district immigration offices, including airport immigration offices, and 61 branch offices. As of 2012, all eight regional bureaus, seven district immigration offices, and one branch office had detention facilities (Immigration Bureau 2012).

The country’s three main long-term immigration detention centres—Higashi-Nihon Detention Centre, Nishi-Nihon Detention Centre, and Omura Detention Centre—are under the authority of the Ministry of Justice. While there are no publicized data on the average length of detention in regional detention bureaus and detention centres, it is common practice that detainees are sent to one of three main detention centres when it is expected that duration of detention will be prolonged (Shoji 2012).

The Immigration Bureau’s authority to issue deportation and detention orders is established in a 2000 Ministry of Justice “cabinet order.” The same order establishes that the “guard department” is responsible for the implementation of such orders (Cabinet Order on Organization of Ministry of Justice 2000, Arts. 54 and 55).

ICCRA provides that an immigration control officer can detain an individual who is suspected of violating specific immigration provisions Article 24-1 based on the detention order issued by an immigration inspector (ICRRA Art. 39). Additionally, the law authorizes the police, at the request of a supervising immigration inspector, to place a suspect under custody in a detention facility (ICRRA Art. 41.3).

Detention sites, detention conditions, and complaints procedures. ICRRA specifies that non-nationals detained under its provisions can be held at an “immigration detention centre, detention house, or any other proper place designated by the Minister of Justice or by a supervising immigration inspector commissioned by the Minister of Justice” (ICRRA Art. 41.2). Moreover, according to the law, a police official may, on the request of a supervising immigration official, place a suspect under custody in a detention facility (ICRRA Art. 41.3).

ICRRA also establishes the minimum treatment that must be accorded detainees, including that they be given maximum liberty consistent with security requirements and be provided with adequate food, bedding, accommodation, and sanitation (ICRRA Art.61-7).

Regulations on the treatment of detainees were issued by the Ministry of Justice in 2001 and are applicable to non-nationals held in administrative detention. The regulations established an administrative complaint procedure known as an "Appeal of Complaint" whereby detainees can file complaints with the Immigration Bureau regarding their treatment by immigration officials. Such complaints must be filed within seven days after of the alleged facts. Once a complaint is made, the director of the detention facility must investigate the case and adopt a decision.

However, concerns have been raised about the effectiveness of this procedure. The overwhelming majority of complaints to date seem to have been dismissed for lack of sufficient evidence (CAT Network Japan 2007, paras. 217-220; Japan Federation of Bar Associations 2007, paras. 213-214).

There were numerous hunger strikes at detention centres during 2010 to 2012. The demands from detainees included: 1) the granting of provisional release; 2) avoidance of prolonged detention or repeated detention after provisional release; and 3) improvement of detention conditions (Shoji 2012).

Detainees wishing to complain of torture may file civil or administrative lawsuits regarding their treatment before the courts sunder the State Tort Liability Law. However, it should be noted that Article 6 of that law requires reciprocity so that foreign nationals from countries that do not recognize the right of Japanese citizens to demand state compensation cannot themselves file for redress. Both the Committee Against Torture (CAT) and the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) have raised concerns regarding this requirement (see CAT 2007, para. 23; and CERD 2001, para. 29).

Detention monitoring. In July 2010, an official Immigration Detention Facilities Visiting Committee was established based on the amendment of ICRRA in 2009. There are separate committees in the east and the west of the country. The Committees conduct inspections in detention facilities and interview detainees in an effort to increase transparency regarding the treatment of detainees (Arts 61-7-2-2, 61-7-4-2 and 61-7-6, ICRRA, MoJ website). Each committee is comprised of 10 individuals appointed by the Minister of Justice (Art. 61-7-3, ICRRA). In practice, two members are from academia, two from juridical circles, two from the health care industry, two from either international organizations or NGOs, and two from local communities (MoJ 2012 website). During the period July 2010-June 2012, the committee visited all 19 detention facilities in the country (not including the landing prevention facilities), conducted 75 interviews with detainees, and provided recommendations to directors of the regional immigration bureaus (MoJ 2012 website).

Article 61-7-5 of ICRRA requests that the Minister of Justice publicize the summary of recommendations made by the committee, as well as the measures taken to improve detention facilities. This process has reportedly led to the adoption of some measures to improve conditions at detention centres. These include the purchase of additional equipments in the detention facilities, such as partitions in meeting rooms and mats in gymnasiums, counselling to improve the mental health of detainees, and usage of appropriate shoes for sports (MoJ 2012).

NGOs and volunteers regularly visit detention centres. For example, Ushiku-no-Kai is an active NGO, which visits Higashi Nihon Immigration Centre on a weekly basis. Each member of the group meets with several detainees in a day, trying to mentally support the detainees, obtain information about condition of detainees and the facility, as well as providing advice to how to better off under that condition (Typically, they encourage detainees to learn Japanese language and offer some learning material).

Non-custodial measures. Migrant detainees can request provisional release from immigration authorities (Art 54, ICRRA). The director of the immigration detention centre or a supervising immigration inspector may accord provisional release, with payment of deposit, which is not to exceed 3 million yen. Provisional release can include restrictions on the place of residence and movement and the obligation of appearance upon the demand from the immigration bureau (Art 54-2, ICRRA). Private visa application services and law firms claim that deposits usually do not exceed 600,000 yen (see Acroseed). Immigration authorities may also accept the letter of guarantee in the substitution of deposit (Art. 54-3).

Provisional release may be revoked when the person concerned has fled or failed to meet the condition of provisional release such as obligation to appear upon the request, or when the director of the immigration detention centre or the supervising immigration inspector considers that there is a reasonable ground to suspect that the person concerned may flee (Art. 55, ICRRA).

During the period of January-September 2012, 345 people were given provisional release, all of whom provided guarantors. The total number of people with provisional release reached 3,814 as of October 2012 (Immigration Bureau 2012).

Detention Infrastructure

Japan employs a variety of facilities for administrative immigration-related detention. These include specialized, long-term immigration detention centres, “detention houses” in regional immigration offices, “departure waiting facilities” (also called “landing prevention facilities”) in airports, and airport “rest houses” (ARHs).

Airport facilities are intended to hold people denied entry into the country; detention houses in immigration offices, although sometimes used for long-term detention, appear to be used mainly to hold people for brief periods of time, until they can be transferred to a longer term dedicated immigration detention centre (CAT Network Japan 2007; Yagishita 2007; Shoji 2012). All detention facilities are under the authority of the Immigration Bureau, but landing prevention facilities have been operated by private security firms (Amnesty International 2002; Dean 2006).

The Immigration Bureau, which is part of the Ministry of Justice, maintains a total of 16 detention houses and three long-term immigration detention centres, which have a combined total capacity of 4,010 (as of 2012). The detention houses are located at the regional immigration bureaus, district immigration offices, and some branch offices. These can be found in the regional immigration bureaus of Sapporo, Sendai, Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Hiroshima, Takamatsu, Fukuoka; district immigration offices of Narita airport, Haneda airport, Yokohama, Chubu airport, Kansai airport, Kobe and Naha; and the branch office of Kagoshima (Immigration Bureau 2012).

The three immigration detention centres are: Higashi-Nihon Immigration Centre in Ushiku (Ibaraki Prefecture), Nishi-Nihon Immigration Centre in Ibaraki City (Osaka Prefecture), and Omura Immigration Centre in Omura (Nagasaki Prefecture) (Immigration Bureau website).

Departure waiting/landing prevention facilities (DWFs/LPFs) are located in at least four airports: Narita, Haneda, Chubu, and Kansai. The Global Detention Project has been able to uncover very few details about these facilities. For instance, only the capacity of the Haneda airport appears to be publicly available. It can accommodate a maximum 10 people in 4 rooms (Haneda Airport District Immigration Office 2011). In addition to these, the Immigration Bureau makes use of a privately-owned hotel, or "rest house," located inside the terminal of the Narita Airport, near Tokyo. This facility, called the Narita Airport Rest House, is sometimes used to hold members of families (mainly women and children) denied entry into Japan while other famlies members are confined at the airport's landing prevention facility (Shoji 2012). The GDP codes this site a "semi-secure" "ad hoc" transit facility because it is a hotel where private security guards apparently restrict the freedom of movement of those confined there, though it is unclear to what degree (JLNR 2006; Shoji 2012).

Rights experts have claimed that asylum seekers are often detained at airport facilities, although these reports are several years old. During its visit to the facility at Narita Airport in 2000, Amnesty International found that “a daily average of some seven persons were detained in the LPF” (Amnesty International 2002). Other observers have estimated that thousands of people are denied entry into Japan (including asylum seekers) and detained in LPFs and ARHs prior to their deportation (Dean 2006). According to one report, “Detention also extends to those whom UNHCR [UN High Commissioner for Refugees] has mandated but who are seeking judicial review of their refusal by the government” (Dean 2006). Five UNHCR-certified refugees were detained at the end of 2003. The number decreased to three at the end of 2004 (Dean 2006).

In November 2012, a total of 1,104 people were in detention in immigration facilities (not including the airport facilities): 375 in Higashi-Nihon detention centre, 80 in Nishi-Nihon, and 25 in Omura; one in Sapporo Regional immigration bureau, four in Sendai, 359 in Tokyo, 137 in Nagoya, 59 in Osaka, one in Fukuoka; 15 in Narita Airport district immigration office, 48 in Yokohama (Immigration Bureau 2012). No official figures are available on the number of detainees in airport facilities.

A comparison of detainee statistics from different types of detention facilities reveals key characteristics of how detention centres and detention houses in immigration offices operate. For example, the Tokyo regional immigration bureau held 9,223 detainees during 2011, while the number of detainees as of 5 November 2011 was 359. Among these 359 detainees, only four detainees had been in detention for more than six months.

On the other hand, the Higashi-Nihon detention centre held 375 individuals as of 5 November 2011 and hosted 766 detainees in total in 2011. In contrast to the detention statistics at immigration office facilities, a majority of the detainees (270) at the Higashi-Nihon centre were detained for more than six months. These figures seem to reveal how people facing lengthy detention terms are transferred from immigration offices to detention centres.

In 2011, total number of detainees was 23,133, of whom 13,430 were male and 9,703 were female.

Most detainees come from Asia or Latin America. In 2011, detention orders were issued for 14,924 individuals, of whom 3,932 were from China, 3,710 from the Philippines, 1,852 from the Koreas (North and South), 904 from Thailand, 673 from Brazil, and 504 from Peru. Other nationalities included Vietnamese, Sri Lankan, Indonesian, and American (Statistics bureau of Japan 2011). The top five nationalities of overstayers that year were Korean, Chinese, Philippino, Taiwanese, and Thai (MoJ 2012).

Conditions of detention. Immigration detention facilities are reputedly prison-like, including the widespread use of cells to confine detainees. Human rights groups have reported numerous abuses at detention facilities over the years, including physical, verbal, and sexual abuse; substandard detention conditions, overcrowding and poor sanitation; denial of access to medical services and insufficient opportunity to undertake physical exercise; and excessive restrictions on detainee’s ability to communicate with family members and legal representation (Amnesty International 2002; Human Rights Watch 2000; Dean 2006; CAT Network Japan 2007; Japan Federation of Bar Associations 2007).

The conditions of detention vary. Some facilities have two-person cells, other have rooms that accommodate up to eight people. In the Higashi Nihon Detention centre, meetings between detainees who are in different blocks are limited as a result of changes made after repeated hunger strikes in 2010. Detainees in different blocks can meet each other in only special occasions. On the other hand, there are some facilities, such as Narita immigration bureau, that allow married couples to spend time together, even if they are in different blocks. However, those measures are taken only at the discretion of the director of detention facility (Shoji 2012).

Detainees generally have access to common rooms, recreational grounds, and laundry facilities (Shoji 2012). The length of time detainees can walk freely around specified areas of facilities varies. Detention centres, which are designed for long-term detention, allow between 5-7 hours per day. On the other hand, there is no such at 10 detention houses in immigration offices due to “structures of facilities” (Immigration Bureau 2012). In an email message to the Global Detention Project, the Refugee coordinator of Amnesty International Japan said that because detention houses are located inside local immigration branch offices, they are usually small and in some cases do not have required facilities such as exercise areas and public phones (Yagishita 2007).

Also, there have been reports of detainees spending long periods of time in isolation as a disciplinary measure. Immigration centres have isolation rooms to seclude detainees in order to “protect the life and body of the detainees and to maintain order within the facility” (Commission against Torture 2007). According to one report, there have been “several cases” in which these types of rooms have been “the locality for the abusive treatment of detainees” (CAT Network Japan 2007). There have also been complaints regarding the discretionary authority given to the director of immigration centres to decide the period of isolation, which in one case led to an unsuitably long isolation period (Japan Federation of Bar Associations 2007). In 2011, 171 male and seven female detainees were confined in isolation facilities. The longest time in isolation during this period was 13 days (Immigration Bureau 2012).

Detainees in the immigration centres have the right to communicate with the outside world and receive visits (Immigration Bureau). Visitors, such as NGOs, family members, supporters, and lawyers, can meet detainees for up to 30 minutes (Shoji 2012). It has been reported that letters from detainees are censored (Committee against Torture 2007) and telephone calls are limited (CAT Network Japan 2007).

According to the few reports available about airport facilities, conditions tend to be severe at them. They are sometimes overcrowded and lack windows and exercise spaces. Moreover, communications are restricted and there is a limited access to medical care (Japan Federation of Bar Associations 2007). According to Amnesty International Japan, there have been cases these facilities refuse to allow NGOs to contact detainees in, sometimes by claiming “there is no such person in the facility.” These restrictions, says Amnesty, are a result of the fact that detainees at these facilities are considered not have officially entered Japan (Shoji 2012).

An NGO report from the early 2000s reported that that foreign nationals—including asylum seekers—who were denied entry to Japan suffered ill treatment during the interrogation process and detention period at airport facilities. Some were denied access to interpreters during the interrogation process, and some detainees were refused contact with their families, diplomatic missions, or legal advisers. Additionally, information about the refugee status determination process was not available freely or in languages that the detainees could understand (Amnesty International 2002).

Facts & Figures

As of November 2012, there were 1,104 immigration detainees in Japan (not including those detained in airport facilities). Of these, 236 had been in detention for between 6-12 months, 75 between 12-18 months, and 24 for 18-24 months (Immigration Bureau 2012).

Japan operates 19 secure facilities for the administrative detention of foreign nationals, excluding airport landing prevention facilities. There are three long-term dedicated immigration detention centres, which have a total capacity of 1,800; eight regional immigrations bureaus and eight immigration bureau branches, which have a total capacity of 2,210 (Immigration Bureau 2012).

The Japanese government has been criticized for not adopting a limit on the length of immigration detention. In a majority of cases, detention is less than six months; however, there are also cases exceeding one year. In 2007, the total number of detainees was 1,653, of whom 1,535 were detained for less than six months, 91 were detained for 6-12 months, 23 were detained 12-18 months, and four were detained for 18-24 months (House of Councillors 2007). As of November 2012, the number of detainees was 1,104, of whom 236 had been in detention for 6-12 months, 75 for 12-18 months, and 24 for 18-24 months (Immigration Bureau 2012).

In 2010, 2,134,151 foreigners were registered in Japan (MoJ 2011, p.19), accounting for just over 1.5 percent of the country’s total population. Main source countries at the time were China (687,156), North and South Korea (565,989), Brazil (230,552), Philippines (210,181), and Peru (54,636).

Immigration authorities estimate that in 2011 there were between 90,000 and 100,000 undocumented migrants in Japan, including 78,488 overstayers. The number of overstayers has been halved in last five years. Most come from Asian countries: South Korea (19,271), China (10,337), Philippines (9,329), Taiwan, Province of China (4,774), and Thailand (4,264) (MoJ, 2011, p.34).

Japan’s refugee recognition rate tends to be very low. In 2010, out of 1,202 applications, only 39 were given refugee status while and additional 363 were given permission to stay for humanitarian reasons (MoJ 2011, p.52-53).

References

- Amnesty International, Japan. 2002. “Welcome to Japan?” ASA 22/002/2002. http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3ce502664.htm.

- Asis, Maruja M.B. 2004. “Not Here for Good? International Migration Realities and Prospects in Asia.” Japanese Journal of Population, Vol. 2 (1) (2004): 18-28.

http://gsti.miis.edu/CEAS-PUB/2003_Cameron.pdf - Barbour, Brian (Japan Association of Refugees). 2013. Email communication to Michael Flynn (Global Detention Project). Geneva, Switzerland. 20 February 2013.

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. 2004. “Survey on acceptance of Migrant Labor”. 2004. http://www8.cao.go.jp/survey/h16/h16-foreignerworker/index.html.

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. 2010. “Survey on International Labor Migration”. 2010. http://www8.cao.go.jp/survey/h22/h22-roudousya/index.html.

- Cameron, Sally. 2003. “Trafficking of Filipino Women to Japan: A Case of Human Security Violation in Japan.” Human Flows Project Research Paper, Monterey Institute of International Studies, 2003.

http://gsti.miis.edu/CEAS-PUB/2003_Cameron.pdf. - CAT Network Japan. 2007. The Alternative Report on the Japanese Government’s Report of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. March 2007.

- Clamme, John and Miyoko Ogishima. 2006. Migration, Foreign Workers, Gender and Social Policy: A Japan Country Report, ASERA ASPAC Network on the Empowerment of Women Migrant Workers.

http://www.asera-aspac.net/upload_files/9/Japan%20Migrant%20Workers.pdf. - Clark, Gregory. 2005. “Japan’s Migration Conundrum,” ZNet, February 9, 2005, http://www.zmag.org/content/showarticle.cfm?ItemID=7215.

- Cornelius, Wayne A. 1994. “Japan: The Illusion of Immigration Control.” In Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective, edited by Wayne A. Cornelius, Philip L. Martin, and James F. Hollifield, 375–410. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994.

- Dean, Meryll. 2006. Japan: Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Writenet Report, 2006.

- French, Howard W. 2003. “Insular Japan Needs, but Resists, Immigration,” New York Times, July 24, 2003,http://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/24/international/asia/24JAPA.html.

- Fujimoto, Nobuki (Hurights Osaka).

フィリピンパブの盛衰から人身売買を考える

http://www.hurights.or.jp/japan/aside/human-rights-of-migrants/2006/08/post-2.html. - Government of Japan. 2006. The Fifth Periodic Report by the Government of Japan Under Article 40 Paragraph 1(b) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, December 2006.

- Haneda Airport District Immigration Office. 2011. “Outline of Business Operations”. (In Japanese) 2011.

http://www.moj.go.jp/content/000081918.pdf. - House of Councillors. 2007. House of Councillors reply number 80. 18 December 2007.http://www.sangiin.go.jp/japanese/joho1/kousei/syuisyo/168/touh/t168080.htm.

- House of Representatives. 2003. House of Representatives reply number 42. 21 December 2003.http://www.shugiin.go.jp/itdb_shitsumon.nsf/html/shitsumon/b155042.htm.

- Human Rights Watch. 2000. Owed Justice: Thai Women Trafficked into Debt Bondage in Japan. September 2000.

http://www.hrw.org/reports/2000/japan/. - Immigration Bureau. 2005. The Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act: FY 2005 Amendment, 2005.

- Immigration Bureau. Website. “Deportation and Departure Order System”.http://www.immi-moj.go.jp/english/tetuduki/index.html. Last accessed in November 20, 2012.

- Immigration Bureau. Website. “Deportation Procedure” (chart)http://www.immi-moj.go.jp/english/tetuduki/taikyo/taikyo_flow.pdf. Last accessed in November 20, 2012.

- Immigration Bureau. 2012. Response to the inquiry from Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan. 20 November, 2012.

- Immigration Bureau. 2005. Immigration Control Report 2005. Ministry of Justice.

http://www.moj.go.jp/NYUKAN/nyukan46.html. - Immigration Bureau. 2006. Immigration Control Report 2006. Ministry of Justice. 2006.

http://www.moj.go.jp/NYUKAN/nyukan54.html. - Japan Federation of Bar Association (JFBA). 2009. The Japan Federation of Bar Associations’ Report on the Japanese Government’s Third Report on

The Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Initial Reports onOPAC & OPSC.http://www.nichibenren.or.jp/library/ja/kokusai/humanrights_library/treaty/data/child_report_3_en.pdf. - Japan Federation of Bar Association (JFBA). 2012. Statement by the chairperson of Japan Federation of Bar Association on the commencement of Residence Card system and Residential Basic Book for Foreign residents. Website (in Japanese),http://www.nichibenren.or.jp/activity/document/statement/year/2012/120709.html.

- Japan Federation of Bar Associations. 2007. Japan Federation of Bar Associations Report on the Japanese Government’s Implementation of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel. Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. January 18, 2007.

- Japan Lawyers Nssociation for Refugees (JLNR). 2006. Statement on 4 October, 2006. http://www.jlnr.jp/statements/20061004.pdf.

- Japan Lawyers Network for Refugees (JLNR). 2007.“Jyoriku boushi shisetsu Unyo kanri yoko” (Guidelines for management of landing prevention facilities). July 2007.http://www.jlnr.jp/guidance_and_instructions/guidelines_borderadmini.pdf.

- Japanese Ministry of Finance (MoF). 2006. Reflection of Budget Execution Audit FY2006.http://www.mof.go.jp/budget/topics/budget_execution_audit/fy2006/hanei/tyousa_b.pdf.

- Japanese Ministry of Justice. 2006. Forty-fifth Annual Statistical Report of Emigration and Immigration Management (Eighteenth Year of Heisei Era), National Printing Bureau, 2006.

- Japanese Ministry of Justice. “Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act of 1951.” Japanese Ministry of Justice,http://www.moj.go.jp/ENGLISH/information/icrr-01.html.

- Japanese Ministry of Justice (MoJ). 2010. Basic Plan for Immigration Control, 4th edition, March 2010. http://www.immi-moj.go.jp/seisaku/keikaku_101006_honbun.pdf.

- Japanese Ministry of Justice (MoJ). 2012. Summary of measures taken in response to opinion made by Immigration Detention Facilities Visiting Committees. June 2012.

http://www.moj.go.jp/content/000103146.pdf

http://www.moj.go.jp/content/000103147.pdf. - Japanese Ministry of Justice (MoJ). 2009. 2009 Immigration Control Report.

http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyukan_nyukan91.html. - Japanese Ministry of Justice (MoJ). 2011. 2011 Immigration Control Report.http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyuukokukanri06_00018.html.

- Japanese Ministry of Justice (MoJ), 2012. 2012 Immigration Control Report.

http://www.moj.go.jp/nyuukokukanri/kouhou/nyuukokukanri06_00025.html. - Japanese Ministry of Justice (MoJ).2009. Website, “Changes to the Immigration Control Act”. http://www.immi-moj.go.jp/english/newimmiact/newimmiact_english.html.

- Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication: Statistics Bureau. “Statistics on deportation procedure: number of application and processed cases by regional immigration bureaus” (in Japanese). See File 11-00-31.http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/List.do?lid=000001089429.

- Kaneko, Mai. 2003 “Beyond “Seclusionist” Japan: Evaluating the Free Afghans/Refugee Law Reform Campaign after September 11,” Refugee, Vol. 21 (3), 2003.

https://www.library.yorku.ca/ojs/index.php/refuge/article/viewFile/7078/6229. - Kashiwazaki, Chikako and Tsuneo Akaha. 2006. “Japanese Immigration Policy: Responding to Conflicting Pressures,” Migration Information Source, 2006,

http://www.migrationinformation.org/Profiles/display.cfm?ID=487. - Keidanren (Japan Business Federation). 2010. “Aiming more Affluent and Energetic Society: Keidanren Growth Strategy 2010.”http://www.keidanren.or.jp/japanese/policy/2010/028/honbun.pdf.

- Keidanren (Japan Business Federation). 2011. “Report on Japan’s Industrial Competitiveness.”http://www.keidanren.or.jp/japanese/policy/2011/064/honbun.pdf.

- Lee, June JH. 2005. “Human Trafficking in East Asia: Current Trends, Data Collection, and Knowledge Gaps,” International Migration, Vol. 43 (1/2), 2005.

- Merviö, Mika. 2003. “Koreans in Japan: A Research Update.” Paper presented at the conference Cross-border Human Flows in Northeast Asia: A Human Security Perspective, United Nations University, Tokyo, October 7, 2003.

http://gsti.miis.edu/CEAS-PUB/2003_Mervio.pdf. - Ministerial Meeting Concerning Measures Against Crimes Japan. 2009. “Japan’s 2009 Action Plan to Combat Trafficking in Persons.” December 2009. http://www.mofa.go.jp/j_info/visit/visa/topics/pdfs/actionplan0912.pdf.

- Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. 2006. “Invisible Immigrants: Undocumented Migration and Border Controls in Early Postwar Japan,” Japan Focus, August 31, 2006,

http://japanfocus.org/products/details/2210. - NGO Committee against the introduction of "Zairyu Card (resident card)" system. 2009. Website. 8 July, 2009 (in Japanese).http://www.repacp.org/aacp1.0/Statement.php?d=20090708.

- Noguchi, Sharon. 2007. “Finding Home: Immigrant Life in Japan,” Japan Focus, February 9, 2007, http://japanfocus.org/products/details/2349.

- Protection Project. 2003. Human Rights Report on Trafficking in Persons, Protection Project, 2003.

- Shoji, Hiroka (Amnesty International-Japan). 2012. Interview with Yuki Kobayashi (Global Detention Project). Geneva, Switzerland. November 12, 2012.

- Shoji, Hiroka. 2010. “Nyukoku Kanri-kyoku Shuyo Shisetsu: Naze Bouryoku-koui ha Tomaranaika (Immigration Detention Facilities: Why there are persistent violence)”. Sekai, September, 2010. pp.29-32.

- Shoji, Hiroka. 2009. “Nyukan Shuyo to Shimin Shakai no Yakuwari (Immigration Detention and the Role of Civil Society)”. M-Net, No. 154. Novemeber 2012. pp.3-5.

Ministerial Meeting Concerning Measures Against Crimes Japan, “Japan’s 2009 Action Plan to Combat Trafficking in Persons”, December 2004.http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/i_crime/people/action.pdf. - Tanaka, Kimiko.(Ushiku-no-Kai). 2013. Interview with Yuki Kobayashi (Global Detention Project). Geneva, Switzerland. November 12, 2012.

- UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). 2010. UN migrants rights expert urges Japan to increase protection of migrants, UNOHCHR Press Release, 31 March 2010.http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=9950&LangID=E.

- UN Committee Against Torture. Consideration of Reports Submitted by State Parties Under Article 19 of the Convention: Initial Report of States parties due in 1996; Japan [20 December 2005], CAT/C/JPN/1*, 21 March 2007.

- UN Human Rights Committee. 2006. Consideration of Reports submitted by States Parties under Article 40 of the covenant, Fifth Periodic reports of state parties, Japan. 2006. CCPR/C/JPN/5.http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/hrcs92.htm.

- UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance. 2006. Mission to Japan, E/CN.4/2006/16/Add.2, 24 January 2006.

- UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants (SRHRM). 2006. “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, Jorge G. Bustamante Addendum.” E/CN.4/2006/73/Add.1. 2006.

- UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants (SRHRM). 2011. Mission to Japan. A/HRC/17/33/Add.3. 2011.

- U.S. Department of State. 2012. “Trafficking in Persons Report 2012”.http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2012/.

- Van Arsdol, Maurice, GDC Guarin and Stephen Lam. 2002. “Migration Patterns in Northeast Asia: An Update.” Paper presented at the seminar Human Flows across National Borders in Northeast Asia, United Nations University, Tokyo, November 20–21, 2002.

http://gsti.miis.edu/CEAS-PUB/2003_Mervio.pdf. - 日本政府の「人身取引対策行動計画」1策定から3年 ~事態の変化を検証するhttp://www.hurights.or.jp/japan/aside/human-rights-of-migrants/2007/12/13.html.

- 法務省組織令 Cabinet Order on Organization of Ministry of Justice. 2000. Number 248, June 7, 2000.

- 法務省設置法, Act for Establishment of the Ministry of Justice.

- 出入国管理及び難民認定法 Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act.

- 出入国管理及び難民認定法施行規則 Ordinance for Enforcement of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act.

- 東京入国管理局羽田空港支局 業務概況書Haneda Airport district immigration office. 2011. Review of operations November 2011.

- 上陸防止施設管理運用要領http://www.jlnr.jp/guidance_and_instructions/guidelines_borderadmini.pdf.

DETENTION STATISTICS

Reported Detainee Population (Day)

DETAINEE DATA

DETENTION CAPACITY

ALTERNATIVES TO DETENTION

ADDITIONAL ENFORCEMENT DATA

PRISON DATA

POPULATION DATA

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DATA & POLLS

LEGAL & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

Does the Country Have Specific Laws that Provide for Migration-Related Detention?

Do Migration Detainees Have Constitutional Guarantees?

GROUNDS FOR DETENTION

Criminal Penalties for Immigration-Related Violations

DETENTION INSTITUTIONS

PROCEDURAL STANDARDS & SAFEGUARDS

COVID-19 DATA

TRANSPARENCY

MONITORING

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MONITORING BODIES

NATIONAL PREVENTIVE MECHANISMS (OPTIONAL PROTOCOL TO UN CONVENTION AGAINST TORTURE)

NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS (NGOS)

GOVERNMENTAL MONITORING BODIES

INTERNATIONAL DETENTION MONITORING

INTERNATIONAL TREATIES & TREATY BODIES

International Treaties Ratified

Ratio of relevant international treaties ratified

Relevant Recommendations or Observations Issued by Treaty Bodies

fourteenth periodic reports of Japan"

23. Please provide information on measures taken to ensure equal access to justice for non-citizens, ethnic minorities, Indigenous Peoples and stateless persons, including the availability of interpretation services and public legal aid. Please include statistics on complaints and cases involving allegations of racial discrimination decided by courts or administrative bodies, and on remedies granted to victims. Please also indicate whether asylum-seekers and migrants held in immigration detention or on provisional release have effective access to judicial review and to independent complaint mechanisms.

46. Please clarify whether the Immigration Services Agency provides administrative

remedy or offers appeals procedures for foreign nationals alleging discrimination in

immigration detention, deportation or the determination of refugee status, and indicate the number and outcomes of such appeals.

32.The Committee notes the responses of the State party in regard to the treatment of aliens, including refugees and asylum-seekers, and welcomes the information on the development of an improvement plan regarding treatment in detention facilities, and the revision of the deportation procedure to establish that the scheduled date of deportation is at least two months after the delivery of notification on the decision. The Committee notes with interest that the State party is considering the possibility of amending the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act to stipulate alternatives to detention and introduce a system for recognizing eligibility for complementary protection. Furthermore, the Committee welcomes the State party’s willingness to consider measures to avoid long-term detention. It remains concerned, however, at the alarming reports of suffering due to poor health conditions in immigration detention facilities, including those resulting in the death of three detainees between 2017 and 2021, and of the precarious situations of karihomensha, individuals who have lost their resident status or visas and are on “provisional release”, without options to work or obtain revenue. The Committee is also concerned by reports of the low rate of refugee recognition (arts. 7, 9, 10 and 13)

...

33. Taking into consideration the Committee ’ s previous recommendations, the State party should:

(a) Promptly adopt comprehensive asylum legislation, in accordance with international standards;

(b) Take all appropriate measures to guarantee that immigrants are not subjected to ill-treatment, including through the development of an improvement plan, in accordance with international standards, regarding treatment in detention facilities, including access to adequate medical assistance;

(c) Provide the support necessary to immigrants who are on “ provisional release ” and consider establishing opportunities for them to engage in income-generating activities;

(d) Ensure that the principle of non-refoulement is respected in practice and that all persons applying for international protection are given access to an independent judicial appeals mechanism with suspensive effect against negative decisions;

(e) Provide alternatives to administrative detention, take steps to introduce a maximum period of immigration detention, and take measures to ensure that detention is resorted to for the shortest appropriate period and only if the existing alternatives to administrative detention have been duly considered, and that immigrants are able to effectively bring proceedings before a court that will decide on the lawfulness of their detention;

(f) Guarantee adequate training of border-guard officials and immigration personnel to ensure full respect for the rights of asylum-seekers under the Covenant and other applicable international standards.

(a) Ensure that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration in all decisions relating to children and that the principle of non- refoulement is upheld ;

(b) Establish a legal framework to prevent asylum-seeking parents being detained and separated from their children;

(c) Take immediate measures, including through the establishment of a formal mechanism, to prevent the detention of unaccompanied or separated asylum-seeking or migrant children, ensure the immediate release of all such children from immigration detention facilities and provide them with shelter, appropriate care and access to education;

(d) Develop campaigns to counter hate speech against asylum seekers and refugees, particularly children."

33.The Committee is concerned at the lack of remedies available in line with article 17 (2) (f) of the Convention to challenge the lawfulness of deprivation of liberty, including that of persons in medical institutions and immigration detention facilities. The Committee takes note of the existence of the Habeas Corpus Act to challenge the lawfulness of a detention. However, it is concerned at the obstacles to the use of this remedy contained in the Habeas Corpus Rules, in particular rule 4, and at the fact that a habeas corpus request can only be made by the person deprived of liberty and his or her counsel (arts. 17 and 22).

...

34. The Committee recommends that the State party adopt the necessary measures to establish that the right to apply for habeas corpus may not be restricted under any circumstances and guarantee that any person with a legitimate interest may initiate the procedure, irrespective of the place of deprivation of liberty.

...

36. Recalling its general recommendation No. 22 (1996) on article 5 of the Convention on refugees and displaced persons, the Committee recommends that the State party ensure that all applications for asylum status receive due consideration. The Committee also recommends that the State party introduce a maximum period for immigration detention, and reiterates its previous recommendation (CERD/C/JPN/CO/7-9, para. 23) that detention of asylum seekers should only be used as a measure of last resort and for the shortest possible period of time, and that efforts should be made to prioritize alternative measures to detention. The Committee recommends that the State party allow applicants for refugee status to work, six months after they have submitted their applications.

...

39. Bearing in mind the indivisibility of all human rights, the Committee urges the State party to consider ratifying those international human rights instruments that it has not yet ratified, in particular treaties with provisions that have direct relevance to communities that may be subjected to racial discrimination, including the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty; the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families; the International Labour Organization (ILO) Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111); and the ILO Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169).

(a) Promote non-discrimination and understanding among its local authorities and communities with regard to refugees and asylum seekers;

(b) Guarantee that detention of asylum seekers is used only as a measure of last resort and for the short est possible period. The State party should give priority to alternative measures to detention, as provided for in its legislation;

(c) Develop a statelessness determination procedure to adequately ensure the identification and protection of stateless persons.

The State party should also consider acceding to the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and to the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness.

19 (c):Take measures to ensure that detention is resorted to for the shortest appropriate period and only if the existing alternatives to administrative detention have been duly considered and that immigrants are able to bring proceedings before a court that will decide on the lawfulness of their detention.

19. The Committee expresses concern about reported cases of ill-treatment during deportations, which resulted in the death of a person in 2010. The Committee is also concerned that, despite the amendment to the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, the principle of non-refoulement is not implemented effectively in practice. The Committee is further concerned at the lack of an independent appeal mechanism with suspensive effect against negative decisions on asylum, as well as at the prolonged periods of administrative detention without adequate giving of reasons and without independent review of the detention decision (arts. 2, 7, 9 and 13).

The State party should:

(a) Take all appropriate measures to guarantee that immigrants are not

subject to ill-treatment during their deportation;

(b) Ensure that all persons applying for international protection are given

access to fair procedures for determination and for protection against refoulement and have access to an independent appeal mechanism with suspensive effect against negative decisions;

(c) Take measures to ensure that detention is resorted to for the shortest

appropriate period and only if the existing alternatives to administrative detention have been duly considered and that immigrants are able to bring proceedings before a court that will decide on the lawfulness of their detention.

[...]

The State party should ensure that all measures and practices relating to the detention and deportation of immigrants

are in fullconformity with article 3 of the Convention. In particular, the State party should expressly prohibit deportation

to countries where there are substantial grounds for believing that the individuals to be deportedwould be in danger of

being subjected to torture, and should establish an independent body to reviewasylumapplications. The State party

should ensure due process in asylumapplications and deportation proceedings and should establishwithout delay an

independent authority to reviewcomplaints about treatment in immigration detention facilities. The State party should

establish limits to the length of the detention period for persons awaiting deportation, in particularfor vulnerable groups,

andmake publicinformation concerning the requirement for detention afterthe issuance of a written deportation order.

> UN Special Procedures

Visits by Special Procedures of the UN Human Rights Council

Relevant Recommendations or Observations by UN Special Procedures

83. The Working Group expresses its serious concern over the compatibility of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act of Japan with the country’s obligations under international law and the Covenant in particular. The Working Group urges the Government to promptly review this Act to ensure that it duly reflects the right to personal liberty of everyone.

[...]

86. In the present case, Messrs. Yengin and Safari Diman were repeatedly detained by the Japanese authorities without any reasons being provided for their detention. It is clear to the Working Group that this could not have been in pursuance to any of the legitimate aims such as to document their entry or to verify their identities. In fact, the Working Group is convinced that Messrs. Yengin and Safari Diman were detained purely for their legitimate and peaceful exercise of their right to seek asylum as enshrined in article 14 of the Universal Declaration. Their detention was therefore arbitrary and falls under category II.

[...]

92. Consequently, the Working Group finds that Messrs. Yengin and Safari Diman were subjected to indefinite immigration detention, which is contrary to the obligations Japan has undertaken under international law, particularly article 9 of the Covenant. The Working Group therefore concludes that Messrs. Yengin and Safari Diman have been denied an effective remedy to challenge their detention in breach of articles 8 and 9 of the Universal Declaration and articles 2 (3) and 9 of the Covenant and that their detention is therefore arbitrary, falling under category IV.

[...]

93. Although the source has not made submissions under category V, the Working Group considers that the submissions warrant examination under this category as well.

[...]

100. In the light of the foregoing, the Working Group renders the following opinion:

The deprivation of liberty of Deniz Yengin and Heydar Safari Diman, being in contravention of articles 2, 3, 8, 9 and 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and articles 2, 9 and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights, is arbitrary and falls within categories I, II, IV and V.

> UN Universal Periodic Review

Relevant Recommendations or Observations from the UN Universal Periodic Review

70. The same Committee was concerned by the very low acceptance rate of asylum

applications (19 out of 11,000 applications) and by the detention of asylum-seekers for

indeterminate periods, without establishing fixed time limits for their detention. It

recommended that Japan ensure that all applications for asylum status received due

consideration. It also recommended introducing a maximum period for immigration

detention; using detention of asylum-seekers as a measure of last resort only and for the

shortest possible period of time; and prioritizing alternative measures.100 UNHCR made

similar recommendations, including establishing mandatory and independent detention

reviews that included judicial safeguards.101

71. The Committee on the Rights of the Child recommended that Japan establish a legal

framework to prevent asylum-seeking parents being detained and separated from their

children; prevent the detention of unaccompanied or separated asylum-seeking or migrant

children, ensure their immediate release and provide them with shelter, appropriate care and

access to education; and develop campaigns to counter hate speech against asylum-seekers

and refugees, particularly children.

immigration detention facilities and avoid unnecessary long-term detention of immigrants by defining detention criteria, introducing judicial review, setting a limit on the detention period and granting provisional release (Kingdom of the Netherlands);

Seriously consider the long-term detention of foreign nationals at immigration centres and prevent the authorities from controlling the complaint process at immigration detention centres (Islamic Republic of Iran); Ensure that the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act

enshrines the protection of all migrants so that they have access to effective procedural safeguards and can challenge the grounds or legality of their detention in court (Spain); Increase protection of migrants’ rights, including by bringing its deportation policy into line with international human rights law and limiting immigration administrative detention (Brazil); Establish a maximum term for the detention of immigrants, using it as a measure of last resort, and ensure that all asylum applications receive prompt and adequate treatment (Colombia);

> Global Compact for Migration (GCM)

> Global Compact on Refugees (GCR)

REGIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MECHANISMS

HEALTH CARE PROVISION

COVID-19

Country Updates

Government Agencies

Immigration Bureau of Japan, http://www.immi-moj.go.jp/english/

Ministry of Justice, https://www.moj.go.jp/EN/

International Organisations

International Labour Organization: Office in Japan, http://www.ilo.org/public/english/region/asro/tokyo/

International Organisation for Migration (IOM) - Japan - Country Information, http://www.iom.int/countries/japan/general-information

IOM - Japan (Japanese), http://www.iomjapan.org/

UNHCR - Japan - Country Information, https://www.unhcr.org/where-we-work/countries/japan

NGO & Research Institutions

Amnesty International Japan, https://www.amnesty.org/en/

Asia Pacific Human Rights Information Centre (HURIGHTS Osaka), https://www.hurights.or.jp/english/

Global Migration and Japan, www.kisc.meiji.ac.jp/~yamawaki/gmj/

International Movement Against All Forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR), http://imadr.org

Japan Association for Refugees, http://www.refugee.or.jp/

Japan Civil Liberties Union (JCLU), https://jclu.org/english/

Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, https://www.jil.go.jp/english/

Japan Network Against Trafficking in Person,https://www.jnatip.net/

Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan, https://migrants.jp/english.html