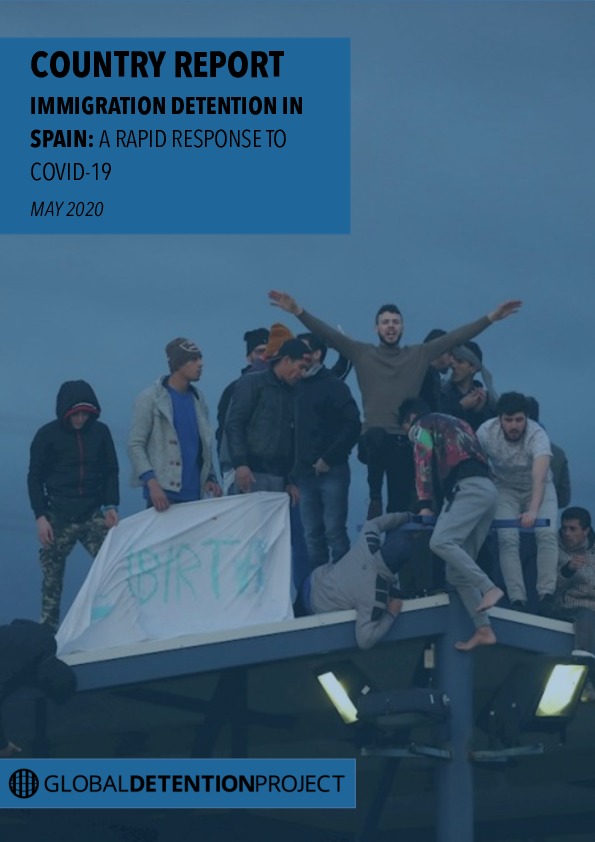

The deaths of 37 migrants and asylum seekers in late June along the border fence separating the Spanish enclave of Melilla from Morocco have spurred numerous protests across cities in both countries. Thousands of protestors gathered in Barcelona, Malaga, Vigo, San Sebastian, and Melilla to denounce migration policies as well as the militarisation of Spain’s […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

Spain’s detention and removal operations have begun to return to normal operations after major disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which had spurred the country to temporarily close all its detention centres shortly after onset of the pandemic in early 2020. Despite this, COVID continues to wreak havoc in detention centres even as the country […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

Shortly after the onset of the first wave of COVID-19 in early 2020, Spain began emptying its immigration detention centres – Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros (CIEs) – and by 6 May 2020, authorities had temporarily closed them all (see 15 May 2020 Spain update on this platform). This development was welcomed by human rights […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

During the past year Spain’s Canary Islands, situated off the western coast of North Africa, have witnessed a surge in migrant and asylum-seeker arrivals, a recurring situation that emerges when migration routes elsewhere in Africa are blocked. According to the Spanish Interior Ministry, the number of maritime arrivals during 2020 was eight times higher than […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

There have been a number of judicial decisions in Spain in recent weeks that could have crucial impacts on how migrants and asylum seekers are treated, in particular with respect to Covid-related border controls. In one case from November, Spain’s Constitutional Court found that a provision in the country’s controversial Citizen Security Law allowing push […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

In October, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) issued a ruling on a deportation case in Spain that would limit the country’s ability to enforce removal decisions in certain cases based on provisions of the EU Return Directive. The court in Spain’s Castilla-La Mancha region had asked the CJEU whether authorities could […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

While migrant arrivals to Mainland Spain have decreased this year, the number of migrants and asylum seekers arriving in the Canary Islands has significantly increased. According to UNHCR, as of 18 October 24,259 arrivals had been registered in Spain, of whom 9,199 were registered in the Canary Islands. (In all of 2019, 2,698 migrants arrived […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

In Melilla, more than 1,400 refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants–including 150 women and 143 children–have again been confined in the enclave’s overcrowded CETI (Center for Temporary Stay of Immigrants) following a Covid-19 diagnosis. On 21 August, the facility was closed with no-one permitted to enter or exit–despite a judge’s decision on 24 August to overturn […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

Responding to the Global Detention Project’s Covid-19 survey, the Permanent Observatory for Immigration, part of the Ministry of Labour and Immigration, and acting as European Migration Network (EMN) contact, reported that no moratorium on new immigration detention orders was established, but that immigration detention is no longer justifiable in law as there are no reasonable […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

After the release of immigration detainees from detention centres (Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros or CIEs), there has been considerable discussion on the future of the country’s detention policies. The Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos de Andalucía (APDH) reports that “since CIEs have been closed and detainees released, no catastrophe has ensued” and the organisation urged […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

Spain’s decision to temporarily shut its “foreigner internment centres” (CIEs)–which were empty as of 6 May–in response to the Covid-19 crisis has raised questions about the treatment of released detainees. In late March the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security, and Migration announced that it would work in coordination with the Immigration and Border police to […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

For the first time in its history, Spain reported that its long-term immigration detention centres–Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros–were emptied, a result of measures implemented in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The final four detainees were released on 5-6 May from the Algeciras detention centre. The Interior Ministry had been progressively releasing detainees for the […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

Spain’s Defensor del Pueblo (Ombudsman) released a statement on 17 April that expressed concern about the overpopulation at detention centres in Ceuta and Melilla (called “Centros de estancia temporal para inmigrantes”). The Ombudsman highlighted the plight of children at these facilities, as reports indicate that a large number of them are held there. The Ombudsman […]

Spain: Covid-19 and Detention

Spain was one of the first countries in Europe to release immigration detainees amidst the Covid-19 crisis, to date. However the GDP has found little information detailing the situation that released detainees now face, or the level of support that they are receiving. As flights were grounded and movement halted, it was quickly apparent that […]

The joint flight: preparation, execution and handover in Spain ( from report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture 2016 visit to Spain)

The joint flight: preparation, execution and handover. (Read full CPT report) 9. The practice of removal of foreign nationals is a frequent and widespread practicethroughout Europe. For Spain, removal operations to Latin America in particular are commonplace.In the CPT’s experience, removal of foreign nationals entails a manifest risk of inhuman anddegrading treatment (during preparations for […]

Last updated: May 2020

Immigration Detention in Spain

- Key Findings

- Introduction

- Laws, Policies, Practices

- Detention Infrastructure

- PDF version of 2020 Profile

- PDF version of 2016 Profile

- PDF version of 2013 Profile

KEY FINDINGS

- Spain was one of the first countries in Europe to release detainees in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, however concerns were raised about the treatment of people after being released and whether adequate safeguards were provided.

- While authorities promptly took steps to protect immigration detainees in mainland Spain, similar measures were reportedly not forthcoming in the country’s North African enclaves.

- There are long-standing concerns that authorities routinely fail to consider all criteria before imposing detention measures.

- People arriving in Spain by sea are automatically detained in police stations for up to 72 hours.

- Reports suggest that authorities often fail to investigate complaints of ill-treatment in detention facilities, and there are cases in which people who have lodged complaints have been summarily expelled.

- Less than 50 percent of detainees are eventually deported, underscoring the routine practice of detaining non-deportable people and raising questions about whether detention is used as an arbitrary form of punishment.

- Spanish law guarantees civil society access to places of detention, but NGOs claim that they are often denied access.

1. INTRODUCTION

As countries across the eastern and central Mediterranean have ramped up controls along migratory routes, Spain has become an increasingly important entry point into Europe. While Frontex, the EU’s border agency, reported that by 2018 overall detections of unauthorised border-crossings into the EU had reached their lowest level in five years (“92 percent below the peak of the migratory crisis in 2015,”) between 2017 and 2018, Spain experienced a twofold increase in entries.[1] By 2019, these arrival trends started to decline, from 65,400[2] in 2018 to 32,500[3] in 2019; however, asylum requests skyrocketed from 54,050 in 2018[4] to 117,800 in 2019.[5]

Spain’s responses to these pressures have fluctuated. In June 2018, when Malta and Italy refused to allow the Aquarius—a rescue ship carrying more than 600 migrants and asylum seekers—to dock, Spain offered a safe harbour to the boat and its passengers.[6] Less than a year later, in early 2019, the Spanish government proposed a plan to reduce irregular immigration by 50 percent by ending active rescue patrols along the Mediterranean coast and prohibiting NGO rescue boats from docking.[7] Although the country’s Interior Ministry walked back this proposal, the government unveiled a new strategy ahead of the 2019 EU election aimed at reducing arrivals, including by tasking the country’s military police—the Guardia Civil—with control of sea rescue and increasingly relying upon Morocco’s coastguard to intercept vessels.[8]

The call for increased reliance on Morocco to interdict migrant vessels is part of Spain’s broader efforts to “externalise” immigration controls to nearby countries in Africa, which date back more than a decade. This has included EU and Frontex assistance in interdicting boats en route to the Canary Islands, financing detention operations in Mauritania, and facilitating cooperation between police forces from Senegal to Morocco on migration control.[9] Critics have argued that increased efforts by Spain and the EU to block migratory routes have led to increased rights violations[10] and international human rights bodies have scrutinised Spain’s responsibility for violations that may result from these efforts.[11] (For more on Spain’s history of pushing out its border controls, see 2.18 Externalisation.)

The land borders surrounding Spain’s two enclaves in Morocco, Ceuta and Melilla, have also witnessed violent confrontations for many years, as Spanish and Moroccan police attempt to stop people from crossing into Spanish territory. The deaths of asylum seekers during these confrontations have drawn attention to the practice of summary returns—“hot returns” or “push-backs” (devoluciones en caliente). Controversially, in February 2020 the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruled that Spain had acted lawfully when it summarily deported two people who had tried to scale the border fence in 2014.[12] While the two individuals argued that they were not given the opportunity to explain their circumstances or receive assistance from translators or lawyers, the ECtHR ruled that no violation had occurred. Experts warned that this would set a dangerous precedent, encouraging Spain and other countries to continue summary deportations. The head of the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights commented that “it will be perceived as a carte blanche for violent push-backs everywhere in Europe.”[13]

Conditions in the country’s “Foreigner Internment Centres” (centros de internamiento de extranjeros - CIEs) have long been the subject of scrutiny and criticism.[14] The poor treatment of detainees in some facilities and the perceived inadequacy of detention as a response to migration and refugee challenges have spurred doubts about the need to maintain Spain’s large network of detention centres. Local authorities in several cities—including Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia—have been key supporters of this campaign, resulting in a confluence of agendas between activists and local officials.[15]

In 2018, several episodes—including a series of protests and riots at the Aluche CIE in Madrid, with one in October 2018 leading to the injury of 11 police officers and one detainee—placed the country’s detention estate under intense scrutiny.[16] On the other hand, courts, the Ombudsman (Defensor del Pueblo), and NGOs that monitor places of detention recorded improvements in conditions of detention during this time, including better access to health, asylum processing, and information.[17]

After the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic, Spain was one of the first states in Europe to release immigration detainees. With flights grounded, it was quickly apparent that expulsions would no longer be possible and that many detention orders had thus lost their legal justification, prompting the Spanish Ombudsman to comment on 19 March that in these circumstances, “[immigration detainees] must be released.”[18] By 5 April 2020, there were only 34 persons detained throughout Spain’s CIEs, and as of 21 April the Barcelona, Tenerife, Hoya Fria, Aluche, and Barranco Seco CIE’s were temporarily closed. By 6 May, Spain announced that its CIEs were completely empty.[19]

Although the Spanish government adopted measures on 20 March 2020 to guarantee that migrants and refugees in the country may benefit from the country’s protection system,[20] the GDP found little information detailing the situation that released detainees faced upon release, or the level of support that they received.

Although Spanish authorities took steps to mediate the impact of Covid-19 on immigration detainees in mainland Spain, few measures appear to have been adopted in the country’s North African enclaves. Reports indicated that in Melilla, persons held in temporary detention facilities (Centros de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes – CETIs) faced overcrowding, a lack of protective measures, and insufficient information from Spanish authorities.[21] Spain’s Defensor del Pueblo (Ombudsman) released a statement detailing concerns for the wellbeing of those held inside CETIs—particularly children—and urged authorities to transfer persons from such facilities to the Spanish mainland.[22]

2. LAWS, POLICIES, PRACTICES

2.1 Key norms. The Spanish Constitution provides the right to liberty and protection against arbitrary detention (Article 17), including guarantees of due process in Articles 24 and 25.

Legal norms relevant to immigration-related detention are provided in several sources:

- the Organic Law 4/2000 of 11 January, on the rights and liberties of foreign persons in Spain and their social integration (Ley Orgánica 4/2000, de 11 de enero, sobre derechos y libertades de los extranjeros en España y su integración social) (LOEXIS),[23] as amended by Organic Law 2/2009 of 11 December (Aliens Act or LOEX);

- the Royal Decree 557/2011 of 20 April (RLOEX), approving the Regulation of the Organic Law 4/2000;

- the Royal Decree 162/2014 of 14 March, approving the operating regulation and internal regime of immigration detention centres;

- Circular 6/2014 establishing certain criteria for detention in a CIE to proceed;

- Asylum Law 12/2009 of 30 October, regulating the right to asylum and subsidiary protection, as amended by Organic Law 2/2014 of 25 March;

- the Framework Protocol for the Protection of Victims of Human Trafficking of 28 October 2011 (FPHT);

- the Framework Protocol on proceedings regarding unaccompanied foreign minors (MENA) of October 2014;

- the Penal Code.

Organic Law 4/2015 on the protection of citizen security incorporates an additional provision to Organic Law 4/2000, establishing a special regime for Ceuta and Melilla and authorising summary returns to prevent irregular entry to these territories. This regime of exception has been criticised by the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights for its lack of procedural standards to protect asylum seekers. (France makes similar exceptions to it migration law in its overseas territory of Mayotte.)

2.2 Covid-19 response. On 6 May 2020, for the first time since they were created, Spain’s CIEs were reported as being empty as a result of releases from detention in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.[24] The organisation “Plataforma CIE NO Madrid” celebrated the news stating: “Today is a day that we will not forget, nor will we forget the human rights violations, deaths, humiliating treatment or torture that has occurred within the walls of CIEs ever since they were created.”[25] The Campana Estatal por el Cierre de los CIE (Campaign to Close Detention Centres) also welcomed the news but cautioned that detainees were left without support or a place of residence, and they were not referred to reception centres.[26]

Shortly after Spain declared, on 14 March 20202, a state of emergency and placed the country under lockdown to stem the pandemic, the Spanish Ombudsman called for the release of immigration detainees.[27] Member organisations of the “Campana Estatal por el Cierre de los CIE” (Campaign to Close Detention Centres) also urged the government to close immigration detention centres as returns could no longer be undertaken.[28] The Interior Ministry advised that detainees who cannot be deported or who have been detained longer than the maximum period (60 days), should be released.[29] (The move was is in line with Article 15(4) of the EU Returns Directive, which states that “when it appears that a reasonable prospect of removal no longer exists… detention ceases to be justified and the person concerned shall be released immediately.”)

Within a month, most of Spain’s immigration detention detainees had been released. The Valencia CIE was the first to release detainees, on 16 March 2020,[30] and by 5 April there were only 34 people detained across Spain’s seven CIE’s. Five CIE’s including, the Barcelona; Tenerife; Hoya Fria; Aluche CIE and Barranco Seco CIE’s, were temporarily shut and detainees released or transferred to other facilities.[31] By 6 May, Spain had announced that all of its CIEs had been completely emptied.[32]

As one commentator wrote, the Spanish authorities “recognized what activists have been saying all along—health and legal issues make the system untenable. With poor sanitary conditions and the inability to socially distance, immigration detention centres are perfect virus incubators. The risk to detainees, staff and the wider public is obvious.”[33]

2.3 Grounds for detention. Under Article 1 of Royal Decree 162/2014, the purpose of detention (the specific term used is “internment”) in CIEs is to guarantee an individual’s deportation. Deportation can be an administrative sanction for violating immigration law, a consequence of an entry refusal, a consequence of having been convicted of a crime, or as a substitution for a criminal conviction. The Aliens Act uses different expressions to refer to different types of deportation: expulsion, refusal of entry, and devolution—however all types of deportation may lead to administrative detention.

Detention to ensure expulsion can be ordered in the following cases: (1) when an individual allegedly violates Articles 53 and 54 of the Aliens Act, including by being on Spanish territory without proper authorisation, poses a threat to public order, or participates (for-profit) in clandestine migration; or (2) when the non-citizen is due to be expelled having been convicted of a criminal offence in a case where the law either provides for expulsion as a substitute for prison sentences exceeding one year (and up to six years) or the payment of a fine (Article 57(2),(4) and (7) and Article 89 of the Penal Code). Before authorities issue a detention order, criteria such as the foreigner’s personal, social, and familial circumstances and the feasibility of executing the expulsion must be assessed (Circular 6/2014). However, according to the Jesuit Migrant Service (JRS) Spain, such assessments are rarely undertaken.[34]

Reportedly, in 2017 many persons were detained in a way that violated fundamental guarantees—specifically, a lack of individualised assessments of the necessity and proportionality of detention. In Motril, groups of newly arrived migrants were given collective detention orders for removal purposes. These were upheld by the Provincial Court of Granada.

In 2018, this situation appeared to somewhat improve following the creation of CATEs (temporary reception centres - Centros de Acogida Temporal de Extranjeros), where international protection needs are carried out.[35] However, reports suggest that—in Malaga at least—Moroccan and Algerian nationals continued to be automatically detained in police stations and subsequently deported, while persons of sub-Saharan or Asian origin were hosted in CATEs—prompting concerns that the necessity and proportionality of detention continues to be insufficiently individually assessed.[36] (This systematic discrimination was noted by the Ombudsman during his visits to police stations in Algeciras and Malaga, prompting him to recommend that humanitarian assistance facilities be used for vulnerable persons, irrespective of their nationality.[37])

When a foreigner attempts to enter Spanish territory without the required documentation, authorities will deny entrance and order their “return” (devolución). If return cannot be executed within 72 hours, the border control authority must refer the situation to a judge who will decide on detention (Article 60(1)). Likewise, if a non-citizen violates a re-entry ban, authorities are to execute the return; if it cannot be executed within 72 hours, the authority must refer the situation to a judge who will decide on detention (Article 58(6)).

When foreigners with criminal records are issued deportation orders, a hybrid combination of administrative measures under the Aliens Act and Penal Code provisions are triggered. Authorities refer to these as “qualified expulsions.” Questions remain, however, as “qualified expulsions” are not defined in law, and government statistics on “expulsiones cualificadas” seem to include “administrative” expulsions under immigration law.[38] In addition, “qualified expulsions” may include persons only “known to the police,” further blurring the lines. In 2012, in an address to Congress, the Interior Ministry referred to the high percentage of persons with criminal records in CIEs (scheduled for “qualified expulsions”) to argue that a substantial number of detainees in CIEs were criminals. A consortium of academics denounced this claim, which they said could be used by the government to justify a punitive environment in CIEs and reduce empathy for detainees.[39]

2.4 Criminalisation. Non-citizens face fines for unauthorised stay in the country, ranging from 501 EUR to 10,000 EUR (Aliens Act, Articles 53 and 55).

2.5 Asylum seekers. Persons in asylum proceedings are not detained; however, those who apply for asylum from detention remain detained while they await the outcome of their application. The procedure for asylum requests submitted from inside CIEs is the “asylum at the border process,” which is intended to be an accelerated procedure (Asylum Law, Article 25.2). The maximum time an asylum seeker can stay in a CIE is eight days—the time needed for procedures at the border to be concluded. In 2017, 1,386 asylum applications were lodged from detention, compared to 761 in 2015, 587 in 2014, and 306 in 2013.[40]

Various shortcomings have been reported regarding applications from detention, specifically the lack of information provided to detainees on the right to seek asylum, the short timeframe of the past procedure applied to asylum claims, and difficulties in obtaining legal assistance.[41] As such, in 2018 the Spanish Ombudsman urged the General Commissariat for Foreigners and Borders to establish a suitable system for registering asylum applications in CIEs in accordance with Spanish law.[42] The National Mechanism for the Prevention of Torture (NPM) observed in 2012 and 2013 that the brochure containing information on international protection in different languages—elaborated by the Office for Asylum and Refuge (OAR)—was missing in the CIEs. In December 2014, a complaint was filed for the expulsion of 20 Malians who were not informed about their right to seek asylum or the procedure for doing so.[43]

In 2015 the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC) asked Spain to avoid the use of detention for asylum seekers, and ensure it is always reasonable, necessary, and proportionate, in light of their individual circumstances.[44]

2.6 Children. Despite not expressly providing for the detention of children, Spanish law still permits accompanied children to be detained in CIEs. While the law provides that unaccompanied children are to be housed in specialised shelters, in practice, some children have been detained as they have been unable to prove their minor status.

According to the Aliens Act, children should not be placed in detention. However, Article 62 bis indirectly provides for the detention of minors as it recognises the right of detainees to “be accompanied by their minor children, provided that the Public Prosecutor gives his agreement to this measure and that the centre includes units that ensure family unity and privacy” (Aliens Act, Article 62 bis.1.i; Royal Decree 162/2014, Article 16.2.k). Nonetheless, in 2015 the Supreme Court revoked Articles 7.3 and 16.2 (k) of the Regulation of Organic Law 4/2000 for failing to comply with the EU Returns Directive, according to which states must provide separate family spaces in CIEs for the detention of minors with their parents, as families were being detained alongside other detainees.[45]

Although the CIE’s Regulation does not explicitly make provisions for the detention of families, Article 57—which deals with disciplinary measures including physical separation from other detainees—appears to imply that mothers with their children can be detained (Article 57(6 (a-d)).

According to Royal Decree 162/2014, specialised care should be provided to vulnerable people—specifically, minors, disabled persons, the elderly, pregnant women, single parents with minors, and survivors of torture, rape, or other serious forms of psychological, physical, or sexual violence (Article 1.4). Circular 6/2014 addresses the situation of vulnerability as a circumstance that should be taken into account when deciding on detention.

Unaccompanied children are housed in children’s shelters (centros de acogida de menores), and autonomous regions are responsible for their protection (Article 35). Some unaccompanied minors have been detained due to a lack of identification proving their minor status. In 2017, 48 minors were identified while in detention.[46] Although the ministry did not stipulate whether they were accompanied, a report by JRS Spain appears to indicate that they were unaccompanied.[47] Throughout 2018, during their regular visits to five CIEs (Algeciras, Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, and Tarifa) JRS Spain staff identified 93 “possible minors” while the government claimed 84 were detained that year.[48] In January 2020, a 16-year-old child was detained in the Valencia CIE even though authorities had proof of his minority through legal documents.[49]

On 22 July 2014, a Framework Protocol for Unaccompanied Foreign Minors was adopted, in cooperation with the Justice, Interior, Employment, Health and Social Services, and Foreign Affairs Ministries as well as the Public Prosecutor, establishing a basis for institutional and administrative coordination with regards to actions in relation to unaccompanied foreign minors. (The protocol is however just a guidance document, as child-related issues fall under the competence of autonomous regions.) The Protocol sets various guidelines on locating and identifying minors, determining their age, and placing them under the care of the social services.[50]

The following year, the UN HRC welcomed the adoption of the protocol but expressed concerns regarding age assessment methods—a practice provided by Article 35.3 of the Aliens Act. Indeed, the provisions of the Protocol do not follow a Spanish Supreme Court judgment, in which it had ruled that when a minor possesses official documentation confirming their minor status, no medical tests should be conducted. Instead, the age assessment process should only proceed if there are reasons to believe that the exhibited documents are unreliable.[51] In practice medical age assessments are employed as a rule rather than exception and are applied even if the individual presents official identity documents or if they manifestly appear to be minors.[52] A top UN official thus stated that the Spanish authorities have continued to challenge unaccompanied minors’ age and argued that the Framework Protocol "seems to contain instructions contrary to the doctrine of Human Rights, the majority opinion of European judges and judgments of the Supreme Court.”[53]

In 2018, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) asked Spain to train border guards and relevant professionals to identify children and their specific protection needs and ensure rapid transfer to adequate reception centres.[54]

In Melilla, numerous reports by observers have highlighted poor conditions in the La Purisima Children’s Centre, despite the fact that the Spanish government spends some five million EUR on the facility each year. Reportedly severely overcrowded, many children do not have access to education and images have shown them sharing mattresses on the floor.[55] In 2018, one of the centre’s staff members was even arrested for stabbing a minor in the facility, while other staff members have been accused of violence and sexual assault.[56] More recently, concerns have been raised regarding the detention of migrant and asylum-seeking children in CETIs in Ceuta and Melilla. In light of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Spanish Ombudsman released a statement in which he drew attention to the wellbeing of children detained in Spain’s North African enclaves and urged the Spanish government to ensure they are relocated to the Spanish mainland. Referring to the centres as overcrowded, he noted that significant numbers of minors are usually held in the facilities.[57]

2.7 Other vulnerable groups. Spanish law does not specifically prohibit the detention of vulnerable groups and only provides that a case-by-case analysis must be undertaken regarding the detention of persons with serious illnesses.

The Aliens Act states that in case of serious illness the judge should assess the risk of detention to both public health and the foreigner (Article 62.1). Circular 6/2014 also refers to the need for judges to take into consideration the physical and psychological condition of the foreigner before deciding on detention. Finally, Royal Decree 162/2014 establishes a medical procedure to identify people with health problems and make arrangements for medical treatment.[58]

According to Article 59 bis of the Aliens Act, necessary measures to identify victims of human trafficking must be adopted by the competent authorities. The 2011 Framework Protocol for Protection of Victims of Human Trafficking contains various provisions for identification and protection of victims of trafficking but fails to clearly provide for the release of victims identified while in detention. External observers have recommended that Spain ensure that “victims who do not testify against perpetrators are not detained or deported.”[59] In practice, identification of victims in CIEs depends upon NGOs and social organisations, as staff in the centres are reportedly not sufficiently trained for the task.[60]

In 2015, the UN Committee against Torture (CAT) urged Spain to urgently reduce overcrowding in temporary migrant holding centres and improve material conditions, particularly for people with special needs—such as single women and women with children.[61]

2.8 Length of detention. Non-citizens can initially be detained for a maximum of 72 hours. Detention for longer than this requires an investigating judge to deliver a judicial order prolonging detention at an officially designated detention centre (Aliens Act, 61.1.d). The prolonged detention can last up to 60 days, and the individual can only be confined as long as necessary to affect expulsion (Article 62.2). Until the country transposed the EU Returns Directive, detainees could be held for up to 40 days. However, Spain is one of the few EU countries to have kept the length of detention well below the 18-month limit allowed in the Returns Directive.[62]

NGOs have highlighted that the average duration of detention has increased in recent years: according to police records, the average stay in detention was 24 days in 2015,[63] while in 2018 it had increased to 26.08 days. However, some CIEs featured longer detention periods in 2018: an average of 34.3 days in Tenerife and 30.59 days in Barcelona.[64]

There have been cases of people being “re-detained” after being released from immigration detention. JRS Spain reported that a quarter of the 346 detainees it visited in Barcelona in 2015 had previously been detained. In 2019, the Interior Ministry’s webpage on CIEs read that after “a maximum duration of 60 days no new detention may be agreed for any of the reasons foreseen in the same case.”[65]

2.9 Procedural standards. The Royal Decree 162/2014 stipulates that no one may be detained unless a decision from the competent judicial authority is provided (Article 2.1). It also stipulates that once a detention order has been issued, the police are responsible for transferring the non-citizen to a detention centre (Article 25.1). According to Police Order INT/28/2013 of 18 January Article 9.4, the Central Unit of Expulsions and Repatriations (Unidad Central de Expulsiones y Repatriaciones) manages all aspects of expulsions, the supervision and coordination of CIEs, and the information flow with penal institutions in relation to the release of foreign prisoners.

The Royal Decree provides various rights to detainees, including the right to be informed about their situation (Article 29); and the right to have a designated person in Spain, their lawyer, and their consulate informed about their detention (Article 31). Detainees may also be assisted by a lawyer and interpreter; contact NGOs and national and international organisations; and file complaints and petitions in defence of their rights before the Director of the CIE, the administrative and juridical competent organs, the Public Prosecutor, and the Ombudsman (Aliens Act, Article 62 bis and Royal Decree 162/2014, Articles 16 and 19). Any complaints or petitions will be presented to the director of the centre who will respond or redirect them to the appropriate authority.

According to various civil society sources, in reality detainees often lack information about their legal information, the rights they are entitled to, and the date and details of expulsion – and these are the source of most complaints amongst detainees.[66] Lack of information has also been an obstacle for people in need of protection.[67] Limited access to interpreters and translators—available only following a request from lawyers—hinders access to information.[68]

Royal Decree 162/2014 provides for agreements to be concluded with Bar Associations in order to provide legal assistance to detainees (Article 15.4). In response to the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture’s (CPT) 2014 report, in which the committee recommended that measures be taken to ensure that detainees have access to lawyers, the Spanish government stated that “several collaboration agreements have been concluded with a number of Bar Associations.”[69] In 2014 however, NGOs noted that only one agreements had been reached (with the Bar Association of Barcelona) and that there was no budget allocated for the planned agreements.[70] In 2017, NGOs denounced attempts by the management in some CIEs to curtail their role and prohibit the legal socio-cultural activities NGOs had previously provided. However, this interpretation was overturned by the courts which confirmed the established framework for visits by NGOs.[71]

In 2009, reform of the Aliens Act created the figure of the supervisory judge (juez de control) (Article 62.6). This is the first instance criminal judge of the jurisdiction in which a detention centre is located and who is responsible for monitoring the application of the law and respect of detainees’ human rights (RD 162/2014, Article 2). Supervisory judges have played an important role in improving the living conditions in some facilities.[72] For example, in 2015 three judgments by supervisory judges in Barcelona, Madrid, and Las Palmas found that CIE managements had arbitrarily deprived detainees of legal rights and guarantees, including in relation to removal of private property, the use of mobile phones, time allocated for showers, access to health care, information prior to expulsion, and legal assistance.[73] However, improvements remain uneven among CIEs depending on the jurisdiction in which they are based. Furthermore, judges’ rulings are contingent upon the submission of complaints, which in turn depends upon the availability of legal assistance.

Some observers have argued that there is evidence of impunity related to the handling of complaints in detention centres. The NPM has contended that authorities have failed to investigate complaints of ill-treatment,[74] and according to one scholar, there has been little follow up to the hundreds of complaints lodged with the Ombudsman. Detainees who lodge complaints are often immediately expelled; access to witnesses is difficult; medical records are not available; and relevant security and police officials involved do not carry visible identification tags.[75]

2.10 Non-custodial measures (“alternatives to detention”). The Aliens Act does not specifically provide “alternatives to detention.” It does, however, provide a series of non-custodial or “precautionary” measures for people who may be subject to deportation. These include: withdrawal of passport or proof of nationality; reporting requirements; compulsory residence in a particular place; and any other injunction that the judge considers appropriate and sufficient (Article 235.6).

Circular 6/2014 also refers to other cautionary measures, according to Article 61.1 of the Aliens Law, including reporting obligations and withdrawal of passport or proof of nationality.

According to civil society groups, in practice these measures do not appear to be regularly contemplated for asylum seekers.[76]

2.11 Detaining authorities and institutions. Spain’s immigration detention centres are overseen by the Interior Ministry and are managed by the General Police Directorate (Dirección General de Policía). The country’s law permits the ministry to outsource services to other ministries or public and private entities (see 2.15: Privatisation).[77]

2.12 Regulation of detention conditions and regimes. In March 2014, the government approved its first set of regulations on operations at CIEs (Royal Decree 162/2014). These regulations include an organisational structure and the recognition of some detainee rights—such as the right to information, social services, health care, communications and visits, security and privacy, counsel and interpretation, and religious practice. However, the regulations have been criticised by NGOs and academics for failing to establish norms that would improve living conditions and guarantee full access to rights.[78] In particular, the regulations have been criticised for retaining a police-oriented model and for failing to provide sufficient guarantees for the protection of detainees’ rights. The Supreme Court has also criticised the Decree and declared four clauses unconstitutional. This context has generated complaints before both institutions of control: the Ombudsman and the first instance criminal judges who have played a key role in urging authorities to make changes in the management of CIEs. According to the Aliens Act, detention facilities should not resemble prisons and should only deprive detainees of their right to free movement (Articles 60.2 and 62).

2.13 Domestic monitoring. An active NGO network and the National Ombudsperson in its role of NPM regularly report on conditions in Spanish detention centres. The Prosecutor General and supervisory judges also visit the facilities. In February 2018 for example, the Ombudsman testified before a mixed parliamentary commission. Based on 44 monitoring visits to CIEs since 2010, he listed the many flaws in the operation of CIEs and in particular argued that they are not conceived to be “reception centres” for persons recently rescued from the sea.[79]

Although Spanish law guarantees civil society access to places of detention, NGOs have at times been denied access (Aliens Act, Article 62 bis; BO 2012a; APDHA 2012).[80] There are frequent criticisms of the fact that there is no clearly established regime or set of rules for NGO visits, and that the criteria for accessing facilities depends on each individual CIE director.[81]

In view of the Covid-19 crisis, Pueblos Unidos has created an online resource with information and publications concerning access to services during the state of emergency. The page also provides links to documents published by other organisations.[82]

2.14 International monitoring. As a state party to the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Spain receives monitoring visits from the CPT. Spain has also received detention-related recommendations from four UN human rights treaty monitoring bodies: the HRC[83], the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR),[84] the CAT[85], and the CRC.[86]

2.15 Trends and statistics. Between 2011 and 2015, the number of people placed in immigration detention fell by 50 percent: from 13,241 in 2011 to 11,325 in 2012, 9,020 in 2013, 7,286 in 2014, and 6,930 in 2015.[87] While detention rose again in 2017 to 8,814, in 2018 it dropped back to 7,855 (including 179 women) and to 6,473 in 2019.[88] That year, the main nationalities were Moroccan (36 percent of all detainees) and Algerian (32 percent).[89]

According to the National Police, the drop in detention numbers was due to the use of improved criteria to assess the need for detention and increased police cooperation with countries of origin and transit.[90] This led to a drop in mass identification controls, from 90,406 in 2011 to 30,306 in 2015.[91]

However, parallel to the decline in detention numbers has been an increase in summary expulsions (expulsiones exprés)—in which individuals are removed from Spanish territory directly from police stations within 72 hours of apprehension. This form of expedited removal bypasses the intervention of the juridical power, raising concerns about the protection needs of those deported.[92]

The lower level of detention might also be correlated to another set of figures. According to Eurostat data, 49 percent of non-EU citizens (230,540 persons) refused entry at EU-28 external borders by Member States in 2018 were recorded in Spain. By comparison, France—which ranked second in terms of most entry refusals—refused entry to 70,445 persons. [93]

Since 2015, the number of persons applying for international protection in Spain has more than tripled: from 14,780 applicants in 2015, to 15,755 in 2016, 36,605 in 2017, and 54,050 in 2018.[94] This number increased significantly in 2019, with 117,800 applications lodged during the year, out of which the large majority originated from Latin American countries, namely Venezuela (40,906), Colombia (29,363), Honduras (6,792), Nicaragua (5,931) and El Salvador (4,784).[95] Of those submitted in 2018, 1,386 were filed from immigration detention.[96] In 2018, more persons arrived by sea than the previous eight years combined—according to data provided by the Interior Minister, there were 57,498 sea arrivals.

The percentage of detainees who are deported has stood below 50 percent for several years: in 2018 45.8 percent of detainees were deported.[97] This low deportation rate from detention is due to the high number of inexpulsables (non-deportable persons) placed in detention, which observers have argued demonstrates that detention has become an arbitrary form of punishment that “criminalises migrants.”[98]

With the onset of the Covid-19 crisis in early 2020, it was immediately clear that deportations could no longer be carried out given the closure of borders and grounding of most international flights, resulting in many detainee’s detention orders losing their legal basis. As such, the Spanish Ombudsman and the Campana Estatal por el Cierre de los CIEs urged authorities to release detainees.[99] Subsequently, the Interior Ministry advised that detainees who cannot be deported or who have been detained for longer than the maximum period (60 days) should be released and by 6 May, Spanish authorities announced that its CIEs were completely empty.[100]

2.16 Privatisation. The management of immigration detention centres has not been placed in private hands, though some political forces (including the rightist party Ciudadanos) have proposed to privatise management and security inside detention centres in order to “modernise” them and to re-open closed wings in prisons for immigration detention.[101] Some services in detention centres are provided by the private sector, including medical services (Sermedes, Clínicas Madrid) and interpretation.[102] NGOs and academics have criticised this practice of outsourcing for its failure to establish norms that would improve living conditions and guarantee full access to rights.[103]

2.17 Cost of detention. In 2013, the NPM estimated that the annual cost of maintaining CIEs amounted to some 8.8 million EUR.[104] (In reports published since then, information on costs has not been included.) The costs of immigration detention are closely embedded in other related costs.[105] For instance in 2013, the Spanish companies EU LEN Seguridad and Serramar Vigilencia Seguridad signed a contract worth 6.5 million EUR with the Spanish state for the surveillance of CETIs in the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.[106]

2.18 Externalisation. Spain has long sought to extend its migration controls beyond both its land and maritime borders, leading to criticism that the country is violating the rights of migrants and asylum seekers.[107] This has included EU and Frontex assistance in interdicting boats en route to the Canary Islands, financing detention operations in Mauritania, and facilitating cooperation between police forces from Senegal to Morocco on migration control.[108] These efforts have coincided with the ebb and flow of migration patterns across the Mediterranean.

In 2006, in an effort to stem the flow of migrants to the Canary Islands, which had become important destinations as routes through North Africa were progressively blocked, the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation provided assistance to Mauritania to set up the country’s first dedicated detention centre for unauthorised migrants, sometimes referred to as “El Guantanamito.”[109] This spurred questions over who controls the facility. Officially, the Mauritanian National Security Service appeared to manage the facility, yet in 2008, officials stated that Mauritanian authorities performed their jobs at the express request of the Spanish government.[110]

The question of jurisdiction with respect to Spain’s activities in Mauritania were addressed in the UN CAT’s Marine I Case, which involved a different ad hoc detention facility—this one located in an abandoned fish-processing facility in Nouadhibou—used by Spain after it aided passengers aboard a smuggling boat that had lost power in international waters off the coast of West Africa in 2007.[111] While the UN CAT ultimately ruled that the case itself was inadmissible because the complainant, a Spanish citizen working for a human rights NGO, did not have standing, it nevertheless rejected claims by Spain that the incidents covered in the case occurred outside Spanish territory. Citing its General Comment No. 2, which provides that a state’s jurisdiction includes any territory where it exercises effective control, the Committee found that Spain: “[M]aintained control over the persons on board the Marine I from the time the vessel was rescued and throughout the identification and repatriation process that took place at Nouadhibou. In particular, the State party exercised, by virtue of a diplomatic agreement concluded with Mauritania, constant de facto control over the alleged victims during their detention in Nouadhibou. Consequently, the Committee considers that the alleged victims are subject to Spanish jurisdiction insofar as the complaint that forms the subject of the present communication is concerned.”[112]

Since then, and particularly in the wake of the 2015 refugee “crisis” in Europe, Spain’s externalisation efforts have continued to evolve. In 2019, reports revealed that security equipment, including helicopters and boats from Spain’s Guardia Civil, which were first put in place in Senegal in 2006 as part of the effort to block migration to the Canaries, continued to be used, with patrols jointly undertaken by both Spanish and Senegalese officers.[113]

Also in 2019, the Spanish government proposed a plan to reduce irregular immigration by 50 percent by ending active rescue patrols along the Mediterranean coast and prohibiting NGO rescue boats from docking.[114] Although the country’s Interior Ministry walked back this proposal, the government unveiled a strategy ahead of the 2019 EU election aimed at reducing arrivals, including by tasking the Guardia Civil with control of sea rescue and increasingly relying upon Morocco’s coastguard to intercept vessels.[115]

3. DETENTION INFRASTRUCTURE

3.1 Summary. As of May 2020, Spain operated seven immigration detention facilities, or “centres of internment for foreigners” (centros de internamiento (CIEs). In December 2018, it was reported that their total capacity was 1,589.[116] According to JRS Spain, while two facilities physically exist in the Province of Cadiz—one in Algeciras and another in Tarifa—they are legally considered to be one single facility.[117] In 2018, authorities announced plans to construct a new CIE in Botafuego-Algeciras, which would eventually replace the Algeciras and Tarifa facilities. While these plans have been approved, the facility had yet to be constructed at the time of this publication.[118]

People arriving in Spain by sea automatically receive detention orders and are detained in police stations for up to 72 hours while they await removal. Police stations in Malaga, Tarifa, Almeria, and Motrila are mainly used for these purposes.[119]

The country has used transit facilities (also known as sala de asilos) at key airports, including the Lanzarote Airport on the Canary Islands and Madrid’s Barajas Airport, for periods exceeding 24 hours.[120] However, the National Mechanism for the Prevention of Torture reported that in 2014 a significant number of people were detained at Barajas Airport for more than 72 hours, pending asylum requests.[121] Persons who apply for asylum at borders or in airports in transit ad hoc spaces (Salas de Inadmisión de Fronteras) are de facto deprived of liberty for up to four days, extendable to 10 days.[122]

In 2019, occupancy rates in CIEs were: 81.46 percent in Algeciras CIE; 64.24 percent (Barcelona CIE); 71.14 percent (Madrid-Aluche); 78.66 percent (Murcia); 70.93 percent (Valencia); 53.34 percent (Las Palmas), and 47.27 percent (Tenerife).[123] However, following the eruption of the Covid-19 crisis, which hit Spain acutely in March and April 2020, the country released large numbers of immigration detainees and temporarily closed certain CIEs (see: 2.14 Trends and Statistics). On 1 April, a judge ordered the release of all detainees in the Las Palmas CIE after several detainees contracted Covid-19, and as of 6 April, the Barcelona, Tenerife, Hoya Fria, Aluche, and Barranco Seco CIEs were temporarily closed, leaving 34 persons remaining in detention: 22 persons held in the Murcia CIE, 10 in the Valencia CIE, and two in Algeciras.[124] By 6 May, it was reported that all of Spain’s CIEs were empty.[125]

In 2018, faced with a surge in arrivals at the southern border (over 5,000 persons arrived each month between June and December, with a peak of 10,912 arriving in October), the government established several temporary reception centres (Centros de Acogida Temporal de Extranjeros - CATE) and Emergency Reception and Referral Centres (Centros de Acogida de Emergencia y Derivación - CAED).[126] However, the Spanish government has not adopted any legal instruments defining and regulating these two new types of centres.[127] Although Spanish NGOs acknowledge that the country faced a degree of urgency at its border in June 2018, they argue that local authorities had long been aware that available reception facilities were insufficient.

The country also makes use of “ad hoc”—surge or temporary—facilities, which are typically only used during the annual immigration swells in the Canary Islands and the North African enclaves of Melilla and Ceuta. These facilities—CETIs (Centros de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes)—are designed as places of first reception providing basic services to immigrants and asylum seekers who have entered Spanish territory illegally. Managed by the Ministry of Employment and Social Security, CETIs tend to function as semi-open centres with access restrictions in place at night.[128] However, in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, it was reported that CETIs had become closed facilities with those inside unable to leave except for urgent medical situations.[129]

3.2 List of detention facilities. Algeciras CIE, Barcelona CIE, Las Palmas (Gran Canara) CIE, Madrid CIE, Murcia CIE, Tenerife CIE, and Valencia CIE; transit zones at the Lanzarote and Madrid airports. Although people hosted in CETIs are usually free to leave,[130] authorities responded to Covid-19 crisis by converting them temporarily into closed facilities.[131]

3.3 Conditions and regimes in detention centres.

3.3a Overview. There have been long-standing concerns about conditions of detention in CIEs as well as inadequate provision of essential services. While some of these concerns have been addressed in recent years, others appear to remain outstanding.

Concerns regarding the country’s ad-hoc detention facilities in Spain’s north African enclaves, meanwhile, have also been regularly noted—included overcrowding, and material standards that fall below those of CIEs in mainland Spain.

3.3b CIEs. Following several incidents in CIEs, conditions in Spain’s network of detention facilities have received considerable scrutiny. In December 2019, for example, a detainee confined in the Valencia CIE secretly recorded videos highlighting the facility’s poor conditions, including dirty and broken toilets, dark cells filled with bunk beds, and black water leaking from showers.[132] Observers have regularly noted that facilities possess penal-like environments and lack adequate space, ventilation, water, heating, and toilets.[133] In response to such criticisms, authorities approved improvement plans for all CIEs in January 2019.[134]

While the Aliens Act and its Regulation states that all detainees in CIEs should have access to legal advice assisted by a translator, this is not always the case as has been reported by various institutions including the Spanish Attorney General’s Office in 2019,[135] Judge Diez Tejera in 2020,[136] and civil society organisations.[137] This remained the case in several CIEs even after judicial decisions requesting a solution. On 13 July 2018, the Trial Court n°8 in Las Palmas (juzgado de instrucción) insisted that the Ministry of Interior sign an agreement with the Bar Association of Las Palmas for the provision of legal advice. The Juzgado de Control de los CIE (oversight mechanism of CIEs) of Algeciras and Tarifa addressed the same issues in its decision of 21 March 2018, requiring the General Police Station of Aliens and Borders (Comisaría General de la Extranjería y Fronteras) to sign an agreement with the Algeciras section of the bar association of Cadiz to set up a legal aid service.[138]

Facilities lack a permanent medical presence—particular deficiencies have been noted during weekends and overnight—and detainees’ access to their own medical records is reported to be difficult. In 2014, JRS Spain reported that in Barcelona CIE, a doctor is only present in the facility between 08:00 and 15:00, while there is no doctor available at the weekend.[139] NGOs have urged centre administrations to properly implement pre-entry and pre-release medical screening.[140]

The need to adopt a protocol for communication of medical records between CETIs and CIEs, when people are transferred from one to the other, has also been urged.[141] NGOs have highlighted the difficulties many internees have had in accessing medical reports on injuries. These reports are of vital importance in cases of mistreatment. The Ombudsman has recommended handing reports on injuries to detainees and the supervisory judge.[142]

In most of the CIEs, the closing mechanisms of the cell doors have been reported as inadequate—in that they cannot open quickly in an emergency.[143] Some cells do not have toilets. In such cases, detainees must call the guards in order to access a toilet outside their cell should they need it during the night. In various instances, people have been forced to use bottles or the sink in their cells because guards refused to open the cells at night.[144] In its decision of 10 August 2018, the Juzgado de control del CIE of Valencia addressed the fact that there is limited space for visits—particularly given that NGOs and legal advice services must also use such spaces. It was thus requested that these spaces be expanded or that visiting hours be better adjusted.[145]

In July 2016, Carmen Velayos, General Secretary of a police trade union in Cadiz described the CIEs in Algeciras and Tarifa as old and obsolete buildings that are unhealthy for police staff and detainees alike.[146] The Tarifa and Algeciras facilities were also heavily criticised in terms of their infrastructure, living conditions, and safety following a visit to the facilities by a judge on 31 January 2018.[147] The same concerns were raised regarding the Murcia and Madrid CIEs.[148]

In 2015 the Supreme Court ruled against Article 55.2(1) of the Regulation of Organic law 4/2000 that allowed naked strip and body searches.[149] Lack of privacy continues to be an issue. There is no special room for those who are ill, so they are forced to share rooms with other detainees.[150] Communication between detainees and the medical staff is difficult because of the lack of interpreters, leading to situations in which other internees act as interpreters.[151] Regarding the visiting regime, frequent complaints include the time limit and the existence of physical separation between visitors and detainees.[152]

Convicted criminals awaiting deportation at CIEs are held in the same premises as other detainees who have not been criminally charged or convicted.[153] According to a police trade union, the mix of ex-convicts with administrative detainees is one of the largest problems in detention centres.[154] Academics have criticised this “administrativisation” of penal law whereby foreign prisoners are placed in facilities for administrative detention prior to criminal expulsion.

Key concerns of the Ombudsman in his latest report as the National Mechanism for the Prevention of Torture included shortcomings in sanitary and health care, in particular in terms of psychological and mental health, separation of convicted criminals from immigration detainees, provision of legal assistance, and training of police officials.[155]

From 2006 to December 2019, eight deaths within CIEs were reported.[156] In addition, accusations of torture in the CIEs have been constant in recent years. Several allegations of physical assaults by police officers in the CIEs of Barcelona[157], Valencia,[158] and Madrid[159] have been made throughout the years. In May 2019, 101 individuals detained at the Aluche CIE in Madrid wrote a letter to the surveillance judge, denouncing serious human rights violations.[160] Allegations of abusive treatment; continuous aggressions which remain unpunished; scarce medical assistance; lack of access to medicine; lack of psychological support; irregularities in expulsion procedures; obstacles and / or denial of access to the asylum procedure, and arbitrary access of family members or relatives for the purpose of visits were raised. NGOs such as SOS Racismo, Pueblos Unidos, and Plataforma CIEs No Madrid supported the complaint and in June 2019, more than 100 NGOs requested the resignation of the director of the Aluche CIE.[161]

In the Province of Cadiz, two detention facilities technically exist—one in Algeciras and one in Tarifa—however they are legally considered one entity. This was the case even before 2019, when they operated independently with their own direction and management. In official reports, the government has referred solely to Algeciras CIE (Tarifa is considered an annex).[162] In January 2019, the Council of Ministers approved a proposal to construct a new facility in Cadiz (Algeciras), which is reportedly intended to eventually replace the two existing facilities in the province.[163] Although the city council has made land available, construction has not yet started. Once completed, it will have capacity for 500 detainees.[164]

In response to criticisms of detention conditions by the Spanish Ombudsman, as well as NGOs, in 2019 authorities also approved plans to improve conditions inside all existing CIEs.[165]

3.3c CETIs. Designed as sites of first reception, which can provide basic services, CETIs accommodate migrants and asylum seekers in an irregular situation pending their transfer to mainland Spain. According to a report following a 2018 fact-finding mission conducted by Special Representative of the Secretary General on Migration and Refugees, persons tend to spend between two months and a year in these facilities.[166] Although people hosted in CETIs are usually free to leave,[167] authorities responded to the Covid-19 crisis by turning them into closed facilities, with only those requiring urgent medical attention permitted to leave.[168]

These ad-hoc facilities have repeatedly been criticised for their conditions. In 2015, the UN CAT asked Spain to ensure the physical and psychological integrity of all individuals in temporary holding facilities and encouraged the country to facilitate oversight activities by NGOs in the centres.[169] In 2018, the UN CESCR urged Spain “to ensure adequate conditions for migrants and asylum seekers in temporary migrant reception centres in Ceuta and Melilla.”[170] That same year, the Special Representative of the Secretary General on Migration and Refugees wrote that accommodation standards were “inadequate.” In particular, he noted that families were not accommodated separately, and that material conditions fell below the standards observed in mainland facilities.[171]

Particular concerns have also been raised regarding overcrowding, with observers regularly noting that facilities are operating beyond capacity. According to Amnesty International, Melilla CETI—which has capacity for 580 people—was confining 1,753 persons as of 2 April 2020.[172] This, coupled with the fact that authorities do not appear to have adopted protective measures in light of the Covid-19 crisis, has prompted various bodies to call for detainees to be urgently released from CETIs. On 17 April, the Spanish Ombudsman released a statement detailing his concern for the wellbeing of those held inside CETIs—particularly children—and urged authorities to transfer persons from such facilities to the Spanish mainland.[173] Amnesty International Spain similarly called for detainees to be transferred—particularly those with underlying health conditions.[174]

[1] Frontex, “Risk Analysis for 2019,” 2019, https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Risk_Analysis/Risk_Analysis_for_2019.pdf

[2] UNHCR, “Refugees & Migrants Arrivals to Europe in 2018 (Mediterranean),” 18 February 2019, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/68006

[3] UNHCR, “Refugee & Migrant Arrivals to Europe in 2019 (Mediterranean),” 18 March 2020, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/74670

[4] Eurostat, “Database,” 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

[5] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2019, p.7, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain

[6] R. Casey, “Aquarius Refugees and Migrants Disembark in Valencia Port,” Al Jazeera, 17 June 2018, https://bit.ly/2JWBw9Y

[7] L. Abellan, “El gobierno traza un plan para reducir un 50% la migración irregular,” El Pais, 30 January 2018, https://elpais.com/politica/2019/01/29/actualidad/1548793337_525330.html

[8] Z. Campbell, “As Spanish Rescue Policy Changes, Warnings Over Migrant Drownings,” The New Humanitarian, 27 June 2019, https://bit.ly/3cBvmaa

[9] S. Carrera, “The EU Border Management Strategy: Frontex and the Challenges of Irregular Immigration in the Canary Islands,” CEPS Working Paper 261, February 2007, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1338019

[10] Z. Campbell, “As Spanish Rescue Policy Changes, Warnings Over Migrant Drownings,” The New Humanitarian, 27 June 2019, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2019/06/27/spanish-rescue-policy-changes-warnings-over-migrant-drownings

[11] See, for example, Committee against Torture, J.H.A. v. Spain, 21 Nov. 2008, no. 323/2007

[12] European Court of Human Rights, “Case of N.D. and N.T. v. Spain,” 13 February 2020, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-201353%22]}

[13] S. Jones, “European Court Under Fire for Backing pain’s Express Deportations,” The Guardian, 13 February 2020, https://bit.ly/2zICG5C

[14] M. Hernández, “El motín en el CIE de Aluche, arma arrojadiza entre Podemos e Interior,” El Mundo, 19 October 2016, http://www.elmundo.es/madrid/2016/10/19/580758fce5fdea21278b45fd.html

[15] N. Herrero, “Investigan la muerte de un interno del CIE de València,” El Periódico, 16 July 2019, https://www.elperiodico.com/es/sociedad/20190716/investigan-muerte-interno-cie-valencia-7556338

[16] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2019, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain

[17] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Discriminación de origen – Informe CIE 2018,” 2019, https://sjme.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Informe-CIE-2018-SJM.pdf

[18] P. Sainz, “El Defensor del Pueblo confirma la liberación de internas de los CIE,” El Salto, 19 March 2020, https://www.elsaltodiario.com/coronavirus/defensoria-del-pueblo-confirma-la-liberacion-de-internas-del-cie

[19] M. Martin, “Los Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros se Vacían Por Primera Vez en Tres Décadas,” El País, 6 May 2020, https://elpais.com/espana/2020-05-06/se-vacian-los-centros-de-internamiento-de-extranjeros-por-primera-vez-en-tres-decadas.html

[20] These measures included the suspension of administrative deadlines during the pandemic and adapting the functioning of the National Reception System of International Protection. As a result, it was confirmed that residence permits would remain valid during the emergency, and that refugees and asylum seekers would not be required to possess valid documents in order to receive aid covering their basic needs (including asylum seekers who have not yet submitted asylum requests).

[21] B. Barakat, “مهاجرون تونسيون يستغيثون: فيروس كورونا يهددنا في مخيم مليلة” Al Araby Al Jadeed, 1 April 2020, https://bit.ly/3dXAruL

[22] Defensor del Pueblo, “El Defensor Plantea la Posiblidad de Que Ninos y Ninas Puedan Salir a la Calle de Manera Limitada y Tomando las Debidas Precauciones,” 17 April 2020, https://www.defensordelpueblo.es/noticias/defensor-crisis-covid/

[23] As amended and valid as of 4 September 2018 (Revisión vigente desde 04 de Septiembre de 2018), http://noticias.juridicas.com/base_datos/Admin/lo4-2000.html

[24] M. Martin, “Los Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros se Vacían Por Primera Vez en Tres Décadas,” El País, 6 May 2020, https://bit.ly/3604e2p

[25] J. Vargas, “El Espejismo de los CIE Vacíos: Reabrirán Cuando se Pueda Expulsar a Extranjeros,” Publico, 7 May 2020, https://bit.ly/3fSXxni

[26] Campaña por el Cierre de los Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros, “#LosCIEsNoSeAbren: Comunicado de la Campana Estatal por el Cierre de los CIE y el Fin de las Deportaciones,” 15 May 2020, https://ciesno.wordpress.com/

[27] P. Sainz, “El Defensor del Pueblo Confirma la Liberación de Internas de los CIE,” El Salto, 19 March 2020, https://www.elsaltodiario.com/coronavirus/defensoria-del-pueblo-confirma-la-liberacion-de-internas-del-cie

[28] Campaña por el Cierre de los Centros de Internamiento para Extranjeros, “Por el Cierre des los Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros y el Fin de las Deportaciones,” accessed on 2 April 2020, https://ciesno.wordpress.com/

[29] Europa Press, “Interior Abre la Puerta Liberar a Internos en CIE Tras Analizar ‘Caso por Caso’ Posibilidades de Retorno,” 19 March 2020, https://bit.ly/2WwloBr

[30] L. Marco, “La Policía Empieza a Liberar Internos del CIE de Valencia Ante la Imposibilidad de Deportarlos,” El Diario, 17 March 2020, https://www.eldiario.es/cv/Policia-CIE-Valencia-imposibilidad-deportarlos_0_1006849871.html

[31] El Diario, “Los Dos Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros de Canarias ya Están Vacíos,” 6 April 2020, https://bit.ly/2zFqLp7

[32] M. Martin, “Los Centros de Internamiento de Extranjeros se Vacían Por Primera Vez en Tres Décadas,” El País, 6 May 2020, https://elpais.com/espana/2020-05-06/se-vacian-los-centros-de-internamiento-de-extranjeros-por-primera-vez-en-tres-decadas.html

[33] M. Majkowska, “Countries are Suspending Immigration Detention due to Coronavirus. Let’s Keep it that Way,” Euronews, 29 April 2020, https://bit.ly/3bvWmqx

[34] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Vulnerables Vulnerabilizados – Informe Anual 2015,” 2016, http://www.sjme.org/sjme/item/815-2016-09-18-07-03-41

[35] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2019, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain

[36] Defensor del Pueblo, “El Defensor Insiste En La Necesidad De Mejorar La Primera Acogida De Personas Migrantes Que Llegan A Las Costas En Situación Irregular,” 2018, https://www.defensordelpueblo.es/noticias/dia-personas-migrantes/

[37] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Discriminación de origen – Informe CIE 2018,” 2019, https://sjme.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Informe-CIE-2018-SJM.pdf

[38] Professor José Miguel Sánchez Tomás (Criminal Law Professor), Email to Mariette Grange (Global Detention Project), 8 August 2016.

[39] M. Escamilla, “Mujeres en el CIE: Généro, Inmigración e Internamiento,” 2013, http://www.migrarconderechos.es/bibliografia/Mujeres_en_el_CIE

[40] Defensor del Pueblo, “El Asilo en España -La protección internacional y los recursos del sistema de acogida,” 2016, http://www.asylumineurope.org/sites/default/files/resources/asilo_en_espana_2016.pdf

[41] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European. Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2016, http://www.asylumineurope.org/sites/default/files/report-download/aida_es_0.pdf

[42] Defensor del Pueblo, “Interior Acepta La Recomendación Del Defensor Para Adecuar El Sistema De Registro De Las Solicitudes De Asilo En Los Cie A La Normativa Vigente,” 2018, https://www.defensordelpueblo.es/noticias/proteccion-internacional-cie-2/

[43] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “CIE y Expulsiones Exprés, Informe anual 2014,” 2014, http://www.sjme.org/sjme/item/794-cie-y-expulsiones-expres

[44] UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), “Concluding Observations on the Sixth Periodic Report of Spain, CCPR/C/ESP/CO/6,” 2015, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Countries/ENACARegion/Pages/ESIndex.aspx

[45] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European. Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2016, http://www.asylumineurope.org/sites/default/files/report-download/aida_es_0.pdf; Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Vulnerables Vulnerabilizados – Informe Anual 2015,” 2016, http://www.sjme.org/sjme/item/815-2016-09-18-07-03-41

[46] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2019, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain

[47] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Vulnerables Vulnerabilizados – Informe Anual 2015,” 2016, http://www.sjme.org/sjme/item/815-2016-09-18-07-03-41

[48] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Discriminación de origen – Informe CIE 2018,” 2019, https://sjme.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Informe-CIE-2018-SJM.pdf

[49] El Salto, “Un Menor Permanece Ingresado en el CIE de Valencia a Pesar de Probar que Tiene 16 Años,” 18 February 2020, https://www.elsaltodiario.com/cie/menor-ingresado-cie-valencia-zapadores-pese-probar-edad

[50] European Migration Network (EMN), “Annual Report on Immigration and Asylum Policies, National Report Spain (Part I),” 2014, https://bit.ly/2OxIHJ6

[51] Unidad de Extranjería de la Fiscalía General del Estado, “Memoria,” 2014.

[52] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2019, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain

[53] La Vanguardia, “‘Preocupación” en la Oficina de Derechos Humanos de la ONU por el trato que España da a los niños migrantes,” La Vanguardia, 17 February 2016, https://bit.ly/312nhoX

[54] UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), “Concluding Observations on the Combined Fifth and Sixth Periodic Reports of Spain, CRC/C/ESP/CO/5-6,” 2018, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRC/C/ESP/CO/5-6&Lang=En

[55] I. Quirante, and J. Autista, “La Purísima de Melilla: un centro con casi 700 niños y un amplio historial de denuncias,” Publico, 21 February 2019. https://bit.ly/2IDZjMC

[56] I. Domínguez, “Detenido un educador del centro de menores de Melilla acusado de apuñalar a uno de los chicos,” El Pais, 17 July. https://elpais.com/politica/2018/07/17/actualidad/1531837788_430886.html

[57] Defensor del Pueblo, “El Defensor Plantea la Posiblidad de Que Ninos y Ninas Puedan Salir a la Calle de Manera Limitada y Tomando las Debidas Precauciones,” 17 April 2020, https://www.defensordelpueblo.es/noticias/defensor-crisis-covid/

[58] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “CIE y Expulsiones Exprés, Informe anual 2014,” 2014, http://www.sjme.org/sjme/item/794-cie-y-expulsiones-expres

[59] U.S. Department of State, “Trafficking in Persons Report 2016,” 2016,. http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2016/

[60] C. Manzanedo, “Las calamitosas condiciones de internamiento en los CIE españoles,” In M.M. Escamilla (ed.), “Detención, internamiento y expulsión administrativa de personas extranjeras,” 2015, http://eprints.sim.ucm.es/34492/1/FINAL.%20DIC%202015%20LIBRO%20CGPJ.pdf

[61] UN Committee against Torture (CAT), “Concluding Observations on the Sixth Periodic Report of Spain, CAT/C/ESP/CO/6,” 2015, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Countries/ENACARegion/Pages/ESIndex.aspx

[62] I. Majcher, M. Flynn, and M. Grange, Immigration Detention in the European Union: In the Shadow of the “Crisis,” Springer 2020.

[63] Policia Nacional, “España recibió en 2015 menos del 1% de la inmigración irregular que llegó a la Unión Europea,” 2016, http://www.policia.es/prensa/20160721_2.html

[64] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Discriminación de origen – Informe CIE 2018,” 2019, https://sjme.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Informe-CIE-2018-SJM.pdf

[65] Interior Ministry, “Centro de internamiento de extranjeros,” 2019, https://bit.ly/2ri6BvW

[66] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “CIE y Expulsiones Exprés, Informe anual 2014,” 2014, http://www.sjme.org/sjme/item/794-cie-y-expulsiones-expres

[67] C. Manzanedo, “Las calamitosas condiciones de internamiento en los CIE españoles,” In M. M. Escamilla (ed.), “Detención, internamiento y expulsión administrativa de personas extranjeras.” 2015, http://eprints.sim.ucm.es/34492/1/FINAL.%20DIC%202015%20LIBRO%20CGPJ.pdf; Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Discriminación de origen – Informe CIE 2018,” 2019, https://sjme.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Informe-CIE-2018-SJM.pdf

[68] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European. Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2016, http://www.asylumineurope.org/sites/default/files/report-download/aida_es_0.pdf; Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Discriminación de origen – Informe CIE 2018,” 2019, https://sjme.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06Informe-CIE-2018-SJM.pdf

[69] European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT), “Response of the Spanish Government to the Report 2014,” 2015, http://www.cpt.coe.int/documents/esp/2015-20-inf-eng.pdf

[70] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “CIE y Expulsiones Exprés, Informe anual 2014,” 2014, http://www.sjme.org/sjme/item/794-cie-y-expulsiones-expres

[71] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Discriminación de origen – Informe CIE 2018,” 2019, https://sjme.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Informe-CIE-2018-SJM.pdf

[72] C. Manzanedo, “Las calamitosas condiciones de internamiento en los CIE españoles,” In M.M. Escamilla (ed.), “Detención, internamiento y expulsión administrativa de personas extranjeras,” C. 2015, http://eprints.sim.ucm.es/34492/1/FINAL.%20DIC%202015%20LIBRO%20CGPJ.pdf

[73] Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) Spain, “Vulnerables Vulnerabilizados – Informe Anual 2015,” 2016, http://www.sjme.org/sjme/item/815-2016-09-18-07-03-41

[74] Amnesty International (AI), “Hay alternativas: No a la Detención De Personas Inmigrantes: Comentarios al borrador del Gobierno sobre el reglamento de los centros de internamiento de extranjeros,” 2013, https://bit.ly/2K5xISQ

[75] L. Zorita, “Opacidad, indefensión e impunidad en los centros de internamiento de extranjeros,” Democracia y Justicia Internacional, Instituto de Derechos Humanos de la Universidad de Valencia, 2013.

[76] ACCEM, “Country Report: Spain,” Asylum Information Database (AIDA) and European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), 2019, https://www.asylumineurope.org/reports/country/spain