A. The removal operation: preparations and conduct; (Read full CPT report) 7. According to the data provided by the Immigration Office, published by the GeneralInspectorate of the Federal Police and Local Police (AIG)7 in its 2021 Annual Report on forced returnmonitoring, a total of 1 984 persons were subjected to a forced removal from Belgium, […]

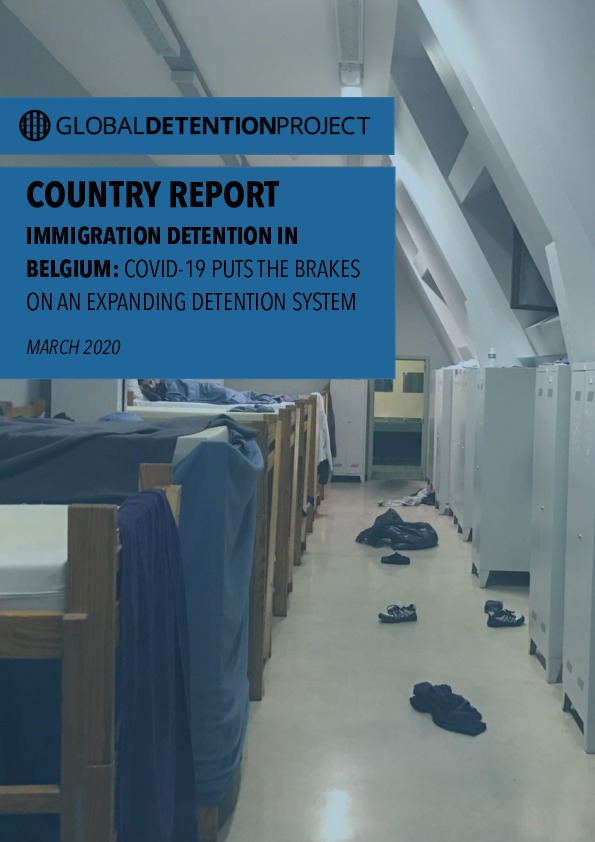

Belgium: Covid-19 and Detention

The Belgian NGO Vluchtelingenwerk Vlaanderen reported that during 19-22 October 2021, between 60-150 asylum seekers were being denied access to the asylum registration procedure per day, and in consequence did not have access to reception. As reported on 11 August 2020 on this platform, many asylum seekers were sleeping rough after being released from detention. […]

Belgium: Covid-19 and Detention

According to an international organisation official who asked to remain anonymous, but whose identity was verified by the GDP, while no moratorium on new immigration detention orders was established, fewer detention orders have been issued since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Director-General of the Immigration Office (IO) and the Minister for Asylum and […]

Belgium: Covid-19 and Detention

Global Detention Project Survey completed by Laura Cleton (@LauraCleton), University of Antwerp IS THERE A MORATORIUM ON NEW IMMIGRATION DETENTION ORDERS? There has been no public information on whether new detention orders are still being made. In terms of Orders to Leave the Territory (OLT), the Minister for Social Affairs, Public Health, Migration and Asylum, […]

Belgium: Covid-19 and Detention

Authorities announced that they had expanded access to the labour market for asylum applicants (if they have already submitted their application). Authorities hope that they can help make up for the lack of workforce – particularly seasonal workers – in the country. From 20 March 2020, the Brussels local government will be hosting 100 homeless […]

Belgium: Covid-19 and Detention

Belgium halved its immigration detention capacity (from 609 to 315 spaces) in the weeks after the outbreak of the pandemic. By 19 March, the total number of detainees in the country’s six detention centres had dropped to 304. However, because reception centres for asylum seekers are no longer accepting new arrivals and detainees are being […]

Last updated: March 2020

DETENTION STATISTICS

Average Daily Detainee Population (year)

Immigration Detainees as Percentage of Total Migrant population (Year)

DETAINEE DATA

DETENTION CAPACITY

ALTERNATIVES TO DETENTION

ADDITIONAL ENFORCEMENT DATA

PRISON DATA

POPULATION DATA

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DATA & POLLS

LEGAL & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

Does the Country Have Specific Laws that Provide for Migration-Related Detention?

Detention-Related Legislation

Do Migration Detainees Have Constitutional Guarantees?

Additional Legislation

Bilateral/Multilateral Readmission Agreements

GROUNDS FOR DETENTION

Immigration-Status-Related Grounds

Non-Immigration-Status-Related Grounds in Immigration Legislation

Criminal Penalties for Immigration-Related Violations

Grounds for Criminal Immigration-Related Incarceration / Maximum Length of Incarceration

LENGTH OF DETENTION

DETENTION INSTITUTIONS

PROCEDURAL STANDARDS & SAFEGUARDS

Procedural Standards

Types of Non-Custodial Measures (ATDs) Provided in Law

COSTS & OUTSOURCING

Description of Foreign Assistance

During the period 2014-2017, Belgium used funds provided through the EU's Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund (AMIF) for various detention-related activities, including one or more of the following: increased staff at detention facilities; renovation of detention facilities; operational costs of running detention facilities; interpretation and healthcare services; legal assistance for detainees; leisure, cultural and educational activities at detention facilities. Proposed future regulations for this fund include encouraging recipients to consider possible joint use of reception and detention facilities by more than one Member State (see "The Way Forward, p.39).

During the period 2014-2017, Belgium used funds provided through the EU's Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund (AMIF) for various detention-related activities, including one or more of the following: increased staff at detention facilities; renovation of detention facilities; operational costs of running detention facilities; interpretation and healthcare services; legal assistance for detainees; leisure, cultural and educational activities at detention facilities. Proposed future regulations for this fund include encouraging recipients to consider possible joint use of reception and detention facilities by more than one Member State (see "The Way Forward, p.39).

During the period 2014-2017, Belgium used funds provided through the EU's Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund (AMIF) for various detention-related activities, including one or more of the following: increased staff at detention facilities; renovation of detention facilities; operational costs of running detention facilities; interpretation and healthcare services; legal assistance for detainees; leisure, cultural and educational activities at detention facilities. Proposed future regulations for this fund include encouraging recipients to consider possible joint use of reception and detention facilities by more than one Member State (see "The Way Forward, p.39).

During the period 2014-2017, Belgium used funds provided through the EU's Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund (AMIF) for various detention-related activities, including one or more of the following: increased staff at detention facilities; renovation of detention facilities; operational costs of running detention facilities; interpretation and healthcare services; legal assistance for detainees; leisure, cultural and educational activities at detention facilities. Proposed future regulations for this fund include encouraging recipients to consider possible joint use of reception and detention facilities by more than one Member State (see "The Way Forward, p.39).

COVID-19 DATA

TRANSPARENCY

MONITORING

Types of Authorised Detention Monitoring Institutions

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MONITORING BODIES

National Human Rights Institution (NHRI)

NATIONAL PREVENTIVE MECHANISMS (OPTIONAL PROTOCOL TO UN CONVENTION AGAINST TORTURE)

NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS (NGOS)

GOVERNMENTAL MONITORING BODIES

INTERNATIONAL TREATIES & TREATY BODIES

International Treaties Ratified

Ratio of relevant international treaties ratified

Individual Complaints Procedures

Treaty Body Decisions on Individual Complaints

Relevant Recommendations or Observations Issued by Treaty Bodies

(a) The State party should refrain from placing applicants for international protection in detention at the border and should provide alternatives to detention, including by adopting the royal decree mentioned in the Aliens Act. The State party should use detention only in exceptional circumstances and as a last resort, on the basis of an individual assessment of each case and if other less coercive measures cannot be applied effectively;

27. The Committee recommends that the State party:

(a) Develop reliable indicators to determine the extent to which non-citizens are over-represented in prisons in order to be able to assess the situation and take the necessary measures to remedy any problem in this regard;

(b) Take the necessary measures to ensure in practice that irregularly staying migrants can have effective and non-discriminatory access to emergency medical assistance, education, health, housing and to lodge complaints without risk of arrest and forced removal;

c) Ensure that non-nationals of nationality outside the European Union can access the labor market and housing without discrimination on the basis of their nationality or origin;

d) Develop and implement specific strategies to mitigate the socio-economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on migrants, refugees, asylum seekers and stateless persons.

(Original in French)

27. Le Comité recommande à l’État partie de:

a) De développer des indicateurs fiables afin de déterminer dans quelle mesure les non-ressortissants sont surreprésentés dans le milieu carcérale afin de pouvoir évaluer la situation et prendre des mesures nécessaires pour remédier à tout problème à cet égard;

b) De prendre les mesures nécessaires pour garantir dans la pratique que les migrants en séjour irrégulier puissent avoir un accès effectif et sans discrimination à l’aide médicale d’urgence, à l’éducation, à la santé, au logement et à porter plainte sans risque d’arrestation et d’éloignement forcé;

c) Veiller à ce que les non-ressortissants de nationalité hors Union européenne puissent accéder au marché de travail et au logement sans discrimination du fait de leur nationalité ou origine ;

d) De développer et mettre en œuvre des stratégies spécifiques pour atténuer les effets socioéconomiques de la pandémie de COVID-19 sur les migrants, les réfugiés, les demandeurs d’asile et les apatrides.

§ 32: The State party should take all necessary measures to ensure that an individual assessment is carried out for each case of asylum, deportation or expulsion, with full respect for the principles of non-refoulement and safe third countries, in accordance with its obligations under the Covenant. The State party should also ensure the effective and independent monitoring of deportation operations.

§ 34: The State party should: (a) Continue its efforts to reduce overcrowding in prisons, including through the use of alternatives to detention, and improve living conditions at detention facilities, pursuant to the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules); (b) Provide for alternatives to the deprivation of liberty of persons with mental disorders at prisons; (c) Ensure implementation of Act No. 2019011569 of 23 March 2019 on the organization of the prison service and the status of prison staff, so as to ensure the minimum staffing levels at prisons, including during strikes.

(a) Develop a legislative framework on undocumented children;

(b) Establish status determination procedures to ensure the identification and protection of children in situations of migration, including unaccompanied children and separated children;

(c) Develop a standard protocol on age-determination methods that is multidisciplinary, scientifically based, respectful of children ’ s rights and used only in cases of serious doubt about the claimed age, consider documentary or other forms of evidence available and ensure access to effective appeal mechanisms;

(d) Integrate the principle of the best interests of the child in legislation and regulations concerning migration, ensure that this principle is given primary consideration in asylum and migration-related procedures, including age and status determination and deportation, and that children ’ s views are duly taken into account therein, and provide support to families with migration backgrounds to prevent family separation;

(e) Build the capacity of the authorities to determine and apply the best interests of the child in asylum and migration-related procedures;

(f) Ensure that all children in situations of migration, including undocumented and separated children, receive appropriate protection, are informed about their rights in a language they understand, have access to education and health care, including psychosocial support, and are provided with interpretation and free legal aid; and develop comprehensive referral, case management and guardianship frameworks for unaccompanied and separated children;

(g) Prohibit immigration detention of children and ensure non-custodial solutions, including foster care and accommodation in specialized open reception centres serviced by trained professionals and providing access to education and psychosocial support, ensure the periodic and independent review of the care and ensure access to complaint procedures...

42. With reference to the Committee ’ s general comment No. 6 (2005) on the treatment of unaccompanied and separated children outside their country of origin, the Committee recommends that the State party:

(a) Develop a uniform protocol on age-determination methods that is multidisciplinary, scientifically-based, respectful of children ’ s rights and used only in cases of serious doubt about the claimed age and in consideration of documentary or other forms of evidence available, and ensure access to effective appeal mechanisms;

(b) Effectively investigate cases of abuse with regard to unaccompanied children;

(c) Strengthen immediate protection measures for all unaccompanied children, and ensure systematic and timely referral to the guardianship service;

(d) Improve the provision of shelter to unaccompanied children, including by ensuring the availability of the youth welfare system and foster care for all unaccompanied children, regardless of their age."

§ 44. With reference to joint general comments No. 3 and No. 4 (2017) of the Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families/No. 22 and No. 23 (2017) of the Committee on the Rights of the Child on the human rights of children in the context of international migration, the Committee reiterates its previous recommendation (CRC/C/BEL/CO/3-4, para. 77) and urges the State party: (a) To put an end to the detention of children in closed centres, and to use non-custodial solutions; (b) To ensure that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration, including in matters relating to asylum and family reunification; (c) To develop and disseminate child-friendly tools to inform asylum-seeking children about their rights and the ways to seek justice.

> UN Special Procedures

> UN Universal Periodic Review

Relevant Recommendations or Observations from the UN Universal Periodic Review

REGIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MECHANISMS

Regional Legal Instruments

Relevant Recommendations or Observations of Regional Human Rights Mechanisms

necessary steps, including of a legislative nature, to review and strengthen the legal remedies against the removal order, to ensure no-one is sent back to a country where they run a real

risk of ill-treatment when removed. Further, the specific information on removal provided

upon arrival in a detention centre should include information on legal remedies against the

removal order, to ensure that they are made more accessible in practice.

23. the CPT would like to receive a confirmation that an assessment of the risk of ill-treatment had been carried out with respect to all eight persons removed to the DRC, based on their individual circumstances at the time of removal. Further, it would like to receive additional information concerning the functioning of the specialised legal unit and the role played by the EUR-LO in the assessment of the risk of ill-treatment.

25. The CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities ensure that a “last call procedure”

is put in place and effectively implemented in practice during all future removal operations

by air to guarantee that the escort leader and/or representative of the Immigration Office

onboard are always fully informed of the state of pending legal proceedings with suspensive

effect, up to the moment of handover.

26. The CPT would like to encourage the Belgian authorities to consider developing a system of

post-return monitoring and collecting relevant data and information on whether foreign

nationals removed by force to their countries of origin were exposed to treatment contrary to

Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights upon their return. It also encourages

the Belgian authorities to bring this matter to the attention of Frontex32 and the other EU

member states organising or participating in return operations supported by Frontex.

28. The CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities take the necessary measures, including of

a legislative nature, to ensure that all persons held in detention with a view to their removal

(irrespective of the number of previous removal attempts) are notified of their scheduled

removal at least several days in advance, to allow them to collect their personal belongings,

including documents and money, and be able to make the necessary arrangements to

prepare for their return.

31.The CPT encourages the Belgian authorities to provide information more systematically to

all persons subjected to forced removal on possible assistance and support upon their

return.

33. The CPT would like to receive the comments of the Belgian authorities. It would also

like to encourage the Belgian authorities to bring the issue of timely provision of information

about persons with vulnerabilities and/or disabilities being removed to the attention of

Frontex and the other EU member states organising or participating in return operations

supported by Frontex.

35.The CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities actively facilitate the right of returnees to

inform a relative, or third person of their choice, of their removal, including by granting

access to their mobile phones, if required.

40. In light of the previous paragraph, the CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities take

the necessary measures to ensure that:

All returnees are physically examined by the doctor of the detention centre on the day

when the “fit-to-fly” certificate is issued (that is a maximum of 72 hours prior to the

departure of the removal flight);

The cover sheet intended for transmission to the relevant administrative and police

authorities be revised accordingly and also no longer contains any information that is

covered by medical confidentiality;

The common standardised form “Medical report and information for return

operations”, which contains information that is covered by medical confidentiality, is

only transmitted to the healthcare staff accompanying the removal flight;

Both parts of the “fit-to-fly” certificate (namely the cover sheet and the common

standardised form) are systematically issued and thoroughly completed by the

doctors of the detention centres in which the returnees are detained.

42. The CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities take the necessary steps to ensure

that medical examinations prior to removal are conducted in a dedicated examination room

or space, and out of the hearing and – unless the healthcare professional concerned

expressly requests otherwise in a particular case – out of the sight of police officers and

custodial staff.

47.The CPT recommends that all escort officers of the Federal Police wear a visible identification

tag on their safety vests to ensure that they can be individually identified

(either by their name or an identification number

50.The CPT recommends that these precepts are effectively implemented in practice when

strip-searches are performed by the Federal Police in the context of removal operations.

60. The CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities take the necessary steps to improve

coordination with other member states participating in removal operations by air to ensure

that medical information on the returnees is complete and transmitted in a confidential

manner to the accompanying medical doctor in advance (see also the recommendation made

in paragraph 61). It would also like to encourage the Belgian authorities to bring this matter

to the attention of Frontex and the other EU member states organising or participating in

return operations supported by Frontex.

Further, the CPT would like to receive the comments of the Belgian authorities on the above,

and particularly on how they ensure the proper transmission of medical information to the

accompanying doctor.

61. The CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities take the necessary steps to ensure that

medical confidentiality is always strictly respected during return operations organised and

carried out by Belgium. It would also like to encourage the Belgian authorities to bring this

matter to the attention of Frontex and the other EU member states organising or participating

in return operations supported by Frontex.

74. The CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities ensure that all persons removed in

the context of removal operations supported by Frontex are provided with information on the

Frontex complaint mechanisms, both orally and in writing, in a language they can

understand. To this end, information leaflets and/or a poster should be made available to all

returnees prior to or during the removal operation to ensure that the complaints mechanism

is rendered accessible and effective in practice. The Committee would also like to encourage

the Belgian authorities to bring this matter to the attention of Frontex and the other EU

member states organising or participating in return operations supported by Frontex.

76.The CPT recommends that the Belgian authorities ensure that the AIG is provided

with the necessary resources to effectively carry out its mandate as the

national forced return monitoring system. In the long term, the Belgian authorities

should set up a national forced return monitoring system that is truly independent

(namely that is not operating under the authority of the FPS Home Affairs).

79.The CPT wishes to receive data on the number of detention orders that have been renewed

beyond five months in 2021 and 2022. Further, it would like to be informed of the safeguards

in place to avoid situations of prolonged detention due to frequently renewed detention

orders in practice.

HEALTH CARE PROVISION

COVID-19

Country Updates

Government Agencies

Ministry of the Interior - https://ibz.be/fr

Office des Étrangers I SPF Intérieur - https://dofi.ibz.be/en

International Organisations

UNCHR Office - https://www.unhcr.org/where-we-work/countries/belgium

IOM Office - https://belgium.iom.int/

NGO & Research Institutions

Federal Ombudsman office - https://www.federaalombudsman.be/nl

Belgian Leaguel of Human Rights - https://www.liberties.eu/en/about/our-network/belgian-league-of-human-rights

Amnesty International - https://www.amnesty.org/

Human Rights Watch - https://www.hrw.org/europe/central-asia/belgium