This week, on 19 and 20 October, the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC) will consider the fifth periodic report of the Republic of Korea. Amongst various concerns, numerous NGOs–including the GDP’s partner, the Association for Public Interest Law–have called on the committee to examine the country’s immigration detention practices and policies. Concerns include the detention […]

Republic of Korea: Indefinite Detention Without Due Process Guarantees Ruled Unconstitutional

In an important ruling, the Republic of Korea’s Constitutional Court has found that the country’s policy of indefinitely detaining migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers without due process guarantees is unconstitutional. […]

Republic of Korea (South Korea): Covid-19 and Detention

As of the end of 2019, there were an estimated 360,000 undocumented foreign nationals living in South Korea. Amidst fears that they would not seek testing and treatment for fear of being arrested, in late January South Korean authorities announced that they were scrapping the requirement for medical staff to report undocumented migrant patients to […]

Republic of Korea (South Korea): Covid-19 and Detention

The Republic of Korea took aggressive action early on in the Covid-19 outbreak to limit the progress of the coronavirus, including adopting strict border control and immigration detention measures. On 1 April, the government adopted a rule that requires all overseas arrivals—including South Koreans—to quarantine at home or at government-designated facilities for two weeks. Reports […]

Last updated: February 2020

South Korea Immigration Detention Profile

- Key Findings

- Introduction

- Laws, Policies, Practices

- Detention Infrastructure

- Download 2020 Profile

KEY FINDINGS

- There is no maximum time limit for the detention of non-citizens, including asylum seekers.

- The government does not provide adequate information or data about immigration detention, making it challenging to assess trends in the country or the overall scale of its detention system.

- Children, victims of trafficking, and other vulnerable groups can be subject to indefinite immigration detention.

- Although there have been attempts to improve conditions in detention centres, observers have described these facilities as “prison-like” and frequently decry the abusive treatment of detainees.

- The National Human Rights Commission has repeatedly called for improvements to immigration detention centres.

- The country applies a separate legal regime for North Koreans, who may be subject to “provisional protective measures”—including detention—for up to four months.

- The government leases transit zone detention facilities at international airports, which are operated by private companies to confine people who are denied entry or awaiting removal.

1. INTRODUCTION

Immigration policy in South Korea (the Republic of Korea) is characterised by tensions between the need for unskilled migrant workers and the objective of controlling the influx of unauthorised immigrants and asylum seekers. The government began stepping up efforts to curb undocumented migration in the early 1990s, but lack of consensus between different actors resulted in the restrained implementation of certain policies. In the early 2000s, however, the government started to systematically arrest, detain, and deport irregular migrants. According to observers in South Korea, this crackdown has recently grown in scale and intensity.[1]

In 2009, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK) concluded that immigration arrest and detention procedures frequently violated provisions in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the UN Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment.[2] A more recent investigation by the NHRCK, in 2017-2018, led to renewed calls for improving respect for the human rights of immigration detainees. The commission recommended easing the carceral trappings of detention centres, taking steps to limit the use of solitary confinement, providing detainees with access to the internet, improving training of staff, and increasing exercise time, among other measures.[3]

In October 2019, the South Korean Immigration Service announced that it would begin reinforcing measures aimed at preventing unauthorised employment “where encroachment on the domestic job market as well as impediment to the Korean culture are concerned.”[4] The notice stated that undocumented migrants must leave the country within six months or face deportation as well as having their information shared with the government of their country of origin. Those who do not comply would also be subject to re-entry bans for a maximum of 10 years.[5] People caught working in the construction industry illegally can be subject to the “One Strike Out” policy, which results in immediate deportation.

Also in 2019, the government adopted a policy called “Preliminary Declaration of Voluntary Departure,” which requires undocumented migrants to declare their intention to depart 15 days prior to their departure date. Previously, undocumented people who wanted to leave the country did not have to make a prior declaration before they departed.[6]

To justify increasingly hard-line immigration policies, Korean authorities point to growing migration and asylum pressures. By the end of 2018, according to official statistics, the number of foreigners living in South Korea had risen to 2.7 million.[7] The largest population was from China (1.1 million, or 45 percent), followed by Thailand (8.4 percent), Vietnam (8.3 percent), the United States (6.4 percent), Uzbekistan (2.9 percent), and Japan (2.6 percent).[8]

The number of asylum applications in 2018 nearly doubled from the year before, increasing to more than 16,000.[9] This was reportedly the highest number ever recorded. Of these, 2,496 (15 percent) were from Kazakhstan, 1,916 (12 percent) were from Russia, and 1,236 (eight percent) were from Malaysia.[10]

The increase in asylum seekers appears to have spurred some particularly harsh measures. For instance, in May 2018, after some 500 Yemeni nationals sought asylum on Jeju Island, a self-governing Korean province with an independent visa policy,[11] the government banned the refugees from entering the mainland pending the results of their refugee status determination procedure.[12] The move was widely criticised by civil society organisations for stoking racist, anti-refugee sentiment.[13] As of early 2019, only two of the applicants had been granted refugee status while another 56 had been ordered to leave Korea and some 400 had been granted temporary “humanitarian stay” permits.[14]

Despite the clear trend in hardening immigration and asylum policies, it is difficult to accurately account for detention and removal practices because of the government’s failure to publicly release information and statistics. One source in Korea from the organisation Advocates for Public Interest Law (APIL) told the Global Detention Project (GDP) that although the Ministry of Justice releases detailed statistics concerning the number of foreigners who have been imprisoned for criminal offenses, it does not include in its annual report data about people placed in immigration detention. In responding to freedom of information requests, officials have only provided partial data, such as statistics for individual detention centres (see: 2.14 Transparency and access to information). [15]

The bit of information that has been publicly released appears to show a downward trend in certain forms of immigration detention. In particular, the number of people in long-term detention (more than six months) decreased from 44 in 2017 to 20 in 2018.[16] A lawyer for APIL told the GDP that this decrease “is not based on foreigners' human rights or systematic remedies, but is arbitrarily done by the immigration office.” He added that currently the Ministry of Justice “is taking an attitude of prompt deportation or using temporary release at its own discretion more frequently to reduce the number of long-term immigration detainees.”[17]

2. LAWS, POLICIES, PRACTICES

2.1 Key norms. Article 12 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea provides that no person may be detained unlawfully. Any person who is detained has the right to legal counsel; and no one can be detained without being informed of the reason and of their right to legal counsel. In addition, any person who is detained has the right to request the court to review the legality of their arrest or detention. The Constitution stipulates that the territory of the Republic of Korea consists of the entire Korean peninsula and its adjacent islands; thus, those who “defect” from North Korea into South Korea are recognised as South Korean nationals.

The 1963 Immigration Control Act regulates the entry and exit of all nationals and foreigners to and from the Republic of Korea and the sojourn of foreigners staying in the Republic of Korea, among other functions, and is accompanied by an Enforcement Decree. This act also provides for the detention of non-citizens (Immigration Control Act, Article 2). The Korean Bar Association (KBA) notes that Korea refers to “detention” as “보호,” which corresponds to the word “protection” in English. However, given that Article 2 actually allows the immigration control official to “take into custody or impound” a person who may be subject to deportation, it clearly denotes a form of detention.[18]

In 2012, the South Korean parliament passed the Refugee Act, making South Korea the first country in Asia to enact an independent law for refugee protection.[19] The Refugee Act includes provisions giving refugee applicants access to determination procedures at entry ports and social security for refugees at the same level as Korean nationals. The act also allows for immigration detention for the purpose of verifying an applicant’s identity. It also allows the relevant immigration office or branch chief to order an applicant to “stay at a designated location” within the port of entry, pending a decision on whether they should be referred to the formal refugee status determination procedure (Article 6). The Refugee Act is also accompanied by an Enforcement Decree.

The 2018 Regulations on the Protection of Foreigners regulate conditions of detention. Additionally, specific provisions concerning North Koreans are provided in the 1997 Protection of Defecting North Korean Residents and Support of Their Settlement Act as well as the Act’s accompanying Enforcement Decree.

2.2 Grounds for detention. Grounds for immigration-related detention are provided in various laws, including the Immigration Control Act, the Refugee Act, and the Enforcement Decree of the North Korean Refugees Protection and Settlement Support Act.

2.2a Immigration detention. The Immigration Control Act provides for two different forms of immigration detention: internment and detention for deportation (Article 51). Internment covers the period during which a person is investigated for suspected violations of the Immigration Control Act, whereas detention for deportation occurs after the investigation has been completed and the detainee formerly enters deportation proceedings.

According to Article 51 of the Immigration Control Act, an “internment order” can be issued if there are “considerable reasons to suspect that a foreigner falls under Article 46(1), and he/she flees or might flee.” Article 46(1) defines the category of “persons to be deported,” as those who violate conditions of entry, stay, or exit. To apply for an internment order, the immigration control officer must submit an application detailing the reasons why internment is necessary (Article 51(2)). When there is insufficient time to obtain an internment order, an immigration control official may issue an “emergency internment note” (Article 51(3)). An internment order must then be obtained within 48 hours (Article 51(4)); otherwise the detained person is to be released. Article 56 provides for the “temporary internment” of any non-citizen whose entry violates provisions on entry inspection under Article 12(4), who have obtained a conditional entry permission under Article 13(1) and who have fled or appear very likely to flee; or who have obtained a departure order and who have fled or appear very likely to flee.

Immigration control officials or judicial police officials are in charge of executing deportation orders (Article 62). While executing a deportation order, the immigration control official must present the individual subject to deportation with the deportation order, and they should subsequently be “repatriated without delay” to their country of citizenship, or country from which they came to South Korea (Article 62). If the person subject to a deportation order is aboard a vessel, the immigration control official may hand over such a person to the captain of the vessel, or the forwarder, who has the obligation to repatriate the foreigner at their own expense and responsibility (Article 63). If immediate repatriation is not possible, a person can be detained until the deportation can be carried out (Article 63). If repatriation is clearly found to be impossible, the person can be released with “necessary conditions attached,” including restriction on residence (Article 63(4)).

2.2b Asylum detention. The Refugee Act provides two grounds for detention. Under Article 20, immigration officers may detain an asylum seeker for 10 days for the purpose of verifying their identity, with an Order of Detention issued according to Article 51 of the Immigration Control Act. The Refugee Act also provides for detention at the port of entry. Article 6(2) states that an asylum applicant awaiting the results of their application may be required to “stay at a designated location within the port of entry for a period not exceeding seven days,” while they await a decision on whether they will be referred to refugee status determination procedures. If an individual’s refugee status application or refugee status determination is rejected, they will be subject to deportation proceedings under the Immigration Control Act, including detention prior to deportation.

2.2c “Provisional measures” for North Koreans. Article 7 of the North Korean Refugees Protection and Settlement Support Act requires “[a]ny person escaping from North Korea” intending to apply for protection under the Act to do so in person with the head of an overseas diplomatic or consular mission, or the head of any administrative agency. Article 7 of the Act allows the director of the National Intelligence Service to “take provisional protective measures, such as investigations necessary for the decision on protection for a person applying for protection … and temporary personal protection measures” and to report their findings to the Minister of Unification, who makes the ultimate decision on eligibility for protection. These provisional measures can include detention at designated centres. The director determines the specific details of these measures, including operations at detention sites. In 2015, the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC) noted that people may be held in designated centres for up to six months, some without access to legal counsel; moreover, “defectors” may be deported to third countries without independent review.[20]

Arguably, this type of detention is not strictly “immigration-related” because people from North Korea are recognised as nationals of South Korea under the Korean Constitution, as discussed above (see: 2.1 Key norms).

2.3 Criminalisation. The Immigration Control Act provides numerous grounds for the prosecution of individuals for immigration-related violations, related to entry, stay, and exit (Article 93-3, Article 94, and Article 95). For example, Article 93-3 states that those who enter the Republic of Korea without undergoing an entry inspection in violation of Article 12 should be punished by imprisonment with labour for a maximum of five years or by a fine not exceeding 30 million KRW (approximately 25,220 USD).

Article 94 provides that individuals who commit the following offences will be punished by imprisonment with labour for a maximum of three years or a fine not exceeding 20 million KRW (approximately 17,260 USD) if they: violate conditions on entry, including holding a valid passport and visa, or other permission for entry (Article 7); engage in activities permitted under a different status of stay without obtaining permission to engage in those activities (Article 20); violate the restriction set by the Minister of Justice on their scope of residence or activities which are deemed necessary for the public peace and order or national interests of Korea (Article 22); or who depart from Korea without undergoing departure inspection (Article 28).

Article 95 provides that individuals who flee while being detained or temporarily detained, or while being escorted for detention or deportation (Article 51), or who violate the restrictions on their release from detention (Article 63), may be punished with imprisonment with labour for a maximum of one year, or a maximum fine of 10 million KRW (approximately 8,630 USD).

Non-citizens who are arrested, but whose sentences have yet to be confirmed, are detained in various prisons that are not exclusively used for non-citizens. Those who are subsequently sentenced to imprisonment, meanwhile, are confined in one of three specific prisons: Cheonan Prison, Daejeon Prison, and Cheongju Women’s Prison.[21] In certain cases, when the criminal offence is deemed grave enough, non-citizens can lose their residence status or have their visa revoked. In these cases, the non-citizen is transferred to immigration custody after completing their criminal sentence and confined in an immigration detention facility until they are deported.[22]

Although detailed statistics revealing the extent to which non-citizens are imprisoned for violating entry regulations are not available, observers note that imprisonment is rarely ordered. Instead, persons found to be violating these provisions are more typically subjected to detention and deportation procedures.[23]

2.4 Asylum seekers. North Korean law differentiates between non-Korean asylum seekers and “defectors” from North Korea seeking protection.

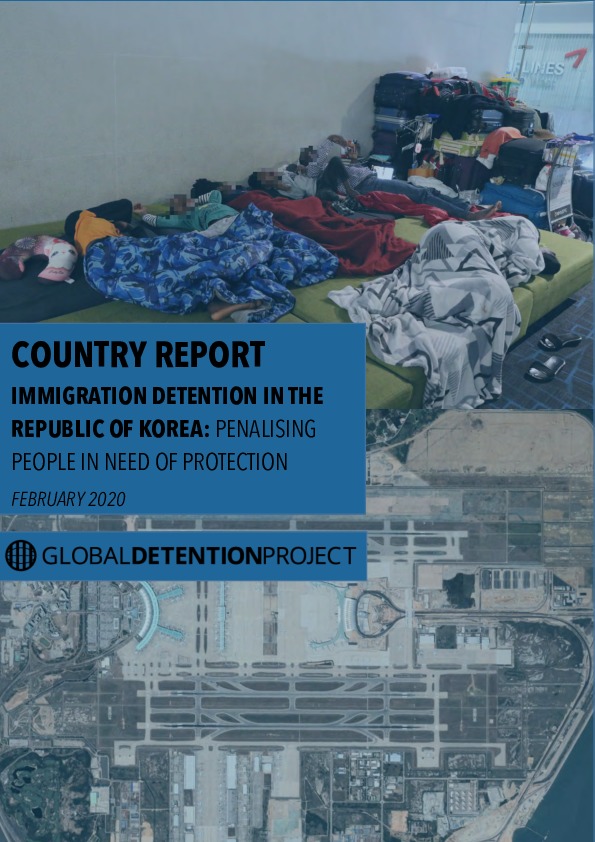

2.4a Non-Korean asylum seekers. According to Article 6 of the Refugee Act, any person who wishes to apply for refugee status at a port of entry such as an airport must first submit a written Application for Recognition of Refugee Status. The Minister of Justice must decide within seven days whether to refer the application to the formal refugee status determination (RSD) procedure. During those seven days, the applicant may be required to stay at a designated location within the port of entry; they must also be provided with basic food, accommodation, and clothing. This location is called a Refugee Status Waiting Room. In practice, however, most asylum seekers are made to wait in the Deportation Waiting Room, alongside persons who have been issued deportation orders.[24]

NGOs have criticised the Korean immigration authority for denying people the possibility of referral to a formal RSD procedure through this preliminary screening procedure. In 2017, the rate of referral of applicants to formal RSD procedures at the port of entry was just 10 percent.[25] The rate increased to 46.7 percent in 2018.[26] In one case, a Sudanese asylum seeker fleeing forced conscription was denied referral to RSD on the basis that his purpose of entry—to seek asylum—did not comply with his visa, which was for a short business trip. He was also accused of avoiding his military responsibilities, which meant that his claim was “manifestly ill-founded.”[27]

The recognition rate for refugee status is very low. At the level of the Ministry of Justice, the average rate of refugee recognition of the first instance decision remained at 0.66 percent from 2013 to 2018.[28] The refugee acceptance rate was three percent as of May 2018.[29] The NHRCK has previously said that the Ministry of Justice lacks the capacity to handle refugee cases. For example, in 2016, the Seoul Immigration Office received 6,224 of 7,542 applications for refugee status. With only 22 staff members in the Immigration Office, this meant that every officer had to handle around 280 refugee applications each to cover the load. NGOs have also criticised the lack of adequate interpretation services.[30] According to one NGO report, as of 2018, there were 174 trained interpreters for refugees, with just 10 available Arabic interpreters.[31]

Although an appeal procedure for rejected refugee applications does exist, many organisations have criticised the Refugee Committee, which is responsible for deliberating on applications, for its lack of independence, expertise, and transparency. The NHRCK stated that the committee “conducts its deliberation based only on papers without having hearing procedures, and … deals with a large number of cases at once in each session.”[32]

There is no appeal procedure for non-referral to RSD procedures. The applicants who are not referred to RSD procedures at the border are sent to a Deportation Waiting Room, pending their repatriation. APIL argues that the unbearable conditions in the Deportation Waiting Rooms may lead some applicants to leave Korea, which may constitute de facto refoulement.[33] The high rate of non-referral to RSD procedures and the lack of a clear legal definition of what constitutes a “manifestly-unfounded claim” also raises the possibility that Korea’s laws and practices may be in breach of the principle of non-refoulement.[34]

2.4b North Korean “defectors.” The 1997 Protection of Defecting North Korean Residents and Support of Their Settlement Act provides specific protection and support to “North Korean residents defecting from the area of the Military Demarcation Line and desiring protection from the republic of Korea” (Protection of Defecting North Korean Residents and Support of Their Settlement Act, Article 1). Article 4 of the Act provides that “South Korea shall provide protected persons with special care on the basis of humanitarianism.” Those who have “defected” must make an application to the head of a South Korean overseas diplomatic or consular mission stating that they wish to be protected under this Act. Subsequently, the Minister of National Unification will decide on the admissibility of their application. If the person is “likely to affect national security to a considerable extent,” it is the responsibility of the director of the Agency for National Security Planning to decide on the admissibility of the application, and inform the Minister of National Unification (Protection of Defecting North Korean Residents and Support of Their Settlement Act, Article 8). Additionally, Article 10 of the Enactment Decree of the North Korean Refugees Protection and Settlement Support Act states that a resident of North Korea may not apply for protection in South Korea if they have a mental disorder; a member of their family applies for protection by proxy of the rest of the family members; or “where there exist other urgent grounds.”

When North Korean residents arrive in South Korea, they are held in the North Korean Detention Protection Centre. According to the NHRCK and NGO reports, North Korean defectors have limited freedom of movement and often lack access to legal counsel in the centre.[35][36] If the Minister of National Unification or the Director of the Agency for National Security Planning determines that a person is not eligible for protection under the North Korean Refugees Protection and Settlement Support Act, they may be deported to a third country, without the possibility of an independent review on the decision.[37] In 2015, the HRC recommended that the government “adopt clear and transparent procedures that provide for review with suspensive effect by adequate independent mechanisms before individuals are deported to third countries.”[38]

2.5 Children. According to the Korean government, in principle children seeking asylum are not placed in immigration detention. However, children can be detained alongside their parents when their parents so request, or if no guardian is available to care for the child while their parents are detained.[39] In such circumstances, children are placed in special rooms and an officer is designated to take care of them.[40] In 2019, the government also reported that migrant children under the age of 14 may be placed in detention only when deemed “unavoidable to ensure the safety of such children.”[41]

The Immigration Control Act does not contain specific provisions regarding the detention of migrant children—although Article 56-3 does provide that people under the age of 18 who are detained should be given special attention by staff in detention centres. Article 4(2) of the Rules on the Protection of Foreigners states that the head of a detention centre may grant permission to a detained non-citizen to bring a child under the age of 14 who is not subject to detention into the facility, if the non-citizen is the sole supporter of the child. A non-citizen may also bring a child under the age of three into the facility, even if another person wants to support the child, if they are the child’s parent. In cases where children enter the detention facility to join their parents, there should be minimal restrictions on their actions and movements (Rules on the Protection of Foreigners, Article 4(3)). The Rules on the Protection of Foreigners also include provisions on education and protection of children in detention centres. Article 4(4) states that the head of the immigration detention facility may, in accordance with the age of the child, provide educational services or delegate educational support to charitable organisations. Article 9(5) stipulates that, if necessary, the head of the centre may provide a separate family room for children and parents to live together.

Non-citizens usually have no alternative way of ensuring that their child is protected and well cared-for; as such, they will usually give consent for their children to be detained with them. This has led NGOs to argue that detention of migrant children is “practically compulsory.”[42] In 2015, a coalition of NGOs recommended that the government institute an “exception free principle of non-detainment of children.”[43]

The NHRCK reported that between 2015 and 2017, a total of 225 children were detained, including a two-year old girl who was detained for 50 days.[44] In 2018, the NHRCK stated in its review of the upcoming revision to the Immigration Control Act that detention should never be applied to a child unless detention is in the best interests of the child.[45]

The Korean Immigration Office has also previously prevented non-citizens and their undocumented children from leaving the country, if the non-citizens have outstanding fines resulting from their failure to register their children as foreigners. In 2017, two families with undocumented children attempted to voluntarily leave the country, but were prevented by airport immigration officers at Gimpo and Incheon Airport. Immigration officers at both airports ordered each family to pay administrative fines of 2.2 million KRW (approximately 1,900 USD) and 850,000 KRW (approximately 733 USD) respectively, and notified them that they would not be able to leave the country until the fines were paid.[46] NGOs have criticised the Korean government for restricting migrant children’s freedom to exit the country on the basis of their undocumented status.[47]

2.6 Other vulnerable groups. There are no legal guarantees in Korean legislation limiting the placement of vulnerable persons in immigration detention. However, Article 56-3(3) of the Immigration Control Act lists four categories of people who should be given special protection in detention: sick people; pregnant women; the elderly; and those under 18 years of age. Article 56-4(1) states that additional personnel may be deployed to protect, or a separate room may be allocated for the protection of people with the following characteristics: suicidal or self-harming tendencies; those who may commit harm or harm other people; those who flee or who may want to flee; or those who unreasonably refuse or avoid the authority of the immigration service official, or who harass the official. Article 4(4) of the Regulations on the Protection of Foreigners states that the heads of detention facilities must designate an official to monitor those foreigners needing special protection, and conduct interviews with them every two weeks in order to identify and provide assistance for any needs that arise (Article 4(5) and 4(6)).

Victims of trafficking reportedly receive limited protection in South Korea, many of whom are lured into the country on “entertainment” visas. According to a 2007 NGO report, “[T]he government…created a provision in the Immigration Control Act that penalizes agents and employers who confiscate passports or certificates of inscription as a means of securing foreign females’ financial obligations under the contract and payment of debt. However, under the same Immigration Control Act, if a migrant woman in the sex industry flees from the employer’s unjust demands and human rights infringement, the employer will simply report that the migrant worker abandoned her workplace, and her stay will become illegal regardless of the circumstances.”[48]

In 2018, the South Korean government reported that it had enforced stricter criteria for the issuing of “entertainment visas” and that club owners with a previous criminal record of coercing and facilitating prostitution would not be authorised to sponsor visas for foreigners. However, a joint NGO submission to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) stated that these restrictions are easily circumvented. Indeed, club owners may continue to secretly employ workers under visa exempt or tourist visa status who are unable to report their working conditions, giving rise to potential conditions of sexual and/labour exploitation. Potential cases of exploitation are often only revealed during police raids or similar interceptions. Because potential victims of trafficking are initially identified in such cases as criminal suspects or witnesses, and identified as having violated the Immigration Act, they continue to face the risk of detention and deportation.[49]

There are also significant concerns regarding trafficking for labour exploitation in the fishery and aquaculture industry. In 2016, 70 percent of fishermen on Korean distant water fishing vessels were migrant workers. These workers often experience gruelling working conditions, given that there are no rules regarding the maximum number of working hours on such vessels. Moreover, their average wages are often significantly lower than that of their Korean counterparts, and there is also evidence that migrant fishermen have experienced physical abuse on these vessels. An NGO report also notes that migrant fishermen may be forced to remain on distant water fishing vessels offshore for long periods of time, with no means of outside communication; that recruitment companies may confiscate workers’ passports or travel documents and subject them to de facto detention at the Institute of Welfare and Education for Distant Water Migrant Fishermen; or that vessel owners may withhold payments to prevent migrant workers from leaving the workplace.[50] Various observers have criticised the government’s failure to identify victims of human trafficking and to provide them with sufficient protection, resulting in potential re-traumatisation.[51]

2.7 Length of detention. The maximum time for which non-citizens can be detained varies according the type of immigration-related detention.

2.7a Internment. Article 56 of the Immigration Control Act provides for the initial temporary internment of any non-citizen, for up to 48 hours, whose entry is not permitted under conditions of entry in Article 12(4); who has obtained a conditional entry permission under Article 13(1) and who has fled or appears very likely to flee; or who has obtained a deportation order and who has fled or appears very likely to flee.

Detention under an internment order is limited to 10 days, with the possibility of one extension of 10 days (Immigration Control Act, Article 51). When there is insufficient time to obtain an internment order, an immigration control official may issue an “emergency internment note” confining the person to an immigration office or foreigner internment camp (Article 51(3)). An internment order must then be obtained within 48 hours, otherwise the detained person is to be released (Article 51(4)).

2.7b Detention for deportation. Detention for deportation is not subject to a time limit (Immigration Control Act, Article 63(1)). Instead, Article 63(2) of the Immigration Control Act merely states that if the period of detention for deportation exceeds three months, the Minister of Justice must provide approval for every additional three months of detention—although the act does not specify the need to assess the necessity and reasonableness of detention, and observers have noted that the ministry instead purely grants extensions based on whether or not the individual can be deported.[52]

Numerous cases of individuals being detained for extended periods of time, in both immigration detention centres and in transit zone facilities, have been reported. A 2018 joint submission to CERD cites the case of one person who had been detained for six years.[53] In 2019, a family of six from Angola was detained for 287 days at Incheon International Airport before being released on a temporary stay visa.[54] (For more information, see: 2.8 Procedural standards).

2.7c Asylum detention. According to Article 20 of the Refugee Act, immigration officers may detain a refugee status applicant for 10 days for the purpose of verifying their identity, with an Order of Detention issued according to Article 51 of the Immigration Control Act. This initial period of detention may be extended by up to 10 days.

Article 6(2) of the Refugee Act also states that an applicant at a port of entry who is awaiting a decision on whether they will be referred to the RSD procedure may be required to “stay at a designated location within the port of entry for a period not exceeding seven days.”

Despite the Refugee Act’s provision of a time limit, refugee applicants have been detained without a time limit under provisions in the Immigration Control Act. In 2014, the average period of detention of refugee applicants was 100 days at Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre, 124 days at Cheongju Immigration Detention Centre, and 83 days at Yeosu Immigration Detention Centre.[55] In one case, a refugee applicant was detained for three years and nine months at Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre, which led him to develop suicidal tendencies and to lose most of his teeth due to severe stress. He was later recognised as a refugee and released from detention, but received no compensation.[56]

Numerous NGOs have criticised the government’s policy of indefinite detention.[57]

2.8 Procedural standards. There are four primary procedural safeguards provided in the Immigration Control Act: prior approval of the detention order by the Minister of Justice; the possibility of filing an objection to one’s custody; the possibility of requesting temporary release; and administrative litigation seeking revocation of the protection order.

Under the Immigration Control Act, the Minister of Justice must approve all detention orders as well as each successive three-month period (Article 63(2)). However, an Information Disclosure Request submitted by APIL found that between 2011 and 2014, only one detention order was cancelled due to absence of approval from the Minister of Justice. This case, which was assisted by APIL, concerned an applicant who was detained for 23 months at Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre, who was released from detention only after APIL found that the Minister of Justice’s decision was based on delayed paperwork (the Ministry of Justice issued its approval for the extension one day after the due date) rather than a judgment on the lawfulness of the detention. In its 2015 report to the HRC, APIL argued that “this procedure does not provide any effective review of the reasonableness, necessity, and proportionality of the detention by the independent body; it is rather reporting procedure to provide the reasons for delay of the execution of the deportation order.” The South Korea Human Rights Organizations Network (a group of 83 NGOs) referred to the prior approval process as a mere “administrative formality.”[58]

Article 55 of the Immigration Control Act allows a person who has been issued with a detention order to file an objection with the Minister of Justice through the head of the immigration services office or branch office, or the head of the detention centre. They may do so at any point of their detention. The head of the immigration services office or head of the detention centre must submit the applicant’s claim to the Minister of Justice together with the written examination, decision, and record of investigation. If the Minister of Justice decides that the objection is well-grounded, they will notify the head of the office or detention centre of the decision; if the individual has been detained, they should be released.

Article 65 of the Immigration Control Act provides any person to whom a detention order is issued with the possibility of requesting a temporary release from detention from the head of the office or branch office, or the head of the detention centre. (For more, see: 2.9 Non-custodial measures (“alternatives to detention.”))

APIL has criticised both the objection and the temporal release procedures because the criteria for accepting or rejecting both requests are unclear and depend on the discretion of the Minister of Justice. In addition, there are frequently delays in objection and temporal release decisions. APIL cites one case where it took more than 70 days to receive the result of an objection against a detention order.

Individuals detained under a detention order may also file for judicial review requesting cancellation of the detention order, in accordance with the Administrative Litigation Act.[59] The statute of limitations is 90 days from the day the person is notified of the initial detention order.[60] As APIL has highlighted, this option therefore prevents detainees, who have already been detained for more than 90 days, from challenging their detention—and thus precludes judicial reviews of extended detention.[61]

According to Article 2 of the Habeas Corpus Act, those who are detained according to the Immigration Act do not come under the category of “inmate” and thus cannot file a petition on this basis. In 2013, however, the issue as to whether refugee applicants at a port of entry may file for habeas corpus came to the fore when a Sudanese asylum seeker—denied entry to South Korea and access to a formal RSD procedure, handed a deportation order, and detained in a waiting room in Incheon International Airport—filed a petition. The individual stated that he had been forced to stay in a small room and provided with inadequate meals; at the same time, he sought revocation of the denial of referral to RSD. Although the Immigration Service argued that because the applicant was free to leave the room to return home, he was not “in detention,”[62] its reasoning was rejected by the Incheon District Court, which ordered the applicant to be released. Later, the Supreme Court found that “compelling even a foreigner, to whom entry was denied, to be held for a prolonged period in a confined space where entry and departure are controlled, constitutes an illegal confinement subject to relief under the Habeas Corpus Act, as a restriction of personal liberty without any legal grounds.”[63] As such, the court stated that the remedy of habeas corpus is applicable to asylum seekers who are confined in the waiting room of the international airport, if they are forced to do so by the immigration authority for an extended period of time without firm legal grounds. Nonetheless, the benefits of this remedy remain limited because asylum seekers released from the holding room would still only have access to a limited part of the airport until they are admitted into the country.

2.9 Non-custodial measures (“alternatives to detention”). Korean law does not explicitly mention non-custodial measures or “alternatives to detention.” However, it does provide detainees with an avenue to request relief from detention, which amounts to an “alternative” measure. Article 65 of the Immigration Control Act provides that any person who is issued a detention order can request temporary release from detention from the head of the office or branch office, or the head of the foreigner internment camp. Temporary release can be granted when a guarantor or legal representative applies and makes a deposit of guarantee money of up to 20 million KRW (approximately 17,000 USD), and with residence restrictions and other conditions (Immigration Control Act, Article 65).

2.10 Detaining authorities and institutions. The head of the Regional Immigration Service has the authority to issue a detention order (Immigration Control Act, Article 51). The Immigration Service may also require a person who has submitted an Application for Recognition of Refugee Status at the port of entry to stay at a “designated location” within the port of entry pending the result of their application (Refugee Act, Article 6). The Immigration Bureau, an agency of the Ministry of Justice, manages detention centres.

The director of the National Intelligence Service may detain a North Korean resident who applies for protection in South Korea (North Korean Refugees Protection and Settlement Support Act, Article 7). The director also determines the details and methods of detention, including the operation of the facilities used (Enforcement Decree of the North Korean Refugees Protection and Settlement Support Act, Article 12).

2.11 Regulation of detention conditions and regimes. In 2018, the Ministry of Justice passed the Regulations on the Protection of Foreigners. The Regulations established basic standards for detention facilities designated under Article 52 of the Immigration Control Act, including provisions regarding the special protection of migrant children, the treatment of detainees with mental health problems, separate facilities for different genders, and the types of material resources that are given to people in detention (such as food and clothing).[64]

2.12 Domestic monitoring. Both official and non-governmental entities visit immigration detention centres in South Korea.

Article 24 of the 2001 National Human Rights Commission Act provides that the NHRCK may visit all immigration facilities.[65] However, the UN Committee against Torture (CAT) has expressed concerns that Korean law “does not have provisions to ensure a clear, transparent, and participatory selection and appointment process for the members of the NHRCK.”[66]

In 2009, the NHRCK concluded that immigration arrest and detention procedures frequently violated provisions in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the UN Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment.[67]

In 2017-2018, after the NHRCK had visited Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre, Cheongju Immigration Office Detention Facility, and Yeosu Immigration Office Detention Facility, the commission renewed calls for improving respect for the human rights of immigration detainees. The committee recommended easing the carceral trappings of detention centres, taking steps to limit the use of solitary confinement, providing detainees with access to the internet, improving training of staff, and increasing exercise time, among other measures.[68]

Civil society organisations are also involved in monitoring immigration detention centres. In 2013-2014, the KBA conducted the first NGO-led, independent investigation into the conditions of immigration detention centres, including Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre, Cheongju Immigration Office Detention Facility, and Yeosu Immigration Office Detention Facility. The investigation revealed that conditions in immigration detention facilities were extremely poor.

A joint 2018 NGO submission to CERD reported that during the period 2012-2018, there had been numerous cases of migrant workers self-harming or being physically abused by immigration officers during enforcement procedures.[69]

In 2019, the KBA published a second report, with findings from Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre, Incheon International Airport Detention Facility, and Jeju International Airport Immigration Office Detention Facility. The conditions observed in Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre in 2019 showed improvement from those in 2014, such as installing narrow windows, improving ventilation, and removing the metal cell bars from family rooms (on recommendation of the NHRCK); however, there remained significant space for improvement (for more information, see: 3.3 Conditions and regimes in detention centres).[70]

2.13 International monitoring. Several international bodies monitor immigration detention practices in South Korea. From 2015 to 2019, four UN treaty bodies made recommendations regarding immigration detention in their concluding observations to South Korea. In 2015, the HRC recommended that the government limit the period of immigration detention and that conditions of detention are in conformity with international standards and subject to regular independent monitoring. The HRC also recommended that “defectors” from North Korea be detained for the shortest possible period, that they be given access to counsel during their time in detention, and that their conditions of detention comply with international human rights standards.[71]

Similarly, in 2017, the CAT recommended that South Korea establish a legally prescribed maximum duration of immigration detention and improve material conditions in immigration detention facilities, including ports of entry and departure. The CAT also recommended that North Korean residents seeking protection in South Korea only be detained for the shortest possible time and have access to all fundamental legal safeguards.[72]

In 2018, the CERD urged the government to ensure the lawfulness of the detention of migrants who cannot be deported is regularly reviewed by an independent mechanism; that the detention of asylum seekers should be considered only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest possible period; and that the government introduce a time limit for the detention of migrants, and prioritise the use of alternative measures to detention.[73]

UN treaty bodies have made several recommendations pertaining to the detention of migrant children. In 2011, the UN Committee for the Rights of the Child (CRC) called on the government to refrain from the detention of refugee, asylum-seeking, or unaccompanied children.[74] In 2015, the HRC recommended that the detention of migrant children only be used as a measure of last resort, for the shortest appropriate period.[75] In 2017, the CAT called on the government to avoid detaining immigrant minors and apply non-custodial measures to minors.[76] In 2018, the CERD called on the government to avoid detaining children and to amend the Immigration Act to include provisions related to the best interests of the child. [77]

In a marked shift in language, the CRC in 2019 urged the South Korean government to prohibit the immigration detention of children, including by revising the Immigration Control Act, ensure non-custodial solutions and keep the best interests of the child as a primary consideration in asylum and family reunification matters.[78]

2.14 Transparency and access to information. The Korean government does not disclose data regarding immigration detention. Although some statistics regarding the number of foreigners confined in prison are included in the Ministry of Justice’s annual reports, figures regarding administrative detention are not included. Reportedly, this is due to the fact that the Ministry of Justice does not conceive of immigration detention as “detention”—rather, it presents it as limited freedom of movement, and subsequently does not disclose data pertaining to such confinement.[79] An APIL lawyer told the GDP that when responding to freedom of information requests, officials have only provided partial data, such as statistics for individual detention centres. [80]

2.15 Trends and statistics. It is enormously challenging to assess trends in immigration detention in South Korea due to a lack of publicly available comprehensive statistics on this issue. Important sources for statistics are NGOs, though information they are able to provide is often relevant only to specific detention centres. For example, at the time of the writing of the KBA’s 2019 report, they reported that there were 262 people detained in Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre.[81] The KBA also reported that during its visit to the Incheon International Airport in January 2019, there were 31 people in the Deportation Waiting Room, 37 in the boarding wing, and six in the passenger terminal. [82] One news report notes that from 2012 to March 2015, 13,486 people had been detained at airport transit detention facilities after being refused referral to a formal RSD procedure.[83]

Some statistics appear to show a downward trend in certain forms of immigration detention. In particular, the number of people in long-term detention (more than six months) decreased from 44 in 2017 to 20 in 2018.[84] A lawyer for APIL told the GDP that this decrease “is not based on foreigners' human rights or systematic remedies, but is arbitrarily done by the immigration office.” He added that currently the Ministry of Justice “is taking an attitude of prompt deportation or using temporary release at its own discretion more frequently, to reduce the number of long-term immigration detainees.”[85]

2.16 Privatisation. According to observers, privatisation of immigration detention in Korea is limited to operations at airport detention rooms.[86] The Immigration Control Act provides that immigration officials may issue a detention order for foreign nationals at ports of entry if they are suspected of violating immigration rules or if it is deemed necessary to verify identity or nationality. The rooms used to confine people in these situations are leased by the government, which outsources their operation to a private company, Free Zone.[87]

Article 76 of the Immigration Control Act provides that after a removal order has been issued for an interned person, “the captain or the forwarder of the vessel … shall repatriate the foreigner without delay out of the Republic of Korea at their expense and responsibility.” Article 76(2) states that the head of the competent Immigration Control Office or the head of the competent branch office of the Immigration Control Office may, in times of necessity, establish a holding area at the entry port in which foreign nationals can reside prior to removal. Under such circumstances, unless there is a special reason to involve the head of office or the branch office in the provision of services to foreigners held in this area, the captain or relevant transportation business operator is responsible for such service provision.

At Seoul’s Incheon International Airport, the Airlines Operators Committee (AOC) (an organisation of 76 airlines operating at the airport)[88] leases a section of the passenger terminal to the Korean Immigration Service for the purposes of having a “Deportation Waiting Room.”[89] According to one news report, the Incheon International Airport Immigration Office held a meeting with the AOC in 2012 and said: “The Deportation Waiting Room will be operated and managed by the Incheon Airport Airline Operators’ Committee; the Incheon International Airport Immigration Office will simply pay the rent.”[90]

The private company Free Zone manages the waiting room for the operators committee; it also manages the waiting rooms at Jeju International Airport and Gimpu International Airport. In a 2016 interview, one staff member from Free Zone said that as workers, they received training in terms of safety and management, but no training about how to work with refugees.”[91]

The conditions of confinement at Incheon Airport have repeatedly drawn critical attention, both nationally and internationally. For instance, according to multiple news reports concerning the detention of 28 Syrian refugees in the waiting room in 2017, the detainees were unable to eat their meals because the meat was not halal, and they were only left with buns to eat during their lengthy detention.[92] A South Korean lawyer who is an expert in immigration matters told the Global Detention Project: “When people are not admitted to entry at the airport, they are taken to the waiting room until they are deported. … The facility remains locked and secured by private security guards employed by the Airline Operators Committee, most of whom do not speak English and are known for their mistreatment to detainees. Detainees are fed burgers three times a day for their meals and their requests for medical service are often neglected.”[93]

In September 2011, a U.S. citizen travelling from Honolulu to Mumbai was detained while trying to make a connecting flight in Seoul. In a lawsuit filed in Florida (Jacob v. Korean Air Lines Co. Ltd), the defendant claimed that he had been unlawfully detained by Korean Air (KAL) in the airport’s holding area, which was a contributing factor in alleged injuries he suffered. The Indian government had ordered KAL to return the passenger to the United States because he did not have adequate immigration papers. The lawsuit sought compensation under the Montreal Convention,[94] an international treaty that makes airlines liable for bodily injury caused by “accident” during international travel. Although the lawsuit was eventually dismissed and failed on appeal, the defendant’s detention at the hands of the airline company was not disputed.[95]

Although the Korean attorney who corresponded with the GDP said that the waiting room is ultimately under the “control of the immigration office of Korean government,” a U.S. attorney representing the defendant claimed that a Korean airlines manager told her firm that the facility was wholly operated by KAL and Asiana. She added that people detained at the facility “have a single shower, no soap, no towels, and no laundry facilities and they are being kept locked up by airlines who have no legal authority to hold them.”[96]

In a 2019 news report, a lawyer stated that asylum seekers who are not referred to the RSD at the port of entry suffer violence at the hands of airport authorities while being deported. He said: “They’re shot with gas pistols and put in handcuffs before being hauled onto a plane like luggage. In July 2018, there was one asylum seeker who’d been hit by a baton. As the asylum seeker cried and begged not to be beaten, the perpetrator looked on with a sneer on his face.”[97]

Scholars of immigration detention systems have highlighted Incheon airport as an example of non-state actor involvement in immigration detention systems. According to one account, “The Incheon airport case is an example of the larger phenomenon of the outsourcing of immigration controls that has resulted from the application of ‘carrier sanctions,’ in which private transport companies are held accountable and become the de facto custodial authorities for people they transport who are refused admission at their destinations.”[98]

One result of this form of detention is that it can artificially shield states from providing access to fundamental rights, including the right to seek asylum. “The effort to block asylum seekers from boarding planes or entering national territory has resulted in private companies serving as de facto arbiters of asylum as airlines are pressured to deny passage to certain people, which can lead to violations of non-refoulement. On the one hand, as scholars have noted, state responsibility in such cases can be interpreted narrowly so that the state is not held accountable for the rejection of asylum seekers on another state’s territory; however, it may be impossible to hold the airline accountable for a violation, particularly in extraterritorial cases.”[99]

3. DETENTION INFRASTRUCTURE

3.1 Summary. There are a number of types of facilities in the Republic of Korea that serve immigration detention roles. These include dedicated immigration detention centres (called “processing centres”), detention cells at immigration branch offices, and transit facilities at ports of entry. These facilities are under the overall authority of the Immigration Bureau—an agency of the Ministry of Justice. Formally, airport transit zones are leased to and operated by private companies, but decisions regarding the detention of foreigners in these transit zones are made by the Immigration Bureau.

In addition to these immigration-related detention sites are facilities that are used to confine, in certain cases, North Korean defectors as part of “provisional protective measures.” This section of the report does not detail operations at those facilities. (For more information concerning these measures, see: 2.2c “Provisional measures” for North Koreans and 2.4b North Korean “defectors” above).

As of February 2020, the Immigration Bureau maintained three detention centres (in Hwaseong, Yeosu, and Cheongju), which are used exclusively for detention purposes.[100] It also maintains detention cells in at least 16 branch offices: Seoul, Incheon, Incheon International Airport, Busan, Suwon, Jeju, Seoul Southern, Daegu, Daejeon, Yangju, Ulsan, Gwangju, Changwon, Jeonju, Chuncheon, and Cheongju.[101]

In addition, transit-zone detention sites are located in Incheon International Airport, Jeju International Airport, Gimhae International Airport, and Gimpu International Airport. In Incheon International Airport, the Korean Immigration Service leases part of the passenger terminal from the Airline Operators’ Committee to establish a Deportation Waiting Room. According to the government, the Deportation Waiting Room operates as “‘as an open facility with free access,’” which people can apply to use. According to one source interviewed by the GDP, this facility is used to prevent people from entering Korean territory and there are many cases in which people have been held at this site for periods for extended periods of time.[102] The same source said that there has been at least one case in which a person was “detained” by an airline at the airport because immigration authorities said the inadmissible person was the responsibility of the airline. The person was kept for an unknown period of time at an undisclosed location at the airport until the airline was able to put the person on a flight leaving the country.[103]

South Korea uses three prisons for holding non-citizens for minor criminal offences: male non-citizens whose convictions have been confirmed are held exclusively at Daejeon Prison and Cheonan Prison, and women are confined at Cheongju Women’s Prison. Meanwhile, non-citizens whose criminal procedures are ongoing are held in prisons across the country (for more information, see: 2.3 Criminalisation).[104]

3.2 List of detention facilities. The following facilities have been reported as operational as of February 2020: Hwaseong Immigration Processing Centre/Immigration Detention Centre, Cheongju Immigration Processing Centre/Immigration Detention Centre, Yeosu Immigration Office Detention Facility, Incheon International Airport Deportation Waiting Room, Jeju International Airport Deportation Waiting Room, Gimhae International Airport Deportation Waiting Room, Gimpo International Airport Deportation Waiting Room, detention cells in branch offices in Seoul, Incheon, Incheon International Airport, Jeju, Busan, Daegu, Ulsan, Gimhae, Masan, Cheongju, Daejeon, Chuncheon, Suwon, Gwangju, Jeonju, and Yeosu.[105]

3.3 Conditions and regimes in detention centres.

3.3a Overview. Human rights groups have long documented the poor conditions in Korea’s detention facilities, including the employment of private security guards and public service personnel without training;[106] instances of physical and verbal abuse; overcrowding and poor sanitation; insufficient exercise; restricted communication with the outside world (including minimal visitor accessibility and in some cases censorship of detainee letters); and lack of privacy and constant camera surveillance.[107] In addition, during the investigation process, detainees were sometimes denied access to interpreters and forced to sign documents in a foreign language.[108]

After a deadly fire claimed the lives of 10 detainees and injured many others in Yeosu Immigration Office Detention Facility in 2007, many NGOs criticised the conditions at the country’s detention centres.[109] The NHRCK conducted an investigation into the fire and found that the deaths incurred constituted a grave violation of human rights. Subsequently, it urged the Minister of Justice to improve the professionalism of guards working at immigration detention centres and to formulate safety measures and practical training for those detained in such centres. It stated that “such accidents as the fire at the Yeosu Immigration Office can hardly be prevented without fundamental improvement in institutional schemes and practices of the agencies concerned regarding their overall foreigner custody system.”[110]

Since the fire, piecemeal efforts have been made to improve detention facilities. For example, as of 2019, Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre had removed steel bar dividers from its facility––although NGOs and the NHRCK have been advocating for this recommendation to be implemented across all detention centres in the country since 2012.[111] There remains significant space for improvement in different facilities, such as in the areas of hygiene, medical care provision, ventilation, and access to Internet and phones. [112]

Airport transit zones are particularly ill-equipped for long-term detention. In these zones, detainees’ passports are confiscated so that they are unable to leave the airport; they also have limited freedom of movement within the airport.[113] While people with a deportation order may technically leave the allocated Deportation Waiting Room to other parts of the airport, NGOs report that non-nationals who decide not to stay in the Deportation Waiting Room are not allowed to re-enter, nor are they given the free meals offered to those inside the room. They must find their own meals or rely on the donations of other passengers in the airport. In effect, the waiting room structure forces non-citizens to choose whether to accept restrictions on their freedom of movement in exchange for the state fulfilment of daily needs; or to attempt to fulfil those needs themselves, with no financial support.[114] Those staying in the Deportation Waiting Room may also be unable to exercise their right to an attorney.[115]

According to the Immigration Control Act, applicants awaiting the results of the refugee referral procedure at the port of entry should be kept in a separate waiting room to those awaiting deportation. In practice, however, there is often only one waiting room for both groups of people, such as in Jeju International Airport. [116]

3.3b Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre. Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre is the largest immigration detention facility in South Korea. More than 105,000 people were detained here from 2017 to 2019.[117]

A 2019 report from the KBA notes that some improvements were made to the facility after the KBA’s last inspection in 2013-2014, including improving ventilation facilities in the living area, ameliorating bathroom facilities, and installing underfloor heating. The centre also followed the NHRCK’s recommendation to remove metal bars from its family rooms.[118]

However, there remain areas of significant concerns regarding the treatment of detainees at Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre. In particular, the KBA noted the growing exhaustion on the part of staff members at the centre, which may lead to deteriorating living conditions for detainees; a lack of interpretation services during medical check-ups; and insufficient mental health care provisions.[119]

There have also been multiple reported cases of ill-treatment in Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre. A 2018 joint NGO submission to the CERD criticised the centre for failing to provide appropriate medical assistance to detainees, referring to the case of one Pakistani national who contracted an infectious disease and was left untreated throughout his 26 months in detention.[120] In 2017, a migrant worker from Uzbekistan detained in Hwaseong Immigration Detention Centre went on hunger strike and attempted to commit suicide, but was subsequently deported.[121]

3.3c Yeosu Immigration Office Detention Centre. The Yeosu Immigration Office Detention Centre is well known as the site of a notorious incident in February 2007, when a fire at the facility killed 10 detainees and left many wounded. Detention centre staff were criticised for reportedly spraying fire extinguishers through cell bars and not unlocking cell doors to let detainees escape. Neither the alarm system nor the sprinklers functioned properly. The flooring inside each cell, which were reportedly made with the toxic chemical urethane, caught on fire, releasing noxious fumes. This incident caused public outrage, and was investigated by the NHRCK, which issued a series of recommendations on detention centre reform in an April 2008 report.[122]

Ten years later, according to media outlets, conditions at the detention centre have improved. The urethane flooring has been replaced with a non-flammable material; sprinklers have been installed across the entire facility; additional fire extinguishers, fire hoses, and gas masks have been added, as well as 224 fire detectors (including 177 thermal detectors). Other improvements implemented in the facility include: the installation of a ventilator in the guardhouse; the addition of an emergency key to the guardhouse; and the addition of an automatic door and emergency exit lights in the guardhouse. Staff members are now provided with guidebooks for handling fires, incidences of escape, demonstrations, and outbreaks of disease.

3.3d Incheon Airport Transit Zone. At Incheon Airport, people with a deportation order, including those with rejected claims for refugee status, have two options as to where they can stay: a secure Deportation Waiting Room or the passenger terminal. The Deportation Waiting Room is a space in the airport leased to the immigration control office by the Airlines Operators’ Committee, and is managed by the private company Free Zone. It has separate sleeping areas for men and women. There is also a general living area, with a TV, payphone, and free Wifi. There are male and female bathrooms, two showers, a smoking area, and water and air purifiers.

Free Zone provides three daily meals to those staying in the Waiting Room. Each meal is reportedly comprised of a hamburger and a drink. A 2017 report on 28 Syrian refugees who were detained in the Waiting Room indicated that the hamburger provided did not use halal meat, meaning that some people could only eat the bun.[123] Women must pay separately for sanitary products, and families with babies must also pay separately to order milk powder and other special meals.[124] There are no family or child-friendly facilities in the Deportation Waiting Room.

One NGO report states that in practice, foreigners in the deportation room often do not have freedom to leave the room. According to data provided by the Ministry of Justice, from 31 December 2014 to 31 August 2015, only 68 out of 17,891 people were allowed to leave the Deportation Waiting Room for reasons other than deportation: 49 were released after their refugee application was accepted, and 19 were allowed to leave under the Urgent Landing Permission.[125]

It is not mandatory for people with a deportation order to stay in the Deportation Waiting Room at Incheon Airport. However, once an individual leaves, they can no longer re-enter, and lose access to the free meals provided by the service company. Those who choose to live in other parts of the passenger terminal may access the showers and hotel rooms of the airport; however, they must pay for their own meals. In 2019, a family of six from Angola whose referral to RSD was rejected decided to leave the room and stay in other parts of the passenger terminal instead. Staff members of the Deportation Waiting Room continued to provide them with free meals when conducting routine check-ups.

According to APIL, the private security guards working in Incheon International Airport Deportation Waiting Room “often insult the detainees with the racist insults, ignorance, and criminal-like treatment.”[126]

3.3e Jeju International Airport Deportation Waiting Room. Free Zone also manages the Jeju International Airport Deportation Waiting Room. The room has separate sleeping areas for men and women. There are male and female bathrooms, with one shower each. There are no laundry facilities, and towels and toothbrushes are not provided. One detainee said that when they asked for a towel, they were told by detention centre staff to use paper towels to wipe themselves dry.[127]

The Deportation Waiting Room has a payphone and Wifi. Regarding meals, those detained in the room can order different items from a menu, the cost of which is covered by Free Zone. During meals, a table is set up in the Deportation Waiting Room so that all the detainees can eat together.[128] Women must pay separately for sanitary products; families must also pay separately for milk powder and baby products. On some occasions, detention centre staff have provided families with supplies on their own volition. There are no separate facilities for families or children.[129]

The majority of staff working in the room are women; however, there are insufficient staff members to monitor the centre. As a result, male detainees may sometimes enter the designated women’s room, which causes anxiety and concern on the part of female detainees. [130]

The KBA reported although emergency sprinklers are installed in the room, there is insufficient guidance on what to do in cases of emergency.[131]

Unlike Incheon International Airport, Jeju International Airport does not have a separate room for refugee claimants awaiting the results of their claim. This means that refugee applicants awaiting the results of their claim must stay in the same place as those with a deportation order.[132]

The Global Detention Project would like to acknowledge the assistance we received from GDP Research Fellow Jun Pang in the production of this report, as well as the feedback we received from reviewers in South Korea, in particular IL Lee of Advocates for Public Interest Law.

[1] IL Lee (Advocates for Public Interest Law), Comments on Draft GDP South Korea Profile/Email Correspondence with Michael Flynn (Global Detention Project), 20 February 2020; South Korean NGO Coalition, “Republic of Korea NGO Alternative Report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination,” Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, November 2018, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/KOR/INT_CERD_NGO_KOR_32854_E.pdf. SEE ALSO: W.B Kim, “Migration of Foreign Workers into South Korea: From Periphery to Semi-Periphery in the Global Labor Market,” Asian Survey 44(2), 2004; S. Lee, ”The Realities of South Korea’s Migration Policy,” Monterey Institute of International Studies, 2003.

[2] National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK), “Findings of On-site Investigations into Immigration Detention Centers,” 22 January 2009, http://www.humanrights.go.kr/english/activities/view_01.jsp

[3] National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK), Press Release: Recommendations for Improving Human Rights in Immigration Detention Centres, 4 February 2018, https://www.humanrights.go.kr/site/program/board/basicboard/view?boardtypeid=24&boardid=7602610&menuid=001004002001 (in Korean)

[4] Korean Immigration Service, “Notice on the Illegal Employment and Voluntary Departure of Foreigners,” Embassy of the Republic of Korea in the Republic of the Philippines, 2 October 2019, https://bit.ly/2vWQRC2

[5] M. Kunthear, “South Korea Issues Ultimatum to Illegal Migrants,” Khmer Times, 17 October 2019, https://www.khmertimeskh.com/541169/south-korea-issues-ultimatum-to-illegal-migrants/

[6] C. Ji-won, “Kazakh Man Suspected of Hit-and-Run Extradited to Korea,” The Korea Herald, 14 October 2019, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20191014000685&ACE_SEARCH=1

[7] Yonhap News, 28 May 2019, https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20190527147000371 (in Korean)

[8] Yonhap News, 28 May 2019, https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20190527147000371 (in Korean)

[9] Korean Joongang Daily, “16,613 Refugee Claimants in 2018,” 20 June 2019, https://news.joins.com/article/23502147 (in Korean)

[10] K. Min-Sang, “16,613 Refugee Claimants in 2018, 62.7% Increase Year on Year,” JoongAng Ilbo, 20 June 2019, https://news.joins.com/article/23502147

[11] Ministry of Justice, “Special Entry Arrangements for Jeju Island (Visa-free entry),” Embassy of the Republic of Korea in Malaysia, 6 April 2018, https://bit.ly/3a3XRff

[12] C. Sang-Hun, “South Korea Denies Refugee Status to Hundreds of Fleeing Yemenis,” The New York Times, 17 October 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/17/world/asia/south-korea-yemeni-refugees.html

[13] South Korean NGO Coalition, “Republic of Korea NGO Alternative Report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination,” Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, November 2019, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/KOR/INT_CERD_NGO_KOR_32854_E.pdf

[14] O. Hyun-ju, “Jeju Refugee Crisis and Beyond: Yemeni Asylum Seekers Build Life in Korea,” The Korea Herald, 17 February 2019, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20190217000042

[15] IL Lee (Advocates for Public Interest Law), Comments on Draft GDP South Korea Profile/Email Correspondence with Michael Flynn (Global Detention Project), 20 February 2020.

[16] IL Lee (Advocates for Public Interest Law), Comments on Draft GDP South Korea Profile/Email Correspondence with Michael Flynn (Global Detention Project), 20 February 2020.

[17] IL Lee (Advocates for Public Interest Law), Comments on Draft GDP South Korea Profile/Email Correspondence with Michael Flynn (Global Detention Project), 20 February 2020.

[18] Korean Bar Association, “Alternative Report Submitted to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD),” UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 5 November 2018, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/KOR/INT_CERD_NGO_KOR_32994_E.pdf

[19] S. Kim, “One Year after the Korean Refugee Act,” RefLaw, 7 January 2015, http://www.reflaw.org/one-year-after-the-korean-refugee-act/

[20] UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), “Concluding Observations on the Fourth Periodic Report of the Republic of Korea,” 3 December 2015, https://bit.ly/39YIOmT

[21] Ministry of Justice, “2018 Statistical Yearbook,” http://www.korea.kr/archive/expDocView.do?docId=38172

[22] Pill Kyu Hwang, (Korean Public Interest Lawyers Group GONGGAM), Telephone interview with Michael Flynn (Global Detention Project), 3 June 2009.

[23] Il Lee (Advocates for Public Interest Law), Email correspondence with Michael Flynn (Global Detention Project), February 2020.

[24] South Korean NGO Coalition, “Republic of Korea NGO Alternative Report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination,” Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, November 2019, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/KOR/INT_CERD_NGO_KOR_32854_E.pdf

[25] South Korean Human Rights Organizations Network, “Joint NGO Submission to the Human Rights Committee for Lists of Issues Prior to Reporting, Republic of Korea, 126th Session,” UN Human Rights Committee, May 2019, https://bit.ly/38YUjuw

[26] K. Ji-dam, “Refugee Applicants Abused and Harassed by Airport Authorities,” Hankyoreh, 21 June 2019, http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/898852.html

[27] S. Kim, “Denial at the Airport, Denial of Procedural Fairness: Examining the Korean Refugee Act,” RefLaw, 27 March 2017, http://www.reflaw.org/denial-at-the-airport-denial-of-procedural-fairness-examining-the-korean-refugee-act/

[28] South Korean Human Rights Organizations Network, “Joint NGO Submission to the Human Rights Committee for Lists of Issues Prior to Reporting, Republic of Korea 126th Session” UN Human Rights Committee, May 2019, https://bit.ly/37NcfXG

[29] Nancen, “National Refugee Statistics (until 31 December 2018),” 28 May 2019, https://nancen.org/1938?category=118980

[30] National Human Rights Commission of Korea, “Information to the UN Human Rights Committee for the adoption of the List of Issues Prior to Reporting in relation to the consideration of the Fifth Periodic Report by the Government of Republic of Korea,” UN Human Rights Committee, May 2019, https://bit.ly/2SRj9XE

[31] South Korean NGO Coalition, “Republic of Korea NGO Alternative Report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination,” UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, November 2019, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/KOR/INT_CERD_NGO_KOR_32854_E.pdf

[32] National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK), “Information to the UN Human Rights Committee for the Adoption of the List of Issues Prior to Reporting in relation to the consideration of the Fifth Periodic Report by the Government of Republic of Korea,” UN Human Rights Committee, May 2019, https://bit.ly/2PlPKTf