In the morning of Saturday 8 April, a male immigration detainee was found unconscious in his cell in Geneva’s Favra detention facility. His death has prompted renewed calls for authorities to close the controversial centre. According to a press release from the Department of Security, Population and Health (DSPS), the man (reportedly a Tunisian awaiting […]

Switzerland: Covid-19 and Detention

In early May 2021, the Swiss immigration authority (Secrétariat d’Etat aux Migrations or SEM) launched an investigation into allegations of violence at federal asylum centres in Switzerland. The investigation followed the release of press reports about the use of excessive force by security officers when dealing with some asylum seekers. According to SEM, appropriate procedures […]

Flughafengefängnis, Boudry et Kantonaler Polizeiposten Flughafen In Switzerland (From the report of the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture 2021 visit to Switzerland)

E. Personnes faisant l’objet de mesures de contrainte en matière de droit des étrangers, (Read full CPT report) 236. Le CPT a examiné la situation des étrangers détenus en vertu de la législation sur les étrangers lors de sa visite en Suisse en 2007158. Au cours de la visite de 2021, la délégation a effectué […]

Switzerland: Covid-19 and Detention

On 26 January 2021, the SRF/RTS reported that the Asylum Departure Centre in Aarwangen was placed under quarantine by the Canton of Bern because 19 of its 100 inhabitants had tested positive for COVID-19. They also closed the facility’s kindergarten and school. On 29 January 2021, the Canton reported that the number of positive cases […]

Switzerland: Covid-19 and Detention

In a recent finding, the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) concluded that Switzerland violated provisions in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child when it failed to show due diligence in assessing a child’s best interests and did not take the child’s views into account in a case involving a […]

Switzerland: Covid-19 and Detention

As the GDP previously reported (see 27 June update), while Swiss authorities did not issue a moratorium on new detention orders during the pandemic, many immigration detainees were released due to the impossibility of conducting returns. This has been confirmed by Amnesty International Switzerland, which informed the GDP that some cantons declared a moratorium on […]

Switzerland: Covid-19 and Detention

Responding to the Global Detention Project Covid-19 survey, AsyLex reported that although Switzerland has not established a moratorium on new immigration detention orders, many immigration detainees have been released because returns are no longer possible. Certain local governments (cantonal authorities) have released all detainees, confirming information provided to the GDP by the Director General of […]

Switzerland: Covid-19 and Detention

Responding to the Global Detention Project’s Covid-19 survey, the Geneva Cantonal Population and Migration Office (Office Cantonal de la Population et des Migrations or OCPM) reported that while Geneva had not established a moratorium on new immigration detention orders, no new orders have been issued since the end of April, owing to the impossibility of […]

Switzerland: Covid-19 and Detention

Since the beginning of April, certain immigration detention centres, including the Frambois and Favra centres in Geneva, have been closed. Around 30 people were detained in the centres at the time. Reports suggest that they may have been assigned to a temporary residence or may be prohibited from entering a specific perimeter or region. The […]

Switzerland: Covid-19 and Detention

Swiss authorities have temporarily closed some immigration detention facilities, and detainees who have contracted the virus have been placed in isolation in prisons. In the early stages of the virus’ spread within the country, three Covid-19 cases were detected within federal asylum centres (Chevrilles, Basel, and Bern). Transfers between such facilities were subsequently reduced, but […]

Last updated: June 2020

DETENTION STATISTICS

Reported Detainee Population (Day)

DETAINEE DATA

DETENTION CAPACITY

ALTERNATIVES TO DETENTION

ADDITIONAL ENFORCEMENT DATA

PRISON DATA

POPULATION DATA

SOCIO-ECONOMIC DATA & POLLS

LEGAL & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

Does the Country Have Specific Laws that Provide for Migration-Related Detention?

Bilateral/Multilateral Readmission Agreements

GROUNDS FOR DETENTION

Immigration-Status-Related Grounds

Criminal Penalties for Immigration-Related Violations

Grounds for Criminal Immigration-Related Incarceration / Maximum Length of Incarceration

Has the Country Decriminalised Immigration-Related Violations?

LENGTH OF DETENTION

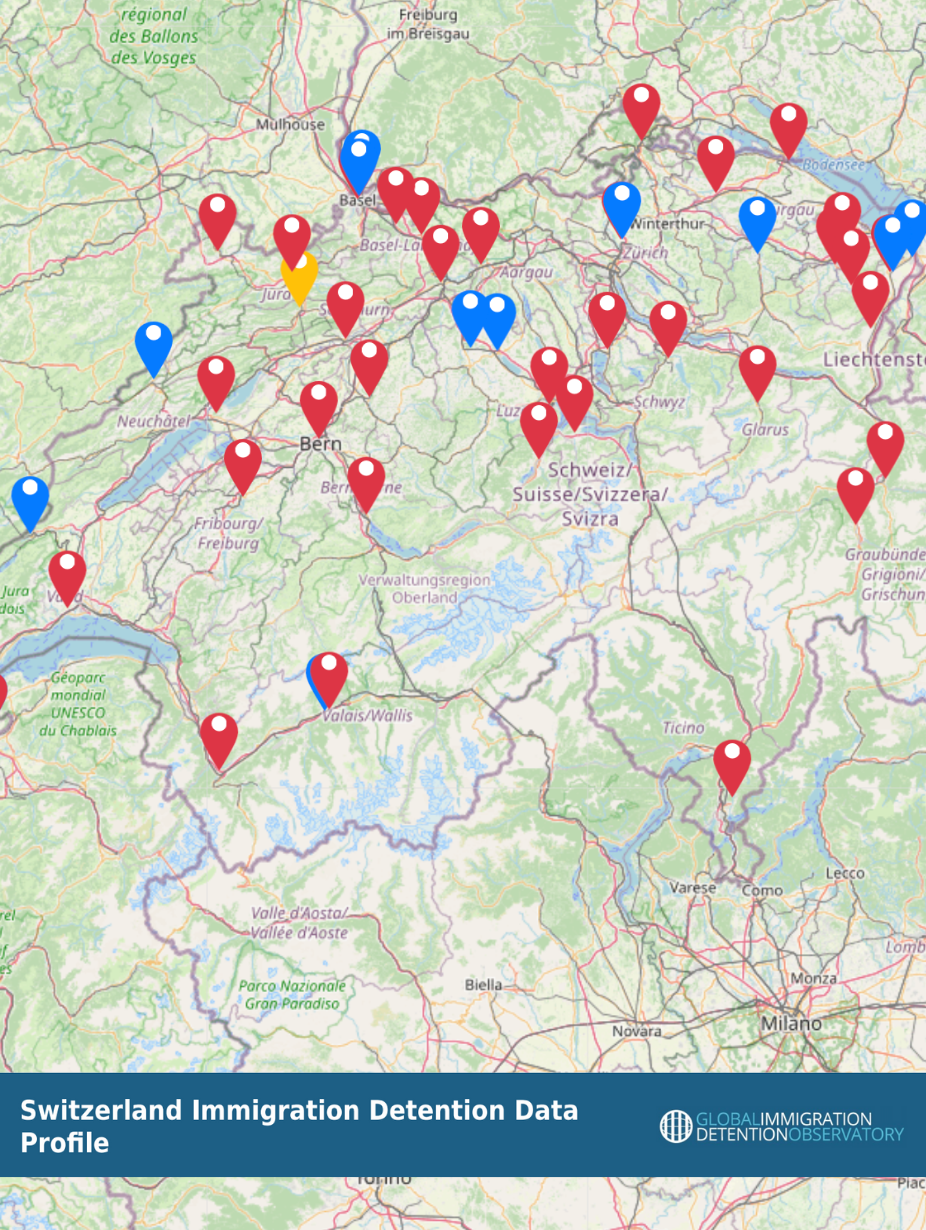

DETENTION INSTITUTIONS

Custodial Authorities

Detention Facility Management

PROCEDURAL STANDARDS & SAFEGUARDS

Types of Non-Custodial Measures (ATDs) Provided in Law

COSTS & OUTSOURCING

COVID-19 DATA

TRANSPARENCY

MONITORING

Types of Authorised Detention Monitoring Institutions

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MONITORING BODIES

NATIONAL PREVENTIVE MECHANISMS (OPTIONAL PROTOCOL TO UN CONVENTION AGAINST TORTURE)

NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS (NGOS)

GOVERNMENTAL MONITORING BODIES

INTERNATIONAL TREATIES & TREATY BODIES

International Treaties Ratified

Ratio of relevant international treaties ratified

Relevant Recommendations or Observations Issued by Treaty Bodies

(a) Strictly limit the use of administrative detention to that which is necessary

and proportionate, including by reducing the maximum length of administrative

detention of asylum-seekers under the Asylum Act to as short a period as possible,

taking all measures necessary to avoid the detention of children placed in migration

detention facilities, including by using alternatives to detention, and in no case imposing

measures or conditions designed to induce persons at the facilities to take any steps that

would jeopardize their rights or interests;

(b) Ensure the reform of the reportedly prison-like environment of administrative detention facilities, which includes limitations on visitation rights and confiscation of personal belongings;

(c) Guarantee that administrative detainees have access to legal representatives while in detention;

(d) Ensure consistency in the application of administrative detention by all cantons.

30. The State party should:

(a) Ensure that all instances of alleged ill-treatment at federal asylum centres

are promptly investigated in an independent and impartial manner and that the

suspected perpetrators are duly tried and, if found guilty, punished in a manner

commensurate with the gravity of their acts and that victims obtain adequate redress

and compensation;

(b) Enhance and strengthen independent safeguarding and proactive

monitoring at federal asylum centres;

(c) Establish independent, confidential and effective complaints mechanisms

at all federal asylum centres;

(d) Review the practice of locking individuals held at federal asylum centres in “reflection rooms”, including by prohibiting the placement of minors in isolation;

(e) Ensure that, if it is intended that private security contractors are to continue to play a role at federal asylum centres, they do not carry out sensitive security tasks, integrate stricter requirements concerning quality standards and training into their contracts and ensure that security contractors recruit experienced and skilled security personnel and that they train them specifically for assignments at federal asylum centres.

32. The State party should uphold the principle of the best interests of the child in

repatriation procedures and ensure that all unaccompanied minors, in particular girls,

receive ongoing care and protection and that reports of child disappearances during the

asylum procedure are investigated.

individual assessment of the risk of any person becoming a victim of enforced

disappearance is conducted before it proceeds with an expulsion, return, surrender or

extradition, including in cases where entry is refused at an airport or at the border. In

the case of a person from a State considered “safe”, the risk of him or her subsequently

being transferred to a State where he or she might be at risk of enforced disappearance

should also be assessed. In this regard, the Committee recommends improving the

training provided to staff involved in asylum, return, surrender or extradition

procedures and, in general, to law enforcement officials, on the concept of “enforced disappearance” and on the assessment of the related risks...

38. The Committee recommends that the State party: (a) review the number of

asylum applications discontinued on account of the disappearance of unaccompanied

juvenile applicants; (b) conduct thorough investigations into these cases, including by

making use of mutual legal assistance with States experiencing the same phenomenon;

(c) undertake searches to locate the missing minors; and (d) adopt new measures to

prevent the disappearance of unaccompanied minors from reception centres, in

particular by drawing on the good practices adopted by other States

<p>§ 17: The State party must also take measures to ensure that minors and adults, as well as detainees serving under different prison regimes, are separated. Finally, it must take steps to ensure the application of legislation and procedures concerning health-care access for all prisoners, especially those with psychiatric problems.</p>

68. While welcoming the entry into force in 2014 of the revision of the Asylum Act which requires priority treatment of asylum applications from unaccompanied children, the Committee remains concerned that the asylum procedure for unaccompanied children is not always guided by their best interests and, in relation to the reservation made to article 10 of the Convention, that the right to family reunification for persons granted provisional admission is too restricted. Moreover, the Committee is concerned that:

(a) Considerable cantonal disparities exist in relation to reception conditions, integration support and welfare for asylum-seeking and refugee children, with children being placed in, for instance, military or nuclear bunkers;

(b) “Persons of trust” for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children are not required to be experienced in child care or child-rights matters;

(c) Asylum-seeking children face difficulties in accessing secondary education and there is no harmonized practice in granting authorizations for them to take up vocational training;

(d) The accelerated asylum procedure, which is also carried out at airports, may be applied to children;

(e) A considerable number of sans-papiers children (children without legal residence status) live in the State party and they face many difficulties in accessing, inter alia, health care, education, in particular secondary education, and vocational training, and there is a lack of strategies on how to address these issues...

69. The Committee recommends that the State party:

(a) Ensure that the asylum procedure fully respects the special needs and requirements of children and is always guided by their best interests;

(b) Review its system for family reunification, in particular for persons granted provisional admission;

(c) Apply minimum standards for reception conditions, integration support and welfare for asylum seekers and refugees, in particular children, throughout its territory , and ensure that all reception and care centres for asylum-seeking and refugee children are child-friendly and conform to applicable United Nations standards;

(d) Ensure that “persons of trust” are properly trained to work with unaccompanied asylum-seeking children;

(e) Ensure that asylum-seeking children have effective and non-discriminatory access to education and vocational training;

(f) Exempt unaccompanied asylum-seeking children from the accelerated asylum procedure and establish safeguards to ensure that the right of the child to have his or her best interests taken as a primary consideration is always respected;

(g) Develop policies and programmes to prevent the social exclusion of and discrimination against sans-papiers children and allow these children to fully enjoy their rights, including by ensuring access to education, health care and welfare services in practice."

(a) Ensure that authorities in charge of asylum procedures comply with the right of the child to have his or her best interests taken as a primary consideration in all decisions related to the transfer, detention or deportation of any asylum-seeking or refugee child, including by: (i) developing a procedure for assessing and determining the best interests of the child in all asylum processes; (ii) strengthening coordination between the asylum system and the child protection system and ensuring that child protection professionals are involved in such decisions; and (iii) exempting children from the accelerated asylum procedure;

[...]

(h) Ensure that children under the age of 18 are not detained because of their migration status;

[...]

> UN Special Procedures

> UN Universal Periodic Review

Relevant Recommendations or Observations from the UN Universal Periodic Review

39.316 Guarantee minimum standards that take into account the specific needs of refugees, asylum-seekers and unaccompanied and separated children in federal and cantonal asylum reception centres (Colombia);

REGIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MECHANISMS

Regional Legal Instruments

Relevant Recommendations or Observations of Regional Human Rights Mechanisms

Les autorités valaisannes indiquent que le Centre de détention administrative (CDA) a effectivement ouvert en juin 2024, sur le même site que la prison de Sion. Cependant, il ne s'agit pas d'une extension mais d'un établissement indépendant répondant en tous points aux critères énoncés par la LEI. Durant la phase de projet, l'OFJ a validé le concept de construction du CDA. Un soin particulier a été apporté afin de réduire au maximum le caractère carcéral des locaux. Les personnes détenues bénéficient d'une liberté de mouvements accrue, des activités occupationnelles sont proposées du lundi au vendredi et les contacts avec l'extérieur sont possibles quotidiennement, que ce soit par le biais de visites, de téléphones ou de vidéoconférences.

107. Le CPT recommande aux autorités vaudoises de prendre les mesures qui s’imposent afin de revenir à la capacité initiale de la prison du Bois-Mermet et de dédoubler l’occupation des cellules doubles et quadruples. De plus, il réitère sa recommandation de cloisonner complètement l’espace sanitaire dans les cellules occupées par plusieurs détenus.

rapidement les ressortissants étrangers qui font l'objet de mesures de contrainte en vertu de la

législation sur les étrangers dans des centres spécifiquement conçus pour la détention

administrative et pour éviter leur détention en milieu carcéral. Jusqu'à leur transfert, il

convient de s'assurer que les personnes concernées bénéficient de conditions matérielles et d'un

régime appropriés, lorsqu'il n'existe pas d'alternatives à leur placement exceptionnel en milieu

carcéral.

-- Le Comité souhaiterait également recevoir des informations actualisées sur les projets

d'augmentation du nombre de places dans les centres dédiés à la détention administrative, ainsi

que des données statistiques précises sur la capacité globale des lieux de détention

administrative dans toute la Confédération, tant dans les centres dédiés que dans les

établissements pénitentiaires.

-- En outre, le CPT recommande aux autorités suisses de poursuivre leurs réflexions sur les

alternatives possibles à la privation de liberté afin de permettre leur application en pratique

pour éviter le recours à la détention administrative des ressortissants étrangers.

242. Le CPT souhaiterait recevoir des informations actualisées sur les travaux de rénovation prévus.

245. Le CPT souhaiterait être informé du nombre de cas où des demandeurs d'asile ont été hébergés au CFA de Boudry pour des périodes supérieures à 140 jours pour les années 2020 et 2021 et leur justification.

246. Le CPT souhaiterait être informé en détail de toutes les mesures prises par le SEM concernant le CFA de Boudry, y compris les résultats des enquêtes ouvertes.

247. Le CPT souhaiterait recevoir le nombre d'incidents enregistrés concernant des

allégations d'usage excessif de la force au CFA de Boudry pour les années 2019, 2020 et 2021 et

savoir si certains de ces incidents ont donné lieu à des procédures disciplinaires ou pénales.

-- En outre, le Comité souhaiterait recevoir des commentaires des autorités sur les

allégations des demandeurs d'asile concernant le harcèlement sexuel par des agents de sécurité.

248. Le CPT souhaiterait être informé du nombre de décès en détention depuis l'ouverture

du CFA de Boudry171, ainsi que des mesures qui ont été prises pour enquêter sur la cause des

décès.

250. Le CPT recommande aux autorités du canton de Zurich

d'appliquer le régime des neuf heures d'ouverture des portes également le mercredi et pendant

les week-ends au Centre de détention administrative de l'aéroport de Zurich.

251. Le Comité encourage les autorités du canton de Zurich à permettre aux personnes

détenues au centre de détention administrative de l'aéroport de Zurich de bénéficier d’au moins

deux heures par jours d’exercice en plein air.

HEALTH CARE PROVISION

HEALTH IMPACTS

COVID-19

Country Updates

Government Agencies

State Secretariat of Migration - https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/en/home.html

Federal Department of Justice and Police - https://www.migration.swiss/en/stories/zuwanderung

Office Cantonal de la Polpulation et des imgrations (OCPM) - https://www.ge.ch/organisation/office-cantonal-population-migrations-ocpm

International Organisations

UNHCR Country office - https://unrefugees.ch/fr

IOM Country office - https://switzerland.iom.int/fr

ILO Country office - https://www.ilo.org/switzerland

NGO & Research Institutions

Caritas Swiss - https://www.caritas.ch/en/

Children Rights - https://www.humanium.org/en/

Save The Children - https://savethechildren.ch/de/

Swiss Refugee Council - https://www.refugeecouncil.ch/

Asylex - https://www.asylex.ch/