Following his visit to Mauritania between 2 – 12 September, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants has released his preliminary findings and recommendations concerning the country’s treatment of non-nationals. In advance of the mission, the Global Detention Project provided the Special Rapporteur with a detailed briefing documenting persistent violations of migrants’ and refugees’ rights, including arbitrary arrest and detention, inhumane detention conditions, and collective expulsions. Many of these concerns were echoed in his initial observations. […]

Mauritania: Mass Arrests and Deportations as EU Continues Efforts to Create “Bulwark” Against Irregular Migration

Under renewed pressure from the EU to prevent migrants from reaching the Canary Islands, in recent months Mauritanian authorities have arbitrarily arrested, detained, and expelled thousands of migrants. The West African state has come under repeated scrutiny in recent years for its detention and deportation practices, but the scale of the recent crackdown has attracted […]

Mauritania: Covid-19 and Detention

The IOM Mauritania office has informed the GDP that Mauritanian authorities have “informally” placed a moratorium on new detention orders during the crisis; police forces in both Nouakchott and Nouadhibou have reported that they were not detaining migrants. With borders closed and inter-regional movement restrictions in place, deportations from the country have also ceased. Reportedly, […]

Mauritania: Covid-19 and Detention

With the support of Frontex, an agreement between Spain and Mauritania allows for the return of Mauritanian nationals or migrants arriving in the Canary Islands. In 2018, four flights were carried out. However, from mid 2019 to mid March 2020, nine flights took place. According to the Mixed Migration Centre, at the beginning of the […]

Last updated: February 2010

Mauritania Immigration Detention Profile

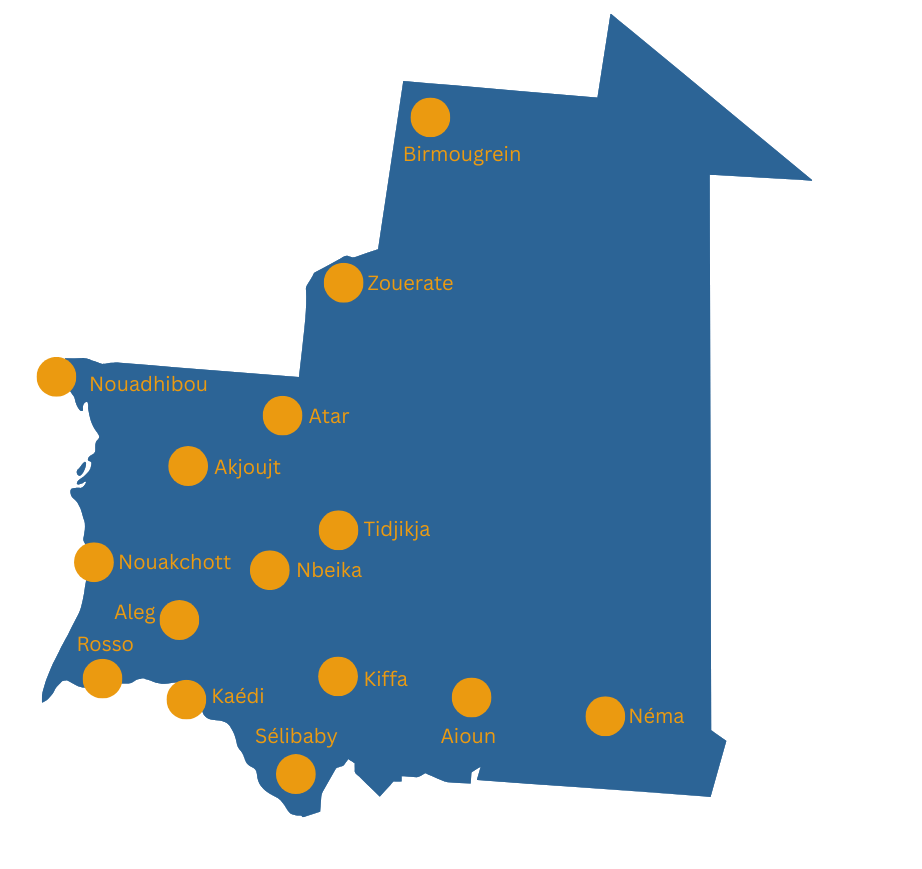

Mauritania has become a favoured transit point for African migrants attempting to reach Europe. The introduction of stricter border controls in Morocco and the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in the mid-2000s forced migrants to search out new routes, which resulted in the Mauritanian port city of Nouadhibou, located 800 km southeast of Spain’s Canary Islands, becoming a key departure hub (Amnesty 2008a; Choplin and Lombard 2007; Flynn 2006). Thousands of irregular migrants enter the country yearly, particularly from Senegal and Mali, to set out on perilous trips to the Canaries. Mauritania has established agreements with Spain on implementing stricter controls, including police checkpoints along its borders and surveillance operations to interdict smuggling vessels (USCRI 2009; Amnesty 2008a). In addition, Mauritania operates one dedicated immigration detention centre in Nouadhibou, nicknamed “Guantanamito” by detainees, which has been sharply criticised for its poor conditions (see USCRI 2009; Amnesty 2008a; CEAR 2008; WGAD 2008; Reuters 2006).

Detention Policy

The Decree 64.169 of 1964 (often referred to as the Aliens Acts) and the 1965 Decree 65.046 contain Mauritania’s key immigration norms. However, changes in immigration patterns over the past decade, as well as the introduction of new interdiction practices in response to pressure from Europe, have rendered certain aspects of Mauritanian law obsolete. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) reported in 2008 that the Aliens Act was undergoing revisions “as it is no longer adapted to the problems currently posed by migration in Mauritania. It does not criminalise attempts to leave the country illegally, which is often the reason given by the authorities for arresting foreigners heading for Europe. Such people are thus arrested and detained without any legal grounds” (WGAD 2008, p. 17; see also, Amnesty 2008a, p. 17).

The only reference to the departure of aliens in Mauritanian law is contained in the Aliens Act, which provides that foreign nationals who wish to leave the country must present identification documents to the authorities at exit points (CEAR 2008, p. 11). However, according to Mauritanian authorities, the police are authorized to apprehend people caught attempting to embark clandestinely by sea (WGAD 2008, p. 17).

Decree 65.046 of 1965 provides penalties for violating immigration norms. Article 1 provides for a fine of between 10,000-300,000 francs and 2-6 months imprisonment for, inter alia, entering or remaining in Mauritania in violation of immigration law. Articles 2 and 3 provide for up to one year imprisonment for using or providing false identity documents.

Many current immigration and detention practices are established in a 2005 government decree on refugees as well as in two agreements signed with Spain during the past decade.

Under the 2005 decree, which incorporated refugee rights into domestic law and established asylum application procedures, Mauritania can only expel refugees for security reasons. In addition, the decree states that refugees are allowed to travel abroad with travel permits (USCRI 2009).

Migrants have alleged numerous violations during detention procedures, including being arrested for not paying bribes to police officers; having residence permits torn up at the time of arrest; and being arbitrarily accused of attempting illicit travel to Europe (Amnesty 2008a, pp. 19-21).

The Agreement on Immigration signed by Mauritania and Spain in July 2003 provides the legal basis for cooperation between the two countries. Under the agreement, Spain can request that Mauritania readmit not only Mauritanian migrants but also migrants from third countries. According to Article IX of the agreement, Mauritania agrees to accept nationals from third countries who have not fulfilled immigration requirements and are “presumed” to have transited Mauritania en route to Spain.

In March 2006, Mauritania signed an additional agreement with Spain to conduct joint surveillance operations along the Mauritanian coast (Amnesty 2008a, p. 30). As part of the agreement, Spain sent four naval boats, a helicopter, and 20 specially trained civil guards (guardia civil) to help the Mauritanian authorities patrol the coast and conduct interdiction operations at sea (USCRI 2009; Reuters 2006). These efforts along the coast are in addition to the 63 police checkpoints and 37 gendarmerie checkpoints that Mauritania has set up along its borders with Mali and Senegal. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) has provided support to open five more checkpoints (USCRI 2009; Reuters 2006).

There are also legal complications with running the country’s single detention centre in Nouadhibou. Mauritania’s National Security Service (NSS) officially manages the centre, though there are no legal provisions authorizing this (Amnesty 2008a, p. 24). In addition, because of the lack of a clear framework for operating the centre, “there is no limit on the duration of detention, which may extend from one or two days to a week or more, until the police are able to organize transport for these people” (Amnesty 2008a, p. 24).

Services at the centre are provided by non-governmental organisations. The Mauritanian Red Crescent and the Spanish Red Cross fund and deliver meals to detainees, and provide them the opportunity to phone home. The Red Crescent also provides medical care. According to the Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid (CEAR), “The centre has a small and very basic clinic for first aid, and, if a migrant needs to be hospitalised, the Red Crescent accompanies them and pays their expenses, as there is no provision for medical coverage in th[e] country” (ESW 2009; Amnesty 2008a, p. 23).

In 2007, Mauritanian authorities detained 3,257 migrants, all of whom were subsequently expelled to either Senegal or Mali. According to Amnesty, “these people are left at the border, often without much food and with no means of transport” (Amnesty 2008b).

Detention Infrastructure

Mauritania has one dedicated detention centre for irregular migrants, in the port city of Nouadhibou. Opened in April 2006 in cooperation with the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), the centre formed part of Mauritania’s efforts to crack down on the number of migrants attempting to use Nouadhibou as a transit point for reaching the Canary Islands (ESW 2009; Amnesty 2008a, p. 21). The detention centre, which the Global Detention Project codes as an ad hoc facility because it operates without any apparent legal mandate, is located in a former school restored by Spanish authorities; classrooms have been fitted with bunk beds and transformed into detention cells. As of 2007, the facility was unmarked and surrounded by a one-metre high wall (Amnesty 2008a, p. 21; VOA News 2007). Before 2006, migrants arrested by the police were mostly held at a police station in Nouadhibou (Amnesty 2008a, p. 23).

Spain’s involvement in establishing the detention centre has raised questions over which authority controls the facility. While the centre is officially managed by the Mauritanian National Security Service (NSS), it is not governed by any regulations applicable to detention centres in the country (Amnesty 2008a, p. 24). Rather, as stated by Mauritanian officials “clearly and emphatically” to a delegation from CEAR in October 2008, Mauritanian authorities perform their jobs at the express request of the Spanish government (ESW 2009).

Services at the centre are provided by non-governmental organisations. The Mauritanian Red Crescent and the Spanish Red Cross fund and deliver meals to detainees, and provide them the opportunity to phone home. The Red Crescent also provides medical care. According to CEAR, “The centre has a small and very basic clinic for first aid, and, if a migrant needs to be hospitalised, the Red Crescent accompanies them and pays their expenses, as there is no provision for medical coverage in th[e] country” (ESW 2009; Amnesty 2008a, p. 23).

The NSS at Nouadhibou reported that in 2007 the centre detained 3,257 migrants, including 1,381 Senegalese and 1,229 Malians. It is estimated that 200-300 people are confined in the centre every month. Due to the lack of legal oversight of the centre, “there is no limit on the duration of detention, which may extend from one or two days to a week or more, until the police are able to organize transport for these people” (Amnesty 2008a, p. 24).

The high number of migrants taken in on a monthly basis has led to severe overcrowding, as noted by several groups who visited in 2008 (Amnesty 2008a; CEAR 2008; WGAD 2008). According to Amnesty, in March 2008 there were 216 bunk beds spread throughout the former classrooms, although only three rooms were being used during their visit. The organization reported that during its visit “a group of 35 who had been expelled by Morocco were being held in a room measuring 8m by 5m, with bars at the windows, which contained 17 bunk beds” (Amnesty 2008a, p. 21). Overcrowded cells have led to deplorable hygienic conditions, according to the Red Crescent (Reuters 2006).

Reports by human rights groups have also heavily criticised the treatment of detainees. Detainees have reported being beaten by police and locked up in cells day and night. They have also stated that they do not have access to showers, medical care, or interpreters, and that they have been forced to sign statements they do not understand (Amnesty 2008a, p. 11-12; WGAD 2008, p. 18-20). Overcrowding has led to minors being held in the same cells as adults, and has prevented the separation of criminals from immigration detainees (USCRI 2009).

In March 2008, both the regional director for national security and the Spanish Consul in Nouadhibou stated that plans were in place to construct a new detention centre that would conform to international standards (Amnesty 2008a, pp. 38-39). It is not clear, however, whether this has yet been undertaken. In previous years plans were made to build four additional detention centres—in Zouerate, Nouakchott, Rosso and Kaedi—but these plans were eventually scrapped (Reuters 2006).

Facts & Figures

The majority of migrants transiting Mauritania en route to the Canary Islands are from Senegal and Mali. Of the 3,257 detainees held at the Nouadhibou detention centre in 2007, 1,381 were Senegalese and 1,229 were Malian (Amnesty 2008a, p. 24).

While the number of migrants intercepted and expelled by Mauritanian and Spanish authorities has declined over the past four years, it still numbers in the thousands. In 2006, officials estimated that approximately 11,600 migrants were intercepted in the water or arrested by local police and taken to Mauritania’s border with either Mali or Senegal to be expelled. In 2007, this figure dropped to 7,100 intercepted and expelled, and fell further to 5,969 in 2008 (Frontex 2009; Amnesty 2008a, p. 25). The number of migrants reaching the shores of the Canary Islands by boat has also dropped significantly, from 31,678 in 2006 to only 9,181 in 2008. According to the Spanish Interior Ministry, 1,472 successfully made the crossing in the first four months of 2009 (ESW 2009; Frontex 2009).

Mauritania has a sizeable refugee population. According to UNHCR, as of January 2009, Mauritania was hosting a total of 27,041 refugees and people in refugee-like situations, of whom 642 had been assisted by UNHCR. There were also 62 pending cases for asylum (UNHCR 2009). During 2008, more than 1,000 new refugees and asylum seekers registered in Mauritania, the largest number coming from Sudan. Of these, 775 were issued documents by the government (USCRI 2009).The vast majority of refugees, some 26,000, are ethnic Sahrawis from the disputed Western Sahara held by Morocco; another 3,500 refugees are from Mali (USCRI 2009).

References

- Amnesty International (AI). 2008a. “Mauritania: Nobody Wants to Have Anything to Do With Us.” AFR 38/001/2008. 1 July 2008.http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/AFR38/001/2008/en/d05d42f1-393e-466c-831a-822d76fa3c1e/afr380012008eng.pdf (accessed 11 November 2009).

- Amnesty International (AI). 2008b. “Migrants face illegal arrest in Mauritania.” AI. 2 July 2008. http://www.amnestyusa.org/document.php?lang=e&id=ENGNAU200807025281 (accessed 29 January 2010).

- Choplin, Armelle and Jérôme Lombard. 2007. “Destination Nouadhibou pour les migrants africains.” Mappemonde: Numéro 88.http://mappemonde.mgm.fr/num16/lieux/lieux07401.html (accessed 18 November 2009).

- Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado (CEAR). 2009. “Informe de evaluación del centro de detención de migrantes en Nouadhibou (Mauritania).” CEAR. Declarada de Utilitad Pública. G 28651529. 2009.http://www.cear.es/files/Informe%20CEAR%20Nouadhibou%202009%20.pdf(accessed 11 November 2009).

- European Social Watch (ESW). 2009. “Spain: The Externalisation of Migration and Asylum Policies: The Nouadhibou Detention Centre.”http://www.socialwatch.eu/wcm/Spain.html (accessed 2 February 2010).

- Flynn, Michael. 2006. “Europe: On Its Borders, New Problems.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. November/December 2006.http://www.globaldetentionproject.org/fileadmin/publications/Flynn_Europe_Migration.pdf.

- Frontex. 2009. “HERA 2008 and NAUTILUS 2008 Statistics.” 17 February 2009. http://www.frontex.europa.eu/newsroom/news_releases/art40.html(accessed 18 November 2009).

- Jaaffar, Salim. 2005. “Les droits des étrangers en Mauritanie au regard des réfugiés et des demandeurs d’asile,” Revue du droit des étrangers en Mauritanie. Nouakchott, 18 March 2005.

- Ramdam, Haimoud Ould. “Droit des étrangers et protection des réfugiés en Mauritanie,” Mémorandum. Revue juridique de droit mauritanien. April 2007.

- Reuters. 2006. “Mauritania: Migrants Lie in Waiting.” Reuters. 2 November 2006.http://www.alertnet.org/thenews/newsdesk/IRIN/939977a148a66d1938848b4b26a8698c.htm (accessed 11 November 2009).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2009. “Mauritania.” Web site. http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e486026 (accessed 18 November 2009).

- United States Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI). 2009. “Mauritania.” USCRI. http://www.refugees.org/countryreports.aspx?id=2362(accessed 11 November 2009).

- VOA News. 2007. “Clandestine Migration Changes in Mauritanian Hub Town.” VOA News. 3 August 2007.http://www1.voanews.com/english/news/a-13-2007-08-03-voa32-66723207.html (accessed 11 November 2009).

- Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD). 2008. “Mission to Mauritania.” United Nations Human Rights Council. A/HRC/10/21/Add.2. 21 November 2008. http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G08/168/99/PDF/G0816899.pdf?OpenElement(accessed 11 November 2009).

DETENTION STATISTICS

DETAINEE DATA

DETENTION CAPACITY

ALTERNATIVES TO DETENTION

PRISON DATA

POPULATION DATA

LEGAL & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

Does the Country Have Specific Laws that Provide for Migration-Related Detention?

Do Migration Detainees Have Constitutional Guarantees?

Additional Legislation

GROUNDS FOR DETENTION

Immigration-Status-Related Grounds

Criminal Penalties for Immigration-Related Violations

Grounds for Criminal Immigration-Related Incarceration / Maximum Length of Incarceration

Has the Country Decriminalised Immigration-Related Violations?

LENGTH OF DETENTION

DETENTION INSTITUTIONS

Types of Detention Facilities Used in Practice

PROCEDURAL STANDARDS & SAFEGUARDS

Procedural Standards

COSTS & OUTSOURCING

COVID-19 DATA

TRANSPARENCY

MONITORING

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MONITORING BODIES

NATIONAL PREVENTIVE MECHANISMS (OPTIONAL PROTOCOL TO UN CONVENTION AGAINST TORTURE)

NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS (NGOS)

Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) that Carry Out Detention Monitoring Visits

GOVERNMENTAL MONITORING BODIES

INTERNATIONAL DETENTION MONITORING

INTERNATIONAL TREATIES & TREATY BODIES

International Treaties Ratified

Ratio of relevant international treaties ratified

Relevant Recommendations or Observations Issued by Treaty Bodies

40.The Committee urges the State party to take all necessary legislative and practical measures to rule out any refoulement or collective expulsion of migrants and to ensure that all allegations of such practices are duly investigated and that those responsible are prosecuted and, if found guilty, sanctioned. It also recommends that the State party actively work to strengthen mutual legal assistance in order to facilitate the exchange of information and evidence and the search for and identification of disappeared migrants. In implementing these recommendations, the Committee encourages the State party to take into account its general comment No. 1 (2023) on enforced disappearance in the context of migration.

and, if this becomes necessary, that they are held for as short a time as possible and that use is made of alternatives to detention whenever feasible.

(g) Continue to ensure that the National Human Rights Commission and other human rights organizations have unhindered access to all places of detention, which includes the ability to make unannounced visits and to hold private interviews with detainees.

(b) to refrain from detaining migrant workers for infringing migration laws other than in exceptional cases and as a last resort and to ensure that, in all cases, they are segregated from ordinary offenders and that women are segregated from men, and minors from adults."

"§41. (a) facilitate access to consular or diplomatic assistance for mauritanian migrant workers living abroad, especially in cases of detention or expulsion;

(b) ensure that its consular services more effectively fulfil their mission to protect and promote the rights of mauritanian migrant workers and members of their families and, in particular, that they provide the necessary assistance to those who are deprived of their liberty or under an expulsion order;

(c) take the necessary steps to ensure that the consular or diplomatic authorities of countries of origin, or of a country representing the interests of those countries, are systematically notified of the detention in the state party of one of their nationals and that the requisite information is duly entered in the police custody register (persons contacted, date, time, etc.);"

(a) Expedite the adoption of the draft National Asylum Law that has been pending since 2014, and ensure that it is fully in line with the Convention, in order to facilitate the access of asylum-seeking children to fair, efficient and child-sensitive asylum procedures and to local integration, including for such children in need of international protection;

(b) Ensure that all asylum-seeking, refugee and migrant children, regardless of their status, can obtain individual identity documentation and have access to formal education and medical care;

(c) Prohibit the detention of asylum-seeking, refugee and migrant children and provide alternatives that allow children to remain with their family members and/or guardians in non-custodial, community-based contexts;

(d) Take all necessary measures to prevent the recruitment of Malian refugee children by non-State armed groups."

Global Detention Project and Partner Submissions to Treaty Bodies

§ 35. The Committee recommends that the State party:

(a) Indicate in its next periodic report the number of migrants, disaggregated by age, sex and nationality and/or origin, who are currently in detention for infringing migration laws, specifying the location, average duration and conditions of their detention and providing information on the decisions rendered in their regard and on the steps taken to ensure that an alternative to detention is provided;

(b) To refrain from detaining migrant workers for infringing migration laws other than in exceptional cases and as a last resort and to ensure that, in all cases, they are segregated from ordinary offenders and that women are segregated from men,

and minors from adults.

§ 15. Please provide information on the detention centres in which migrant workers are placed, and on the conditions of detention, and state

(a) whether persons detained for immigration-related reasons are systematically separated from ordinary detainees;

(b) whether women are separated from men; and

(c) whether women detainees are supervised by female guards.

> UN Special Procedures

Relevant Recommendations or Observations by UN Special Procedures

refugee protection.

b) End collective expulsions and ensure every individual case is assessed before

removal. Revise Article 3 of Law No. 2024-029 to incorporate procedural

safeguards in line with Mauritania’s human rights obligations and the principle of

non-refoulement.

c) Ensure the protection of family unity and the best interests of the child by

implementing protocols that prevent family separation during deportation and

disembarkation, including prior family assessments, prioritization of non-custodial

measures for families with children, and coordination with child protection services

for reunification and care of unaccompanied or separated minors.

...

f) Strengthen judicial oversight of detention and guarantee humane conditions in all

centres.

g) Establish independent bodies to investigate and sanction corruption and abuse

against migrants, asylum seekers and refugees by police officers

h) Improve security forces' training in human rights, ensuring the protection of the

human rights of migrants during checks and interventions.

i) Provide gender-sensitive protections, including shelters for women and children.

...

l) Allocate domestic resources to search-and-rescue operations and migrant reception

facilities.

m) Ensure that any return measure concerning a migrant is based on an individual

procedure, respectful of fundamental rights and in compliance with the principle of

non-refoulement and international standards.

n) Facilitate access to legal status for migrants in Mauritania by reducing

administrative, financial, and legal barriers to obtaining and renewing residence

permits.

o) Ensure that administrative detention centres comply with international human rights

standards, by providing dignified, humane, and secure conditions of detention for

migrants deprived of liberty.

p) Train security forces on the rights of migrants and the fight against trafficking, in

order to prevent human rights violations in the context of migration management

and to strengthen the capacity of security personnel to protect migrants, especially

those exposed to trafficking and smuggling.

q) Raise awareness of existing complaint mechanisms and ensure that migrants have

secure, confidential, and impartial access to a complaint mechanism in case of rights

violations, outside of administrative or security structures involved in their control.

Global Detention Project and Partner Submissions to UN Special Procedures

> UN Universal Periodic Review

Relevant Recommendations or Observations from the UN Universal Periodic Review

REGIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MECHANISMS

Regional Legal Instruments

HEALTH CARE PROVISION

HEALTH IMPACTS

COVID-19

Country Updates

Last updated: February 2010

Government Agencies

Ministre de l'Intérieur et de la Décentralisation http://www.interieur.gov.mr/

International Organizations

International Labour Organisation - Le Bureau Sous Régional de l'OIT pour le Sahel (French), https://www.ilo.org/fr/bureau-de-loit-%C3%A0-dakar

International Organisation for Migration – Mauritania Country Information, https://www.iom.int/countries/mauritania

UN High Commissioner for Refugees – Mauritania Country Information, https://www.unhcr.org/where-we-work/countries/mauritania

NGOs and Research Institutions

Amnesty International – Mauritania, https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/africa/west-and-central-africa/mauritania/

Human Rights Watch – Mauritania https://www.hrw.org/middle-east/north-africa/mauritania

Mauritanian Red Crescent https://www.ifrc.org/national-societies-directory/mauritanian-red-crescent