The Global Detention Project (GDP) welcomes the opportunity to provide input ahead of the Special Rapporteur’s preparation of his second report on the externalisation of migration governance and its impact on migrants. This submission draws on our monitoring and documentation of detention practices as part of externalisation schemes, highlighting the ongoing rights violations committed against migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers forcibly removed to third countries.

Our report also draws attention to the compelling connection between externalisation and the spread of arbitrary immigration detention practices across the globe. The decades-long efforts of wealthy states to export migration control practices to countries in the Global South have led to the emergence of new immigration detention regimes in countries that lack basic oversight mechanisms, legal grounds for detention, transparency, or the basic rule of law, resulting in a growing population of detained migrants and refugees vulnerable to extreme human rights abuses with little or no recourse to remedies or justice.

1. RECENT TRENDS: HEAVY RELIANCE UPON DETENTION

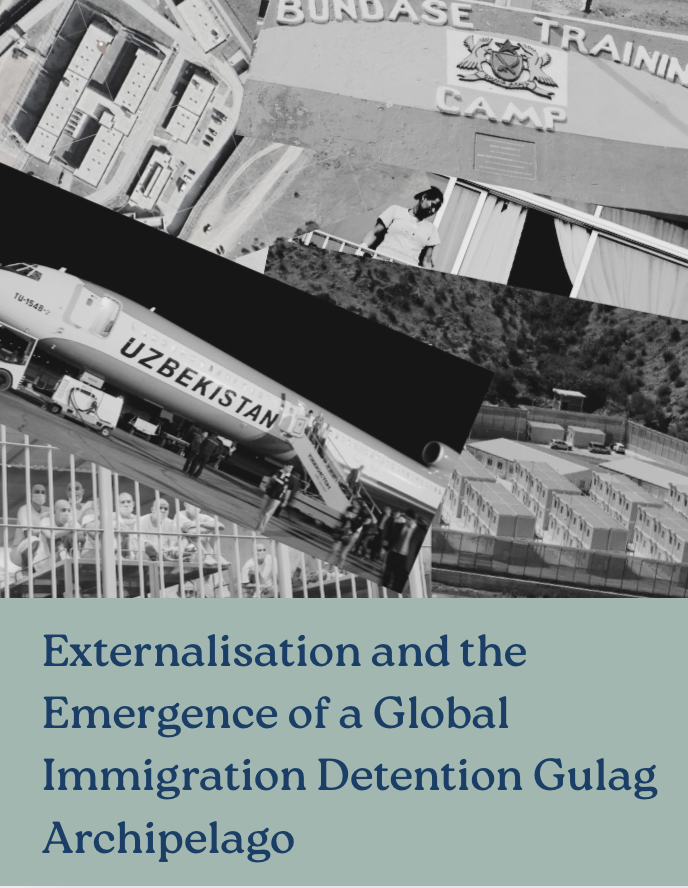

Since Spring 2025, the Global Detention Project has carefully documented the growing number of bilateral agreements facilitating the externalisation of migrant and asylum management–many of which involve the United States. These include agreements with countries including Kosovo, Ghana, Uganda, Eswatini, South Sudan, and most recently, Equatorial Guinea. According to Human Rights First, who house the ICE Flight Monitor, as of October the Trump administration had carried out at least 21 flights carrying third country nationals to ten countries (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Eswatini, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Rwanda, South Sudan, and Uzbekistan). Third country transfers have also been conducted over the border to Mexico. Generally, these transfers have occurred with short or no notice, with deportees denied any opportunity to contest their removal from the United States. Documentation also reveals that they have involved abusive treatment and violence, with deportees frequently shackled for large parts of the journey.

For receiving states, these agreements appear to be less about humanitarian responsibility, and more about serving political, economic, and geo-strategic objectives. This was emphasised to the GDP by an observer in Kosovo, who–discussing Kosovo’s rationale for agreeing to accept deportees from the U.S and the U.K–noted that: “When it comes to Kosovo, it’s a young country that needs support for its claims of independence, as well as financial support for sectors like security.”

In Uganda, which signed an agreement with the United States in July 2025, domestic critics argue that President Museveni is using the deal to ease international pressure on his government–which faces accusations of persistent corruption and weakening commitment to democracy. Media outlets, meanwhile, confirm that Eswatini received 5.1 million USD from the United States to receive deportees, and reports suggest authorities in the country may be using the deal to curry favour in the U.S to negotiate better trade terms.

Yet, regardless of the reasoning for agreements, one thing is clear: far from safeguarding migrants’, refugees’, and asylum seekers’ rights, these (often opaque, and largely performative) arrangements continue to lead to serious rights violations, and are disappearing people without due process. As one refugee-protection expert stated in an interview with the New Yorker, the specific face of deportees often remains “a total black hole.”

In many cases, agreements–seemingly concluded with minimal or no legal safeguards or oversight–facilitate the transfer of migrants to countries with minimal reception infrastructure and weak legal protections. Commonly, detention has featured at the centre of these arrangements, with deportees subjected to arbitrary and abusive detention with inadequate access to basic rights–as well as, in some cases, forced removal and refoulement.

In several cases, such as the 30 April removal of Kyrgyz and Kazakh nationals to Uzbekistan, little information is known about the deportees themselves, leaving observers with serious concerns regarding what protection claims they may have had in the U.S, and whether their inclusion in such schemes has led to their refoulement to a country where they face serious risk of abuse.