Since the Pahalgam terrorist attacks in Kashmir in April, anti-Islamic public and official attitudes across India have led to important ethnic groups in the country–including Rohingya and Bengali-speaking Muslims–being targeted for racial violence and increasing detention and deportation operations. According to reports, more than 2,500 Bangladeshi nationals have been detained and forcibly deported since May. The resurgence in Hindu nationalist-driven racial violence follows years of efforts by the government to present non-Hindus as internal security threats.

Renewed Anti-Muslim Sentiment

On 22 April, 26 people were killed in a terrorist attack in Pahalgam (Jammu-Kashmir) carried out by Pakistan-based militants affiliated with Lashkar-e-Taiba. It is considered the deadliest terrorist attack targeting Indian civilians since the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks. Since then, the country has witnessed renewed anti-Muslim sentiment and intimidation, with the India Hate Lab documenting at least 64 anti-Muslim hate speech events in nine states and the region of Jammu-Kashmir in the ten days after the attack. The NGO report identifies far-right events in which speakers referred to Muslims as “green snakes,” “piglets,” and “mad dogs,” and often called for violence and threatened to expel Muslims from localities. Members of the country’s ruling (Hindu-Nationalist) BJP party have been apprehended by police for abusing and assaulting Muslim hawkers in central Mumbai.

Alongside this has been a renewed effort by authorities to remove “illegal foreigners” from the country–a practice that the BJP-led government has heavily pursued since coming into power in 2014 (see, for example, our our 2023 blog on the detention of Rohingya refugees in Uttar Pradesh, and our 2024 Urgent Appeal on the situation of Myanmarese refugees in India.).

Following Operation Sindoor–India’s military response to the terrorist attack, launched on 7 May, which included strikes on sites in Pakistan and Pakistani Kashmir–the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) ordered states to apprehend and remove “illegal foreigners” from the country.

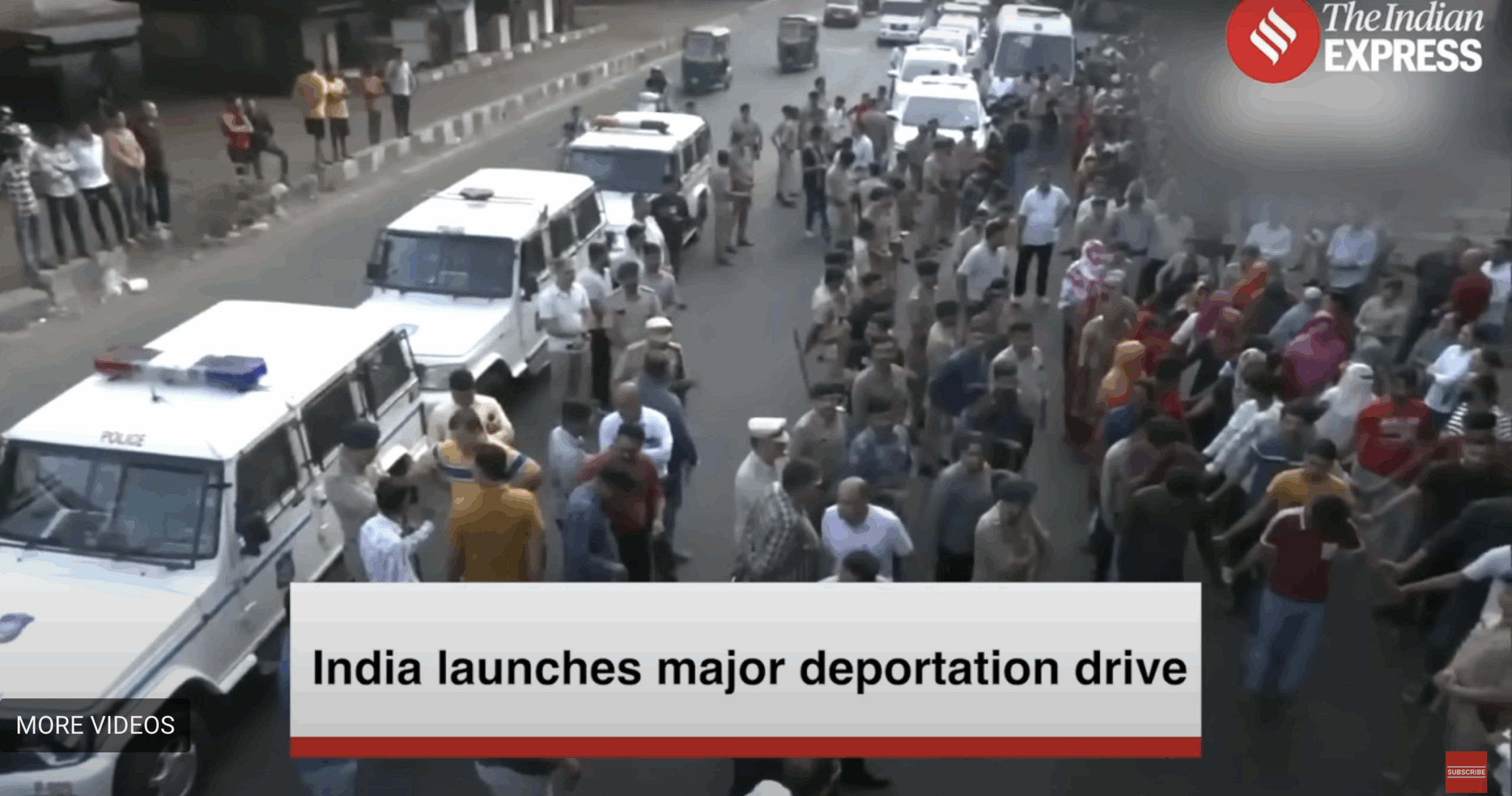

According to The Indian Express, in May the MHA introduced a 30-day deadline for states and Union Territories to verify the citizenship status of “suspected” undocumented immigrants from Bangladesh and Myanmar. If citizenship cannot be confirmed within 30 days, states are to detain and deport such individuals (with the MHA directing them to set up sufficient detention centres at the district level). The newspaper adds that in states like Gujarat, Delhi, Assam, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan, “identified illegal immigrants” have been rounded up and detained; transported in Air Force aircraft to border points in Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya; and pushed across the border into Muslim-majority Bangladesh by Border Security Forces. Since 7 May, it writes, more than 2,500 people have been removed in this way.

Pushbacks at Gunpoint – Abandoned at Sea

Testimonies shared by media outlets including the BBC and the Associated Press depict brutal treatment during these removals, and a total disregard for due process.

In an account shared by the BBC, one woman describes being called into a police station before immediately being pushed across the border at gunpoint. Here, she says, she was left stranded in the no-man’s land between India and Bangladesh for two days “without food or water in the middle of a field in knee-deep water teeming with mosquitoes and leeches.” This woman, the BBC reports, was later returned to India–along with several others who actually possessed necessary documents to reside in India. Other accounts have highlighted the alarmingly swift and secretive manner in which these removals have taken place.

As well as pushing people over the border into Bangladesh, Indian authorities have also detained Rohingya refugees living in Delhi before casting them into the sea near the maritime border with Myanmar. In May, numerous reports highlighted the Indian government’s actions: approximately 40 refugees were detained in Delhi before being blindfolded, flown to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and transferred to an Indian naval ship. After crossing the Andaman Sea, the group were reportedly given life jackets before being forced into the sea and ordered to swim to an island in Myanmar’s territory.

Tom Andrews, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, expressed grave concerns at these reports. In a statement, he said: “The idea that Rohingya refugees have been cast into the sea from naval vessels is nothing short of outrageous. I am seeking further information and testimony regarding these developments and implore the Indian government to provide a full accounting of what happened. … Such cruel actions would be an affront to human decency and represent a serious violation of the principle of non-refoulment.”

Earlier, in March, the Special Rapporteur sent a communication to the Indian government in which he highlighted his concerns regarding the “widespread, arbitrary and indefinite detention of refugees and asylum seekers from Myanmar,” as well as the “inadequate conditions, ill-treatment, and deaths in custody of Rohingya refugees in detention centers.”

In a joint urgent appeal to the Special Rapporteur last year, the GDP, the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network, and civil society partners in India urged him to address the ill treatment of Myanmar refugees India. Mr Andrews’s March 2025 letter to the Indian government echoes many of the recommendations in our urgent appeal, including repeating our call for India to immediately cease the arbitrary detention of Myanmar refugees and improving access to detention centres by independent monitors.

Immigration Detention in India

India’s legal framework does not distinguish between refugees and undocumented immigrants and thus treats anyone without valid travel documentation as an illegal immigrant liable to arrest, detention, and deportation (sections 3 and 14 of the Foreigners Act of 1946, and the Passports Act of 1967). As per a 1958 directive of the Union Government, the powers to arrest, detain, and deport under the Foreigners Act are vested in States and Union Territories, meaning that these governments can exercise the power to detain and deport foreign nationals.

Immigration detention lacks a specific time limit, meaning that it can continue for exceedingly long periods. Conditions can often be dire. As the Special Rapporteur noted in his 2025 communication, echoing many of the GDP’s points: “Detainees from Myanmar, the majority of whom are Rohingya, are reportedly held in severely overcrowded cells, and do not receive adequate nutrition, clean water, or medical care. Facilities are reportedly unsanitary. Detainees lack clean clothes, bedding, and access to sunlight. Many detainees are reportedly suffering from illness, infections and other medical problems and are unable to access adequate medical care. There is reportedly no adequate oversight of places of detention by independent actors, including UNHCR.”

Nowhere is the issue of detention as fraught as in the state of Assam, where millions of people are disenfranchised because of the state’s racially charged ‘National Register of Citizens’ (NRC). Published in 2019, this is a register of people who can prove they came to Assam before 24 march 1971 and which excludes nearly 2 million Assam residents. Those who are excluded are vulnerable to being labelled “illegal” by so-called “foreigners’ tribunals,” leaving them at risk of detention. According to the BBC, affected persons can only file an appeal regarding their exclusion from the register once there is a gazette notification (in other words, once it is authorised as a legal government document), which has not yet been issued.