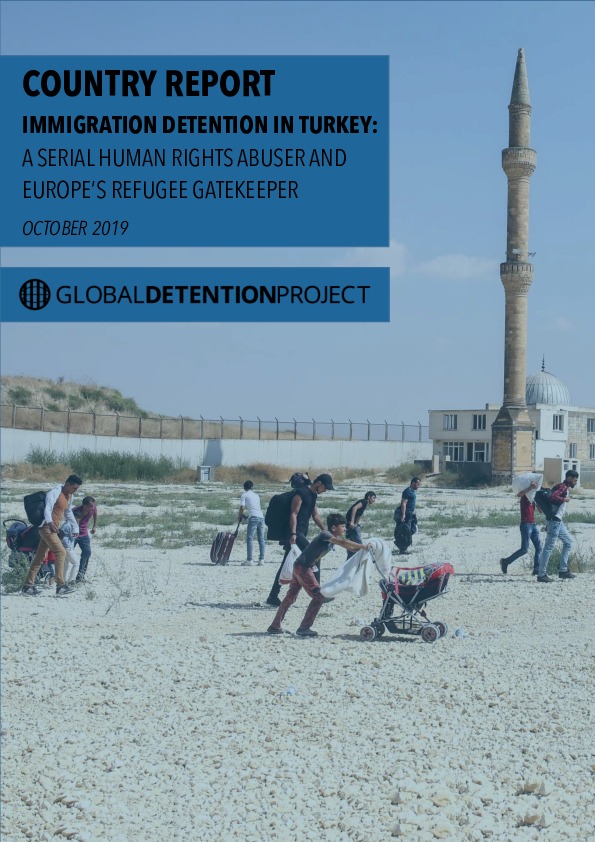

Immigration Detention in Turkey (2019 Report): Turkey has long served as Europe’s reluctant and opportunistic gatekeeper for refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants from across the Near East and Asia. This role was dramatically put on display in the wake of the refugee “crisis” in 2015 and remains an important flashpoint in the country’s relations with the European Union, a fact that was underscored by Turkish officials in the wake of the country’s military incursions into Kurdish-controlled areas of Syria in late 2019. The 2016 EU-Turkey refugee deal was the culmination of years of EU efforts to encourage and finance Turkey’s migration control efforts, including by boosting its detention capacity. Read the Turkey Immigration Detention Profile.

Introduction to the 2019 Report

Turkey has one of the world’s largest immigration detention systems, which is comprised of some two dozen “removal centres” as well as ad hoc detention sites along its borders, transit facilities in airports, and police stations. Located between Europe and Asia, Turkey’s policies are the result of numerous factors related to its geography, history, and politics. Its relationship with the European Union (EU) has been particularly crucial because of its location as a buffer between the EU and the Middle East and its role as de facto—and often opportunistic—gatekeeper for millions of refugees seeking safe haven in Europe.

In 2015, with the onset of the “refugee crisis,” more than a million people made their way to Europe. Some 80 percent of these people crossed Turkey. In response, Brussels negotiated an agreement with Ankara aimed at stemming refugee flows. The 2016 EU-Turkey deal established that all migrants and asylum seekers who arrived on Greek islands after 20 March 2016 would be liable to return to Turkey. For every migrant or asylum seeker returned to Turkey, the EU would resettle one Syrian from Turkey. Turkey was also promised six billion EUR, the lifting of EU visa requirements for its nationals, and the resumption of Turkey’s EU accession process. While the EU justified the return of migrants and asylum seekers to Turkey on the “safe third country” principle, it was patently clear that Turkey would not fulfil the criteria to be considered safe for refugees.

After the failed 2016 coup against the government of President Recep Tayip Erdogan, Turkey issued an emergency decree—Presidential Decree No. 676—that gave authorities broad powers vis-à-vis the detention and deportation of non-citizens. The government also initiated a harsh crackdown on many sectors of Turkish society. In the ensuing months, 130,000 civil servants were dismissed from their jobs, some 80,000 people were detained, and thousands of NGOs were shut down for alleged terrorism-related reasons.

Since the events of 2015 and 2016, Turkey’s immigration system has been under intense pressure, compounded by the large-scale dismissals of public servants, which strained the “bureaucratic capacity in areas ranging from the judiciary to law enforcement and education, all of which are relevant to refugee absorption capacity.” The government has responded to these pressures with a series of draconian measures, leading to widescale human rights violations.

In October 2016, the government issued an emergency decree that enumerated conditions in which officials could ignore non-refoulement obligations, many of which were later made into law. Since the decree, Turkey has increased deportations of refugees and asylum seekers to unsafe countries, including Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq. Most recently, in July 2019, authorities in Istanbul announced raids, stop-checks, and arrests of Syrian refugees registered in other cities. The raids were followed by summary deportations into northern Syria.

Turkey has sought to counter criticsm of its treatment of Syrians by arguing that more than 315,000 people have returned to Syria at their own free will in recent years. However, observers argue that many of these departures are far from voluntary. For instance, in a widely noted 2019 report, Amnesty International related the accounts of Syrian deportees who were beaten and threatened with violence in order to coerce them into signing “voluntary return” documents.

Such expulsions have taken place against the backdrop of Turkey’s desire to establish a “safe zone” along its border with Syria, a plan that the Erdogan administration rapidly sought to achieve following U.S. President Donald Turmp’s military pullback in Syria and Turkey’s ensuing military offensive against Kurdish forces in late 2019. They have also been fueled by surging anti-foreigner rhetoric, particularly aimed at Syrians, which has featured heavily in political campaigns and been accompanied by attacks on Syrian refugees and Syrian-owned properties.

Turkey has historically served as a crucial transit area for refugees and migrants, dating back long before the current turmoil in the region. Since the outbreak of the Syrian conflict, the country has hosted some 3.5 million Syrian refugees. With Turkey also hosting refugee populations from Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries, the total number of refugees and asylum seekers in Turkey is close to four million. Given the country’s importance to regional migration, the EU has repeatedly sought to partner with it on control initiatives, including a 2013 EU-Turkey readmission agreement that obliged Turkey to readmit its own citizens as well as “third-country nationals” who enter the EU directly from Turkey.

Since the EU-Turkey Action Plan on Migration, the EU-Turkey deal, and the July 2016 coup attempt, the country has continued to bolster its detention infrastructure. In particular, the EU-Turkey deal paved the way for the establishment of new facilities for detaining non-nationals, particularly those returned from Greece. In 2018, six EU-funded facilities originally intended as reception centres for asylum seekers were transformed into removal centres, doubling the country’s official detention capacity. As of mid-2019, Turkey reportedly was operating 24 removal centres, with several others either under renovation or construction.