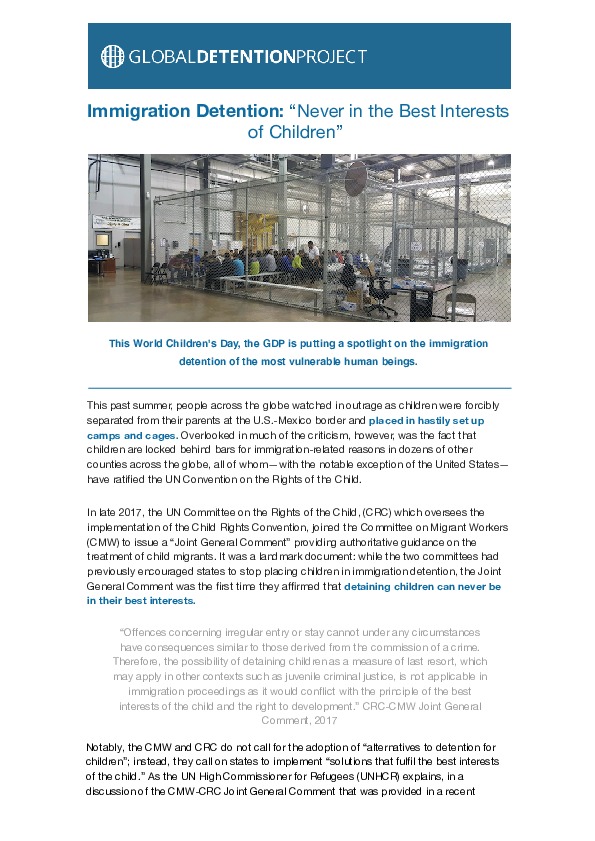

This World Children’s Day, the GDP is putting a spotlight on the immigration detention of the most vulnerable human beings.

This past summer, people across the globe watched in outrage as children were forcibly separated from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border and placed in hastily set up camps and cages. Overlooked in much of the criticism, however, was the fact that children are locked behind bars for immigration-related reasons in dozens of other counties across the globe, all of whom—with the notable exception of the United States—have ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

In late 2017, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, (CRC) which oversees the implementation of the Child Rights Convention, joined the Committee on Migrant Workers (CMW) to issue a “Joint General Comment” providing authoritative guidance on the treatment of child migrants. It was a landmark document: while the two committees had previously encouraged states to stop placing children in immigration detention, the Joint General Comment was the first time they affirmed that detaining children can never be in their best interests.

“Offences concerning irregular entry or stay cannot under any circumstances have consequences similar to those derived from the commission of a crime. Therefore, the possibility of detaining children as a measure of last resort, which may apply in other contexts such as juvenile criminal justice, is not applicable in immigration proceedings as it would conflict with the principle of the best interests of the child and the right to development.” CRC-CMW Joint General Comment, 2017

Notably, the CMW and CRC do not call for the adoption of “alternatives to detention for children”; instead, they call on states to implement “solutions that fulfil the best interests of the child.” As the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) explains, in a discussion of the CMW-CRC Joint General Comment that was provided in a recent UNHCR “alternatives to detention” assessment guide, “It is improper to refer to [child] reception measures as alternatives to detention for children, because children should not be detained for immigration related purposes. Children should always be referred to appropriate care arrangements as their deprivation of liberty would be contrary to international law.”

The contradiction between calling for ending the detention of children and the adoption of “alternatives to detention” for children has been highlighted by a growing number of observers, including the GDP’s executive director.

Notwithstanding the strengthening of the norm against child immigration detention, numerous recent GDP reports—including on Libya and Egypt—reveal that children around the world continue to be detained, often in environments that leave them extremely vulnerable to abuse and neglect.

In some countries, the law is ambiguous or misleading when it comes to the detention of children. In Canada, for instance, children are “housed” as “guests” of their parents in immigration detention; in France, Poland, and Spain children “accompany” their parents in detention centres. Such policies can make detained children “invisible” to the law, preventing them from accessing important procedural safeguards offered other detainees. In Bulgaria and the French overseas territory of Mayotte, where unaccompanied minors cannot be detained, reports indicate that such children are often falsely linked to unrelated adults in order to classify them as “accompanied,” paving the way for their detention and expulsion.

“When children are accompanied, the need to keep the family together is not a valid reason to justify the deprivation of liberty of a child. When the child’s best interests require keeping the family together, the imperative requirement not to deprive the child of liberty extends to the child’s parents and requires the authorities to choose non-custodial solutions for the entire family.” CRC-CMW Joint General Comment, 2017

The GDP has repeatedly highlighted child detention practices in reports, including in our submissions to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. But so much more has to be done to make sure this practice receives the scrutiny it deserves. This World Children’s Day, please join us on Twitter (@migradetention) and help us to shine a spotlight on the treatment of child migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees around the world.