As of mid-February, the Trump administration has quietly deported seventeen men and women to Cameroon under a murky arrangement that is part of broader U.S. efforts to send “unremovable” migrants and asylum seekers to third countries. Upon arrival in the capital Yaoundé, the deportees were reportedly detained and threatened with removal to their countries of origin. This is the latest in a series of third-country deportation schemes pushed by the Trump administration since taking office in 2024, which a recent report by the U.S Senate Foreign Affairs Committee criticised for excessive costs, lack of accountability and oversight, and engagement with corrupt and unstable foreign governments.

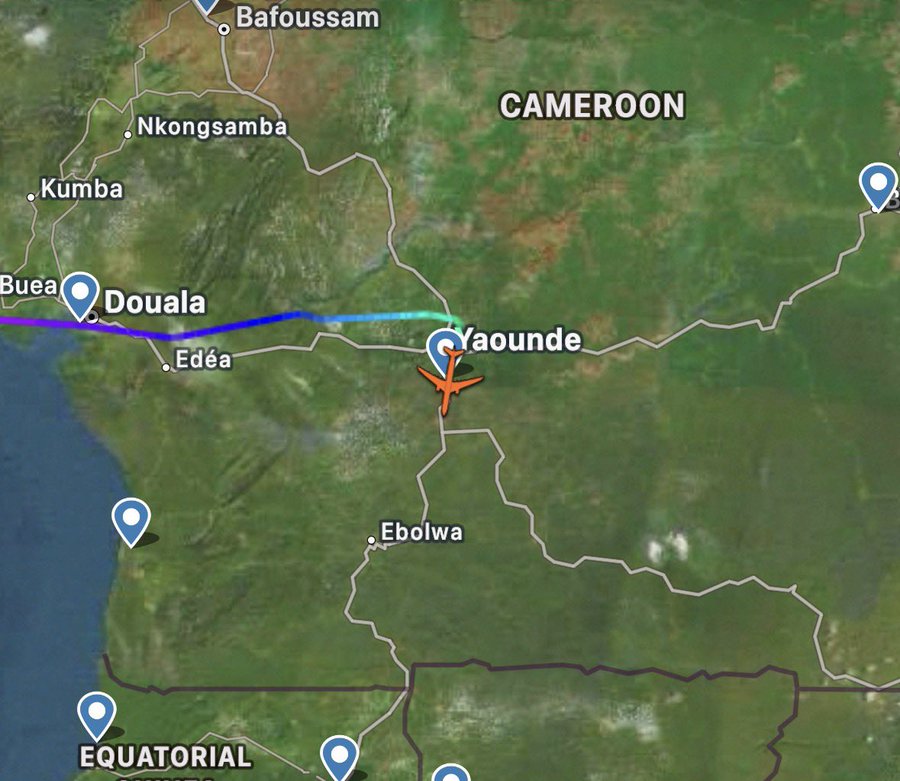

The New York Times and Associated Press reported that two groups of third-country nationals have been deported from the United States to Cameroon, one on 14 January and another on 15 February. According to the New York Times, which spoke with deportees from the first group, most of the deportees had been granted legal protections from being sent back to their home countries (Angola, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Morocco, and Zimbabwe). There are currently no details regarding those deported on 15 February, but according to ICE Flight Monitor, the second group arrived in Cameroon on flight OAE4060 from Louisiana, after a brief stop in Dakar, Senegal. The plane subsequently landed in both Ghana and Chad.

The deportees told the New York Times that they did not know they were being sent to Cameroon “until they were handcuffed and chained on a Department of Homeland Security Flight leaving Alexandria, LA, on Jan.14.” Similar allegations have been documented in other third country removals from the United States, including during the transfer of third country nationals to Ghana in September.

Detention Shrouded in Secrecy

Upon arrival, the first group of men and women were detained in a“state-owned compound in Yaoundé,” according to the Times, which published an image showing at least five bunk beds crammed together in a room. According to observers with whom the Global Detention Project has been in email correspondence, the detention compound is opposite the Presbyterian Church Adna, in Yaoundé. Cameroonian authorities appear to be attempting to shield the detention operations here from scrutiny: on 17 February, four journalists and a lawyer representing the detainees were arrested outside the compound. Media reports allege that at least one of the journalists was beaten, and that prior to their eventual release, journalists’ phones, cameras, and laptops were confiscated by the police.

Speaking to the New York Times, Joseph Awah Fru, the lawyer assisting the detainees, said: “The state cannot prevent the public from knowing where they are keeping deportees who are not even citizens. That goes to the whole idea of shady deals in the dark.”

Cameroon does not operate dedicated immigration detention facilities and its legislation does not appear to provide for administrative immigration-related detention. Instead, the country’s Law No. 1997/012 of 10 January 1997 criminalises the irregular entry, stay, and exit of foreigners (Article 40).

According to several detainees and their lawyers, they were informed that they could not leave the facility unless they agreed to return to their home countries–which most had originally fled to escape war or persecution. The deportees also claimed that there was no support for them to apply for asylum in Cameroon (although the IOM claimed that it had referred them all to UNHCR to request asylum). As of 16 February, the Cameroonian government has not commented publicly on the arrival or whereabouts of the deportees, nor on its agreement with the United States or whether financial arrangements have been involved.

Detention and Security Risks in Cameroon

While Cameroon has signed the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, it has not ratified the treaty. It has, however, signed and ratified other key conventions which include protections for nationals and non-nationals alike, including the Convention against Torture, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Nevertheless, numerous observers have raised concerns regarding detention conditions in Cameroon, raising credible fears for the deportees. In 2023, the U.S State Department described prison and detention conditions as “harsh and life-threatening,” with researcher Jill Alpes Maybritt noting in 2017 that the Cameroonian penitentiary system does not separate convicted criminals from detainees held in preventive custody, and that “as a result, inmates can easily be subjected to rape, murder or other acts of violence.” Overcrowding is also an issue: according to the World Prison Brief, in 2024 the country’s prisons had an occupancy level of 164.3 percent. Between 2019 and 2021, Human Rights Watch also documented the arbitrary arrest and detention of Cameroonian returnees, noting that they faced inhuman and degrading treatment in detention –including torture, physical and sexual abuse, and assault–as well as “squalid detention conditions with little to no food, medical care, sanitation.”

Cameroon also continues to be gripped by various security crises, including an ongoing conflict in the country’s Anglophone minority regions, as well as persistent threats from Boko Haram and Islamic State-West Africa Province (ISWAP) in the far north. With a population of 1.1 million internally displaced persons, Cameroon is the “most neglected displacement crisis,” according to the Norwegian Refugee Council. In its 2024 report on human rights practices, the U.S State Department itself noted that “significant human rights issues included credible reports of: arbitrary or unlawful killings; torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; arbitrary arrest or detention; … [and] serious abuses in a conflict.”

Until 2025, Cameroonians were given Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in the United States, which protected them from deportation to Cameroon, given the widespread danger faced in their home country. When the Trump administration announced the termination of TPS for Cameroonians in April 2025, many reported fears for their safety if they were forced to return.

“Costly, Wasteful and Poorly Monitored”

The U.S. arrangement with Cameroon is the latest in a string of externalisation deals struck by the Trump Administration–and which, like Cameroon, have often involved countries that fail to abide by human rights norms. As the GDP noted in a submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants in late 2025, the arrangements themselves are also commonly opaque, with the documents pertaining to agreements rarely made public. Often, they have involved large sums of money–although the details are similarly not always clear.

According to a recent report by the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee Minority, up until January 2026 the Trump Administration had spent over $40 million in third country deportations–with $32 million paid directly to five countries (Equatorial Guinea, Rwanda, El Salvador, Eswatini, and Palau) to incentivise them to accept third country deportees. These five countries had received approximately 300 people–250 of whom were sent to El Salvador, leaving 51 sent to the other four countries for a cost of $27.6 million.

Combining payments to foreign governments with estimated flight costs, the report approximates that the U.S has paid $1.1 million for each of the seven persons sent to Rwanda, and $413,333 for each of the 15 sent to Eswatini. With such vast costs, it is clear that these schemes are designed less for operational efficiency than for symbolic deterrence–projecting a hardline posture on irregular migration rather than advancing a coherent or cost-effective removal strategy. As Department of Homeland Security, Tricia McLaughlin, said in August 2025: “If you come to our country illegally and break our laws, you could end up in CECOT, Alligator Alcatraz, Guantanamo Bay, or South Sudan or another third country.”

The report notes particular concern that these funds have been channeled directly (rather than through trusted third-party implementing partners who provide monitoring and oversight) to corrupt and unstable foreign governments with track records of corruption, human rights abuses, and trafficking, with no evidence that the government is monitoring how funds are spent.

“The Administration has pursued these arrangements through opaque negotiations, including with corrupt governments, without meaningful oversight or accountability. Tens of millions of dollars in taxpayer funds have been sent to foreign governments, yet Congress and the public have few details on the terms of these deals, how funds are being used or what the United States is offering in return.”

In November 2025, the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights issued a resolution cautioning against the externalisation of migration governance and urging African States to safeguard the rights and dignity of migrants deported from non-African countries.

Read More:

Human Rights Watch (20 February): Abuses in Cameroon After US Deports Third-Country Nationals

Actu Cameroun (21 February): Expulsions vers le Cameroun – Washington et Yaoundé accusés de violations des droits humains

Committee to Protect Journalists (23 February): Cameroon Police Probe Journalists Investigating Secret US Migrant Deportations, Seize Equipment